They can lead to scoliosis, spinal arthritis, flexion and straightness problems, saddle fit issues, secondary lameness, hoof problems and soft tissue trauma. So, what on earth are transitional vertebrae, and why haven’t we heard more about them?

To answer the first part of that question, transitional vertebrae are hybrids that appear where one group of vertebrae changes to another. They show mixed features of each group.

They can be found along the spine, where:

- the cervical (neck) meet the thoracic vertebrae,

- the thoracic meet the lumbar vertebrae,

- the lumbar meet the sacral vertebrae (sacrum),

- where the sacrum meets the caudal vertebrae (tail bones).

As for why we’ve not heard much about them, the answer is probably that they’re rarely identified while a horse is alive.

However, they can lead to some very real problems in the living horse due to the asymmetry they cause along the spine – and they’re far more common than you might think.

The affected process or rib can hurt when the horse bends into it, as the abnormal rib/process is literally ‘stabbing’ into soft tissue.”

© All text copyright of the author, Jane Clothier, https://thehorsesback.com.

Thoracic and lumbar transitional vertebrae

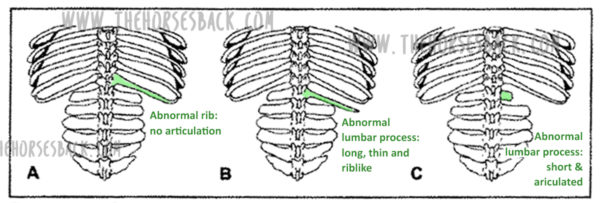

Here are the three main types of variation, as shown in this diagram from one of the few research papers to mention this issue.

Here, we’re going to look at the first two – labeled A and B – which are the most common manifestations.

A ‘process-like rib’ at T18

Labeled ‘A’ in the above diagram, this is a transitional vertebra at T18 (the last thoracic vertebrae) – a rib that thinks it might be a transverse process, lacking an articulation or joint with the vertebral body.

Instead, the process-like rib is solidly attached, meaning there is no independent movement whatsoever. At its end point, it’s joined by costal cartilage to the preceding rib, partially restricting that rib’s movement, too.

This is a problem, as the caudal ribs are not directly attached to the sternum because they need to move more.

The abnormality can be on one or both sides of the vertebra, although single side is most common.

A ‘rib-like process’ at L1

Labeled ‘B’ in the above diagram, this is a transitional vertebra at L1 (the first lumbar vertebrae). Again, it’s usually one-sided, although two sides also occur.

Here, we’re looking at a transverse process that rather than being fairly short, wide and flat, instead extends outwards like a misshapen rib. There’s no articulation with the vertebral body.

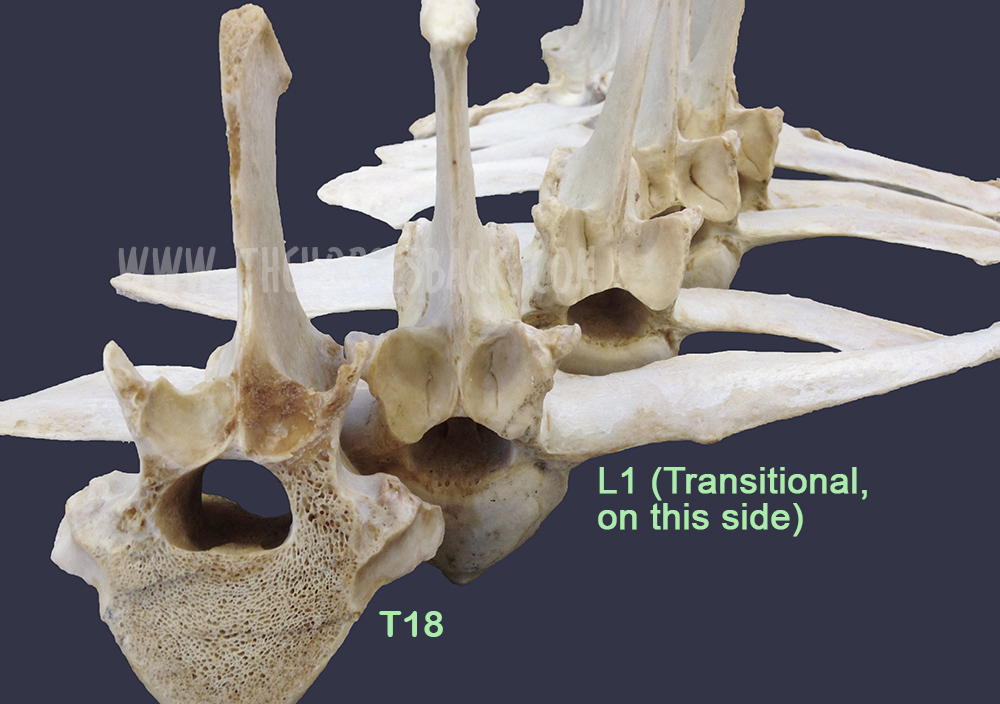

The above image shows an abnormal L1 found in a Quarter Horse mare. This mare was asymmetric throughout her body, and had a history of unsoundness both fore and rear throughout her lifetime.

Effect on the horse

Scoliosis is the major effect of transitional vertebrae. It’s an asymmetry that in these cases can be lifelong and permanent.

I’ve seen it a few times now in skeletons and on horses that have subsequently been euthanized for unrelated reasons – the spine curves in the affected direction, ie. the horse’s ‘short side’ is the same as the abnormal rib/process that is causing restriction.

The above bones were from a TB gelding who was in his late teens. Over his lifetime, the additional pressure on the side of the abnormal L1 had caused greater bone development in the vertebra further forward. In this photo, T18, the last thoracic vertebra, has been cut to show this impact.

Cases are highly individual and the degree of impact depends on how abnormal the vertebra is, plus other factors affecting the horse’s musculoskeletal balance – including tack and riders. However, we can consider the following points.

There can be an obvious localized effect:

- The affected process or rib can hurt when the horse bends into it, as it is literally ‘stabbing’ into soft tissue.

- The attachments of the deep, short muscles involved in segmental stabilization at L1 and T18 are affected, also affecting proprioception and posture.

- The abdominal muscles involved in breathing and flexion during locomotion are restricted over an affected T18.

- The diaphragm inserts onto T18, meaning its function is also affected.

This can affect overall spinal health and biomechanics:

- Scoliosis means that bending to the affected side can be uncomfortable, while bending to the opposite side can be highly limited.

- Achieving straightness may be impossible. Scoliosis can extend through the withers and into the neck.

- Impinging transverse processes and vertebral arthrosis at other vertebral joints further limit movement.

- These restrictions make lifting the back problematic.

And then there can be a host of secondary effects:

- In the heavily pregnant mare, existing discomfort due to a T18 may worsen.

- Achieving saddle fit is difficult on an asymmetric horse with scoliosis.

- Abnormal loading can lead to recurrent lameness and persistent hoof issues.

- Unrelated pathologies can scale up uncontrollably, as the horse cannot compensate effectively.

Take a closer look at the vertebrae featured in this article (Equine Healthworks is my practice page in NSW, Australia – also on Facebook.)

Questions, thoughts or comments? Join us at The Horse’s Back Facebook Group.

Can we spot transitional vertebrae in the living horse?

Yes, sometimes.

As this TB mare (above and below) was unable to maintain weight due to the physical stresses she was experiencing, her rib outline was fairly clear.

In her case, the last rib felt wider and flatter than the other ribs. The space between the rib and the point of hip was also noticeably narrower on the affected side (although this would be true of any horse with scoliosis, it’s a matter of putting the picture together, sign by sign).

There were other reasons for suspicion. Even when all the surrounding tissue was relaxed, there was no ‘spring’ when the rib was palpated with a flat hand. That’s not definitive, but it’s a cause for concern.

Do something that most people never do – stand on a fence or mounting block and take a photo down the horse’s spine, when it’s standing square…”

This veteran grey Arabian, below, is one I’d also consider a suspect. Again, we can see a very obvious protruding last rib on the offside and a lack of straightness. Even with musculoskeletal bodywork and spinal mobilization, the rib remained just as pronounced.

Incidentally, I’ve also worked on this horse’s offspring, and the younger horse has the same profile to the ribs, on the same side, accompanied by a history of inexplicable back pain – and lack of straightness.

Note: It’s important to eliminate other causes first, as horses will often have this appearance at the last rib, without it being caused by a transitional vertebra. What’s happening is that the rib is protruding because the vertebra is immobilised in a rotated position. When chiropractic, osteopathy or bodywork restores mobility to the spine, the rib returns to its normal position.

Ongoing hoof issues

In the bay TB mare, spinal asymmetry (scoliosis, with bend to the right) had led to excessive loading of the near fore. This was no doubt compounded by constantly training and racing in a clockwise direction, plus the classic long toe/low heel frequently found in ex-racehorses.

As a result, her near fore had constant hoof wall separation, bacterial infection (seedy toe / white line disease) and a deep P3 problem that would never come right.

Here’s the hoof capsule and P3. Yes, the poor girl suffered, despite extensive efforts to reconstruct that hoof.

Patreon members can view videos of this mare and further photos. Go to: www.patreon.com/thehorsesback for more details.

The TB gelding mentioned earlier also had chronic issues in the opposing fore hoof, with wall separation, damage to P3 and evidence of earlier laminitis.

How many horses are affected?

Who knows? The study mentioned earlier (Haussler et al, 1997) found that 22% of Thoroughbreds examined at necropsy, having died or been euthanized at the racetrack, had thoracolumbar transitional vertebrae.

To date, I’ve come across 3 in above-ground skeletons (2 x T18, 1 x L1), plus one in a horse later euthanized (1 x T18). These were TBs and Australian Stock Horses.

And as mentioned, I’ve suspected the T18 issue here and there amongst clients’ horses.

Although found mostly in Thoroughbreds, transitional vertebrae are seen across a range of breeds. And certainly, with equine dissection having taken off in quite a big way in the equine care industry, more and more of these anomalies are being observed.

Questions, thoughts or comments? Join us at The Horse’s Back Facebook Group.

Should we be concerned?

The answer is, inevitably, both yes and no.

On the positive side, if the numbers harbouring this problem are as high as it seems, we have to assume that many horses are coping just fine.

For as with any musculoskeletal anomaly, horses can compensate very well.

However, when another problem is added to the mix, things can head south very quickly indeed.

And it can all happen without us ever knowing that a skeletal anomaly is an underlying factor. When this happens, owners often have a lot of unanswered questions about their horses – and often large vets bills.

It’s the TB or TB-derived breed horse that is most likely to present this (although not exclusively). If you’re buying one and you view a horse with an obvious T18 that really stands out, you might want to get that checked.

At the very least, do something that most people never do – stand on a fence or mounting block and take a photo down the horse’s spine, when it’s standing square or close to square.

If there’s a clear scoliosis along the spine, be cautious (this is a good rule of thumb anyway, no matter what the cause is). If you see an overly pronounced rib on the concave side, be doubly cautious.

And if you believe your horse may have one, the answer is the same as always: be aware, take a 360 degree approach in ensuring that hooves, tack, training and riding are as good as they can be, and your horse will have the best possible chance of functioning well without cause for concern.

Fantastic. I know from human dissection, studying bones and xrays, the ridiculous amount of anomaly there is. I have some myself, along with some other asymmetries that drove me into bodywork and functional movement. I can testify both that they are problematic, as well as how imperative proper maintenance and conditioning, strength and mobility are for my well being. It’s doubly interesting in light of the current focus on a variety of different straightness trainings. But as stated, probably a lot of horses are doing just fine. On the flip side it supports that many behavior problems are actually pain problems. So thanks for sharing this.

Thank you. Isn’t it amazing how much insight we gain through our own conditions and experiences? I myself am not straight and my experiences in fitness classes, particularly with weights, give me plenty of food for thought about what we ask of our horses, and what feelings their restriction might cause when being asked to move and weight bear at the same time.

A very interesting article. We clearly need as much knowledge about the kinds of pain a horse might have do to spinal problems. I will be diligently checking my horses for this anomaly. One comment though. I rode on the race track for years. On the farms the babies are galloped in both directions, same amount each way. They aren’t as one sided as people think. Racehorses spend just about the same amount of time on each lead, and on a big track, more time on the right lead than the left.

Thank you for your response! It’s great that your young TBs are on farms being raced in both directions. Here in Australia, that frequently isn’t the case. Many horses live in stables right next to the racetrack (less with the big name trainers, but definitely with the regional trainers) and are subject to that one-way life. Sadly, that was certainly the case with the mare featured in this post.

Excellent article and another way-too-common issue we all have to take into consideration! Have had a couple and the worst correlated very clearly to palpation findings when looking back. I never confirmed whether my Ollie actually had one, but managed it as such – I was constantly trying to create space through the right flank with MFR or the tension would snowball badly, and I ended up putting him in a 16.5″ saddle even with his long back.

My messed up ribs are acquired, not congenital, but iliocostal impingenent is not fun to live with, and nor is a dislocated rib that floats around and stabs you randomly and excruciatingly. For what it’s worth though, mindful movement helps keep the fascia straitjacket at bay and this seems to be the case for some suspect horses I’ve worked with too, if within their limits.

Question is, what will it take to have full-body CT available to screen for all these anomalies on a regular basis so we can work with what is there more effectively in horses that are reasonably functional?!

Thanks, Cat. I couldn’t agree more about the full body CT scan, along with the x-ray glasses!

Any displaced rib can feel awful, even – oddly – when it’s not actually painful. Add pain and the nervous system must be screaming that the body’s protective cage is at risk. I feel that the worst cases, like the mare in the article, would probably have done OK in nature, but add riders, tack, unsympathetic training and riding – there’s only so much the compromised structure can cope with. That mare received the best of *everything*, at least in our terms on the bodywork/saddle-fit/hoofcare front, but sadly it all came too late.

Yes, and have it (CT Scan) be affordable to horse owners.

Thanks

Brilliant article. Makes me think more about what might be causing training and soundness issues. Thank you.

Thank you 🙂

Timely and very much appreciated. Thank you for the clear explanations and all of the great photography. A keeper!

Thank you. I did enjoy creating these photos, positioning them to truly show the extent of the asymmetry and the impact they might have on the tissues.

Do you think inbreeding is the cause? So many horses in different breeds have been “line bred” – so could this distortion be a product of that? THAT would be another good reason to stop that practice. Or the modern thing that happens too often of keeping mares on short to no grass and hand fed to try and replace nature’s bounty? So that their mineral balance in utero and while they’re growing is off? Or does the type of work a horse does cause it or make it worse? i.e. working WITHOUT the elevated back that enables them to carry a rider comfortably? (Which sadly is high 90 something percent of all ridden horses.) Or all of the above? Gee it would be good to know the breeding history and feeding history and working history of these skeletons!

Most likely inherited, and yes line breeding within certain pedigrees would help to perpetuate the problem. It’s a congenital malformation, so there at birth, regardless of the mare’s nutritional status or later ridden practice. I 100% agree that it’s yet another problem that can best be managed by correct self-carriage and preparation for ridden work, although any correction will be dictated by the extent of the malformed rib/process.

Yes ! Kissing spine, stenosis, has a gene that can be found in the Raise A Native line has been linked to this.

I’m interested in this genetic factor – can you point me to any more information, please?

My mare has Raise A Native in her lineage. I’ve always attributed her poor feet to Mr. Prospector, but for the first time I’m beginning to think she has scoliosis. As she’s as she’s aged I’ve had to change saddles and am still struggling with a good fit. No one, vet, chiropractor, saddle fitter, massage therapist, farrier, or other professional or riding colleague has ever suggested this, but I decided to do an online saddle fit evaluation for my own education, and sadly, it’s the first time I’ve ever photographed her from above (albeit from the back). She’s always been concave right so I’ve engaged in a lot of straightness training, but based on what I’m seeing now, I’ve asked the vet for her opinion on scoliosis. She is in Etalon’s ongoing kissing spine DNA study, but as a non-kissing spine sample. It will be interesting to find out if the same genes identified for kissing spine turn out to be implicated in other spinal abnormalities.

I trim a horse that looks like he is missing a rib. I have pics of his side. The right shoulder is completely under muscled. I am wondering if this is his issue? Any way I can get these pics to you to find out?

Hi Kelly, it’s very unlikely that this will show up in photos. The ones I’ve presented have the benefit of hindsight and/or an awful lot of assessment. However, you could be describing a condition called Sweeney there. Have you ruled that out?

I just looked up Sweeney and that isn’t what I have a pic of. The space is mid back. The top line is gone and you can see the rib cage on this side. The other side of the horse looks normal.

Thank you for sharing this article!

Have you ever seen a horse that had bilateral transitional processes?

I have a warmblood dressage mare that I have been working on (I’m an equine body worker) for two years now, every two weeks. She is a beautiful mover and very capable through most of her work. She had one baby before she started training, but other than that her history is clean. She has always had this weird muscle bunching bilaterally in front of her hip joint…I would say over ribs T16-18. It doesn’t matter as much as I wrk with the tissue and surrounding areas it never goes away…she does not allow me to work on her inner groin/thigh muscles especially her psoas. Her training has recently started to dimish. She get chiropractic every 6-8 weeks and I work on her every two weeks. Her thoracic spinal column feels notchy almost to where I would be concerned of pre-kissing.

We have stopped working on her and she is going for a nuclear scan at the end of the month, but after reading this article I wonder if she could have transitional processes on both sides causing all of the above?

I could get pictures in two weeks to share but thought it wouldn’t hurt to ask now if you had come across any bilateral cases?

Thank you.

Jackie

Hi Jackie,

Not personally, but I know people who have come across them. I’ve suspected one or two, but it’s so hard to get confirmation! In their mild form, these can cause little problem, but when more extreme, there are definitely other problems through the spine. I’ll be very interested to hear what the outcome of the scinitigraphy is in the mare you know. Please do post back!

As for photos, there’s one here, on one of my Patreon posts https://www.patreon.com/posts/18676825 (photo credit rodnikkel.com – it’s part of a skeleton that Denise Nikkel reconstructed).

Jane

Jane,

Thank you for your response and the link to the bilateral photo, that is really interesting. So the mare I mentioned above went for her nuclear scan and after going over her thoracic and lumbar spine there wasn’t a lot going on to have a definitive diagnosis…the vets decided to scan her neck and we found her C6 to be at a very bad angle and they diagnosed her with Wobblers…even though she is completely asymptomatic. They have recommended retiring her from riding as it is dangerous for both horse and rider. Now the owner has to decide if she wants to breed or not. The mare if lovely, but there is a chance that her C6 dysfunction is hereditary. Anyways, thats the update…we are all sad that she has to be retired, but also relieved that we were able to “find something” after such a long time of searching. Thanks again for your info and support.

Jackie

I’m guessing that you’ve considered the congenital C6-C7 issues also covered on this site? It’s worth establishing whether she has that, before deciding on whether to breed from her… it only worsens with age. How old is the mare? I’ve come across horses that are very bunched up behind from trying to avoid loading forwards onto the affected side.

I’m wondering if surgical removal is an option? It would seem that if they can help alleviate kissing spine that there may be a surgical procedure to cut were shorten or renews this anomaly.