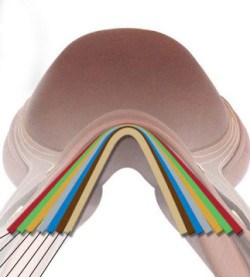

One of the best innovations in the world of saddle making has been the interchangeable gullet plate in the synthetic saddle tree. I mean, there’s no getting away from it, it’s brilliant. With the removal of a few screws, every horse owner can adjust their own saddle in minutes. Easy.

Why so good? Well, they can be fitted to a lot of horses. They can accommodate the changing shape of a growing young horse, as well as seasonal weight gain and loss, or the development of back muscle through training.

Why so good? Well, they can be fitted to a lot of horses. They can accommodate the changing shape of a growing young horse, as well as seasonal weight gain and loss, or the development of back muscle through training.

So what’s my problem with them?

Unfortunately, such saddles are often accompanied by extra inventions,

this time originating in the marketing department.

Before I go on, I must declare an interest here. I fit saddles. What’s more, I fit saddles with interchangeable gullet plates. I’m not going to say which brand, because that’s not what this post is about. I say this simply to demonstrate that I’m not against adjustable saddles.

My problem is very much with the misleading statements that are made in order to sell them, and in particular the notion that these saddles can be adjusted to fit any horse. Not just a single weight-changing or shape-changing horse, or a few horses in the same yard, but any horse.

They can’t. It’s not true. They simply can’t.

Back to the horse’s back

Let there be no doubt that many horses experience a lot of pain from ill-fitting saddles that are too tight, or too wide, at the front of the tree. Most people are familiar with the sight of horses with white hair behind the shoulder blade, and areas of mild to profound muscle wastage.

Let there be no doubt that many horses experience a lot of pain from ill-fitting saddles that are too tight, or too wide, at the front of the tree. Most people are familiar with the sight of horses with white hair behind the shoulder blade, and areas of mild to profound muscle wastage.

The so-called wither profile is incredibly important for this reason. Gaining a correct fit across the gullet (and I mean gullet in the Australian sense – referring to the front of the saddle tree only, rather than the entire channel) is a highly important aspect of saddle fitting.

Yet it isn’t the only aspect. Astonishing as it may seem, horses are 3-dimensional organic structures. Yes! And they have many profiles in that area where the saddle sits.

Think about horses’ backs. The gullet plate matches the profile across the withers. But what about the profile along the withers, as well? Withers have different heights and lengths…

Think about horses’ backs. The gullet plate matches the profile across the withers. But what about the profile along the withers, as well? Withers have different heights and lengths…

There are other profiles, too. There’s along the spine. There’s across the back at the rear of the saddle area, close to the last ribs. All of these profiles have both lengths and angles.

This is one of the reasons why many experts in the world of saddle making and fitting refer to the 9 points of saddle fitting. Several of these points involve the length and angle of the profiles I’ve just mentioned.

Going back a few years, the common view was that there are 5 points. Times have moved on, anatomy and biomechanics are better understood, and saddle design has evolved dramatically to reflect more recent ideas about how a saddle should interact with the horse’s body and movement, as well as the rider’s. And yet…

Going back a few years, the common view was that there are 5 points. Times have moved on, anatomy and biomechanics are better understood, and saddle design has evolved dramatically to reflect more recent ideas about how a saddle should interact with the horse’s body and movement, as well as the rider’s. And yet…

Fitting saddles isn’t like buying a pair of socks

Going by a single measurement might be OK for some things, but it isn’t for saddles. There’s more than one measurement involved, and I’m not just talking about the rider’s seat size. Think again about horses’ backs.

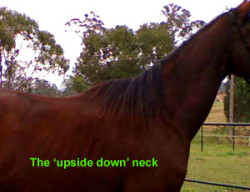

- We have high withers, middling withers and rangy tabletops. High withers can extend way back into the area of the saddle.

- Looking along the spine, we can see dippy backs, straight backs and bumpy backs.

- Looking across the spine, we can spot angular A-frame backs and smooth, flat and pudgy backs.

- It’s easy to spot uphill and downhill backs.

- Not to mention short backs and long backs (or, to be more accurate with saddle fitting, rib cages).

- And spines may have wide spinal processes or narrow ones.

- And how about round rib cages that spring out nearer the spine, or narrow, flat-sided rib cages that drop sharply away, and everything in between?

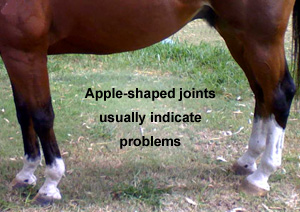

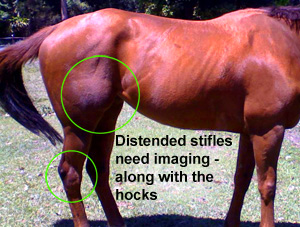

- This is before we even look at damaged backs, uneven shoulders, laterally curved spines, and all manner of physical issues affecting the horse, rider and the saddle in between.

Horses have a combination of these features. Many horses have one or two that can make saddle fitting a bit tricky. Some have combinations that make saddle fitting an utter nightmare.

The saddle’s tree must reflect all those variations. It’s what makes saddle fitting such an interesting challenge, and occasionally a very hard one.

Exclusive posts on Saddle Fit are available on The Horse’s Back Patreon, including The Deep, Deep Pain Caused by a Poor Saddle Fit and The Princess and the Pea… or, the Saddle and the Ding in the Back. Join today and have access to 25 archive posts straight away. Membership from US$ 7.50 per month.

But what about adjusting the flocking?

Well, what about it? Adjusting flocking is the saddle fit version of fine-tuning. It is not changing the overall fit of the saddle.

Adjusting the flocking when the tree is the wrong shape is like (ahem) whistling in the wind.

It’s like adding an extra hole to your belt in an attempt to make a pair of jeans fit, despite the fact that the waist is a size too narrow and the legs 6 inches too short.

Adjusting the flocking only works when the tree is already a fundamentally good fit. The same goes for any flocking substitute, such as risers or wedges inserted into the panels. It is not enough to make a saddle fit the horse, when the tree is the wrong shape.

The message is being massaged

Adjustable gullet plates are now free of the original designer’s patent restrictions and a number of companies are now using them.

As already said, that’s great, providing the saddles are fitted well.

And who determines that? It can be hard to be sure when certain departments continue to make this ongoing, inaccurate claim about their brand of saddles being adjustable to all horses.

It’s marketing at its worst. It’s not just misleading, it’s plain untrue. Worse, it’s willful mis-education that leads horse owners into the mistaken belief that because they have the right gullet plate, then their saddle fits and their horse can’t possibly be in any pain.

It bugs me that people are being misled. It bugs me far more that horses end up being the silent incumbents of a problem with so much potential to lead to back pain. (And I have worked with the results first-hand.)

As I said earlier, when the saddle fits, FANTASTIC. In fact, FANTASTIC with bells on.

And when it doesn’t, it’s the horse who suffers, no matter how many professionals are saying that black is in fact white, and that with the right ‘system’, an adjustable saddle can be made to fit any horse.

It can’t.

June 2019 update: 5 years after publishing this article, I received the following message from the Ruiz Diaz company in Argentina:

“I am part of the team producing Pessoa, PDS and Anky saddles. I just want to let you know that we have been working on our saddles for better fitting on the rest of the body and not only the withers. Thanks for your article once again, it was really nice to read your words and realize that with a wrong concept we have been saying that the x-change system was fitting every horse but there is much more apart the horse withers.”

Questions, thoughts or comments? Join us at The Horse’s Back Facebook group.

A long-term rotated lumbar spine will usually have some fusion between the vertebrae, and/or overriding dorsal processes (the part of the vertebrae you can feel). Fused areas are painful for the horse while they’re happening, and OK once the fusion is complete. But if fusion cracks, it can once more be extremely painful. Many horses compete just fine with some fusion, but if it’s severe, there’ll be problems with flexion, both vertical and lateral.

A long-term rotated lumbar spine will usually have some fusion between the vertebrae, and/or overriding dorsal processes (the part of the vertebrae you can feel). Fused areas are painful for the horse while they’re happening, and OK once the fusion is complete. But if fusion cracks, it can once more be extremely painful. Many horses compete just fine with some fusion, but if it’s severe, there’ll be problems with flexion, both vertical and lateral.