This follow-up to ‘The Disturbing Truth About Neck Threadworms and your Itchy Horse’ discusses how to manage the parasites, once you know your horse has them.

The original article was aimed at my Australian bodywork clients here in NSW, yet it quickly worked its way through other networks – I haven’t a clue what or where, but it started running and it’s still running today.

All text (c) Jane Clothier, https://thehorsesback.com No reproduction without permission. Thanks!

Astonishingly, five years later, it’s been read by over 500,000 people in nearly every country in the world.

I make no claim to be the first to write about neck threadworms. For making it a more widely known issue, the forum members of The Chronicle of the Horse website must take credit (and I recommend anyone with specific questions about their horse to head over there).

I guess my post succeeded in bringing the available information together in one place – in that it simply reflected my own experience of researching the subject on behalf of my newly itchy, increasingly unhappy horse.

‘The Disturbing Truth’ has certainly offered a possible answer to many owners whose horses are besieged by the living hell that is variously known as Sweet Itch, Summer Itch, or Queensland Itch.

That’s because in a certain percentage of cases – not in all of them – the cause is onchercerciasis, a hypersensitive reaction to the larvae of the Onchercerca cervicalis parasite.

Ignore the nay-sayers – it’s an international battle

One thing that’s become really, really clear from responses to the first article is that onchercerciasis is a problem for horses worldwide. It’s obviously worse in some climatic areas than others, but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist in cooler zones.

Reading the comments triggered by the article tells us all we need to know. Horses travel within countries and internationally – the larvae can then be transmitted to new host horses in the destination region, providing there are enough local culicoid flies to transmit them.

As another reader pointed out, warmer and wetter winter and summers are giving the flies a better hit at it than ever before.

Research has shown the presence of neck threadworms in horses in such non-tropical countries as Canada, the UK and Poland. In fact, the UK research was conducted in the early 1900s, showing that air transport of horses has little to do with it and that this parasite has been in cooler climes for a long time.

Dragging neck threadworms into the daylight

The comments at the bottom of ‘The Disturbing Truth’ are illuminating. Some people have battled their horses’ itch, often so bad that it prevents their horses from being ridden, for a decade or more.

They have struggled with different diagnoses, with various medications, with investigations into suspected colon disorders and testing for allergen sensitivities, all to no avail. Everyone involved certainly meant well, but the problem still remained.

Astonishingly, more than one person has previously mentioned neck threadworms to their vet, only to have it dismissed out of hand, because “that’s not a problem around here”.

Despite this, some of those same horse owners have started treating their horses and are already some way down the road to reducing the larval population and are resolving the issue. Some are seeing manes grow back on their horses for the first time in years.

This isn’t to say that all itching is caused by the larval stages of Onchocerca cervicalis. I don’t want to be grandiose about this. But it’s certainly affecting enough horses for it to be worth ruling out. For the price of a couple of tubes of ivermectin wormer, why on earth not do just that?

It’s baffling that this problem has ceased being common knowledge and so often slips under the radar. It’s true that the companies producing wormers certainly know about neck threadworms, but quite naturally focus on promoting their products’ effectiveness against far more serious gastrointestinal worms.

(And let’s be honest, many horse owners feel distrust towards drugs companies, whether involved in human or veterinary medicine.)

Even so, in regions such as the Australian tropical and subtropical zones, you’d think there’d be a bit more awareness, wouldn’t you? But then perhaps we’ve all been so hung up on Queensland Itch, we’ve been unable to see the wood for the gumtrees.

[Article continues after advert.]

Down to business: How to win at worming

With your initial burst of worming, either on a fortnightly or monthly basis, single or double dose (as described in ‘The Disturbing Truth’), you’ll have established that your horse does indeed have neck threadworms.

Using ivermectin, you’ll have seen a temporary worsening of the problem and, possibly, the increased itching and/or eruption of pus-filled lumps in the mane.

Moving on from that point , it’s important that you establish a strategy for dealing with the ongoing presence of the neck threadworms in future months and years.

Regretfully, when I say ‘win at worming’, what I actually mean is ‘win at managing the worms’. As we know, you can’t kill off the adults, only the microfilariae. Hence you can only strive to bring it all under control.

That’s why tackling neck threadworms in your horse is a numbers game. It’s safe to assume that most horses can deal with a relatively small number of microfilariae, so it follows that the more you can bring those numbers down – and keep them down – the more likely it is that your horse will be able to deal them without experiencing hypersensitivity.

In other words, the itching will ease.

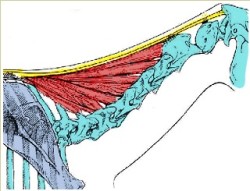

Just to repeat: you can’t bump off the adults. Once they’re in your horse’s nuchal ligament, they’re there to stay for 10 years or more. And then even when they die, they remain present, entombed in a small calcified lump in the ligament.

You can see one in the picture on the right. ‘M’ marks the center of a lump nearly 2x4cm in a veteran horse’s nuchal ligament.

How frequently should you worm?

At different times of the year, the microfilariae being introduced to your horse will vary in numbers, depending on the level of culicoid flies around. This means that with evenly spaced wormings, you’re going to have different results at different times.

As the warmer months are going to see faster increases of the population, it makes sense to worm more frequently in Spring and Summer. The microfilariae are picked up from a horse by the biting fly, after which they develop in the fly for 15-21 days (research seems to differ on this point).

The flies are the vectors that take the larvae through an additional life stage. After this time period has lapsed, they deposit them back into a horse. This is going to happen faster with horses that live in herds within a kilometer or so of standing water.

- Some owners feel that monthly worming during Spring and Summer is sufficient to interrupt the pre-adult lifecycle. Check with your equine vet if you’re not sure (although one reader’s vet suggested worming at 6-monthly intervals, for some mysterious reason).

- Once the microfilariae numbers are down, possibly after the first year, some owners come down to 6-weekly and 8-weekly wormings.

- Others prefer to leave the horse from mid-Autumn until mid-Spring, following only a ‘normal’ worming schedule during this time, before worming more frequently during the fly season.

In the end, it’s a matter of individual choice. All you can do is observe your horse and keep at it until you see a significantly reduced reaction in terms of itching.

The longer your horse has been living with neck threadworms, the longer it’s likely to take. And the more tropical and humid your regional climate, the more biting flies there are going to be. Even so, you might be pleasantly surprised by the speed of the positive change.

Include gastrointestinal worming in your plan

Once you’ve used an ivermectin wormer to identify the presence of neck threadworms in your horse (see ‘The Disturbing Truth‘), it’s sensible to also worm intermittently with moxidectin, found in Quest/Equest. The reason is that this is the only wormer to hit Onchocerca microfilariae AND encysted small strongyles.

While neck threadworms can make life highly unpleasant for your horse, encysted small strongyles can kill him or her if they suddenly erupt.

They would have to build up to a high level first, but if your horse has been malnourished before coming to you, or is a rescue horse, or if you’ve only used ‘natural’ wormers for some years, you have the perfect conditions for such an event.

The best approach is to address the intestinal worms before moving onto the neck threadworms. So if it’s unlikely your horse has had Quest/Equest or Panacur for some years, use one of these first.

In my region, Strategy is also valuable in addressing pinworms, which are resistant to many other products.

Support your horse’s intestinal tract

Worming for neck threadworms is always going to be a necessary evil. None of us would wish to be following such a rigorous worming schedule if we had the option, so we must do our best to mitigate any negative effects.

If you’re following a heavy worming schedule, you should also be supporting your horse’s gut, which is going to be taking a chemical hammering.

The best place to start is with probiotics, either added to the feed or administered through a plunger tube (although your horse may be a little off plungers at the moment…).

The reason for using a probiotic, which is essentially a supply of beneficial flora for the hind gut, is that the existing ‘beneficial bacteria’ will have been reduced by the wormer. It’s then more likely that pathogens (‘bad bacteria’) will proliferate, potentially leading to intestinal inflammation and diarrhoea.

This is not only uncomfortable and painful for your horse, but the affected digestive processes will reduce nutritional uptake, which in turn leads to an impaired immune system.

And what happens with an impaired immune system? The horse will be itchier.

Using probiotics means that in supporting your horse’s intestinal function during worming, you will also be supporting your horse’s immune system. It’s a double-win .

You can also help to restore damaged mucosal lining. Various plant sources are ‘mucilages’, meaning that when mixed with water, they form a slippery substance that lines and soothes the intestine. You can consider using aloe vera juice, slippery elm, marshmallow root, liquorice root and chia seeds.

Itching elsewhere on the body

Some owners are saying that their horses, which have had all the signs of neck threadworms, have also started itching on the tail head and along the back. This doesn’t fit with the usual oOnchocerciasis locations of head, neck, chest and ventral areas, and could be due to:

- Pinworms, which lay eggs around the anus and cause itching of the tail head,

- The horse reacting to dying microfilariae previously delivered by culicoid flies biting in ‘atypical’ areas of the body (it’s interesting to note that bite locations may vary according to the particular species of fly, which differ from country to country),

- The horse reacting to the saliva of all culicoid flies, having become hypersensitive to microfilariae that have entered their current life stage within the flies’ saliva. In other words, the horse has developed the Itch.

It’s worth noting that there are two different types of Onchocerca worms also affecting horses and donkeys, and that these cause problems in other areas of the body.

- Itching on the legs can be due to Onchocerca reticulata, as the adult worms are found in the connective tissue of the flexor tendons and suspensory ligament of the fetlock, mostly in the forelimbs.

- In donkeys, Onchocerca raillieti are also found in the nuchal ligament but also, nastily, in subcutaneous cysts on the penis and in the perimuscular connective tissue.

Can neck threadworms lead to the dreaded ‘Itch’?

Now, this is where things get a bit curly. Once your horse has started reacting to Onchocerca microfilariae, they may develop The Itch – aka Queensland, Summer or Sweet Itch (take your pick).

If their system is reacting to the microscopic larvae carried in saliva, why not react to the saliva itself? The immune system is nothing if not intelligent: it learns and it acts on the information it receives.

I’ll be honest here. I’ve not read any research into this, but hooray for Dr Carl Eden BVM&S MRCVS of Virbac, who writes:

Internal parasites such as Onchocerca cervicalis… may also cause pruritus and in the case of O. cervicalis, its involvement in cases of Queensland itch must not be underestimated.

Let’s look at this for a moment.

The Itch is a clinical syndrome, being a hypersensitivity to certain allergens. When the allergen is the saliva of the culicoid flies, the outcome is an inflammatory response.

This in turn leads to a pruritic (itching) skin condition. We’ve all seen its awful progression from hair loss, bumps and wheals, to alopecia, crusting, broken skin and worse.

So I’m speculating here: some of the horses with neck threadworm symptoms develop the Itch as they develop a heightening, acute sensitivity.

The thing is, whether this supposition is right or wrong, you can do no wrong by managing your horse as if it has both neck threadworms and the Itch.

Managing the itching side of neck threadworms

While you’re working on reducing the microfilariae numbers, there’s plenty you can do to make your horse more comfortable. There’s nothing worse than seeing your horse breaking his or her skin while rubbing an itch that won’t ease, whether it’s caused by neck threadworms alone, by the parasite and a developing itch problem, or by the parasite and a pre-existing itch problem.

I’m not going to go into lots of detail as to what you can do, but here, in no particular order, is a starter list.

- At the heavier end, a short course of glucocorticoid therapy (ie, steroids) will reduce the inflammatory response. Some owners have used oral prednisolone – Preddy®-granules – to support their horses during the initial stages of ivermectin worming. It’s not good for pregnant mares, suspected or actual laminitics (steroids can trigger an onset) and horses with internal issues.

- Antihistamine preparations work on the chemical response, but may lead to occasional behavioral changes or even have a sedative effect.

There are changes you can make to your horses diet and nutrition:

- Supplementing your horse’s diet with Essential Fatty Acid (EFA) – Omega 3s – has been shown to reduce insect hypersensitivity. This can be a shop-bought product, or cold pressed linseed oil, or cod liver oil added to the feed.

- Improving mineral supplementation helps to boost the immune system. This doesn’t mean using an off-the-shelf standard product, although that is better than none. Ideally, identify the deficiencies or imbalances in your horse’s forage and diet, and then supplement accordingly.

- Some people are using a combination of chondroitin sulphate, spirulina, and ground linseed (flax) in the daily diet, with some success.

- Probiotics also help to boost the immune system by improving gut function, as we saw earlier.

There are also measures you can take to keep the culicoid flies away from your horse in the first place:

-

A fly rug keeps the carriers, the culicoid flies, away from the horse (c) sweetitchtreatments blog External and topical protection can help to keep the culicoid flies at bay: fly rugs, wipe-on insecticides, and oil-based creams and lotions, especially those containing camphor, menthol or thymol, act as barriers while providing relief and repelling flies.

- If you stable your horse, try to do so between 4pm and 8am, when the biting flies are most active in subtropical and tropical zones. Fans will help circulate air and discourage flies, while mosquito netting on windows will also help.

- Bathing in dermatological shampoos containing chlorhexidine gluconate bring relief while working against localized bacterial infection.

Do it your way: it’s an individual fight

Ultimately, the line you take when tackling neck threadworms in your horse is going to be an individual one.

You’ll be taking into account the severity of your horse’s reaction to the microfilariae, the duration of the problem, and the intensity of the fly presence in your area. And in managing the itching side, different treatments will work with different horses.

Let’s not forget, there’s also the matter for what you can do in practical terms – eg, if you’re never home from work before 6pm, you’ll be unable to stable your horse from 4pm every day.

And then there’s what you can afford to do on a financial level, especially if you have multiple horses affected (one reader of ‘The Disturbing Truth’ had four).

Please feel free to add your comments and share experiences below. We’re all learning and the contributions are fantastic. Meanwhile, if you’re after specific advice for your individual horse, I recommend talking to the guys over at the Chronicle of the Horse forum.

Queensland Itch, Dr Carl Eden BVM&S MRCVS

Studies on Onchocerca cervicalis Railliet and Henry 1910: I. Onchocerca cervicalis in British Horses* Philip S. Mellora1 p1 , J Helminthol. 1973;47(1):97-110.

Prevalence of Onchocerca cervicalis in equids in the Gulf Coast region. Klei TR, Torbert B, Chapman MR, Foil L. 1984 Aug;45(8):1646-7.

Questions, thoughts or comments? Join us at The Horse’s Back Facebook group.