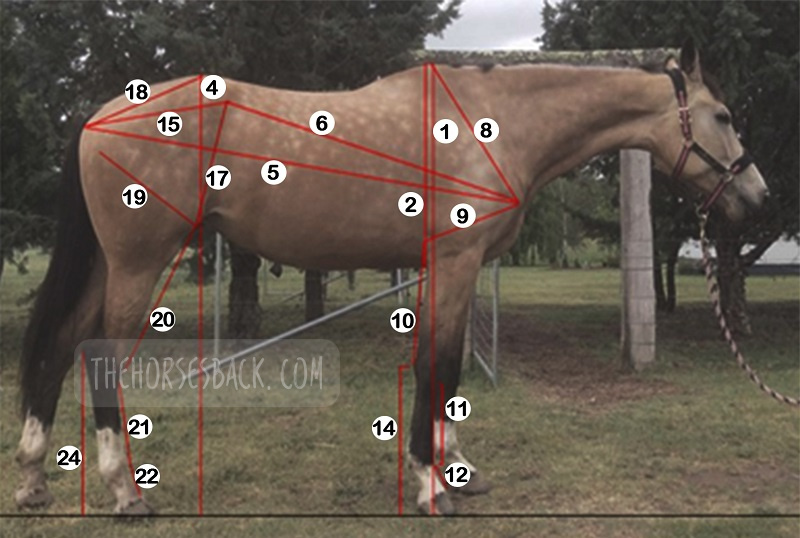

Are certain saddle fit problems related to conformation in Quarter Horses?

My goal with this article is to help you look at your Quarter Horse’s body and, if you see these conformation points, know what common saddle fit problems to check for.

Not all horses in the breed are the same shape, for there are many variations in individual conformation and posture – and there are just as many variations in saddles. The subject would fill many books.

This post is for horse owners who, like many of my clients, simply want to know where to start.

The Quarter Horse and saddle fit problems

The conformational points that feed into many Quarter Horse’s saddle fit issues are:

- Heavy shoulders

- Low withers

- Wide flat back with rounded ribcage

- Downhill conformation

- ‘Curvy’ topline

Some horses have one or two of these, some have all. Some may have none.

So, without further ado, here are the problems they can lead to if not taken into account during saddle fitting.

And by the way, if your Paint or Appaloosa (or any breed of horse) has the same type of conformation, then this may help you too.

1. Low withers and wide back with rounded ribcage

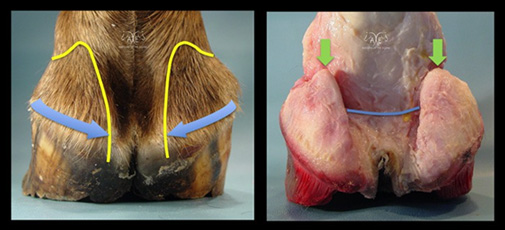

Many Quarter Horses have broad ‘table top’ backs, with round ribcages and sometimes, but not always, with low withers that widen into solid shoulders.

These horses need wide trees with contours that match the back. With flush contact along the underside of the tree, weight is distributed evenly and the saddle is more stable.

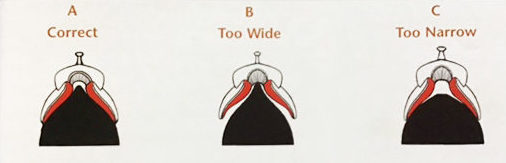

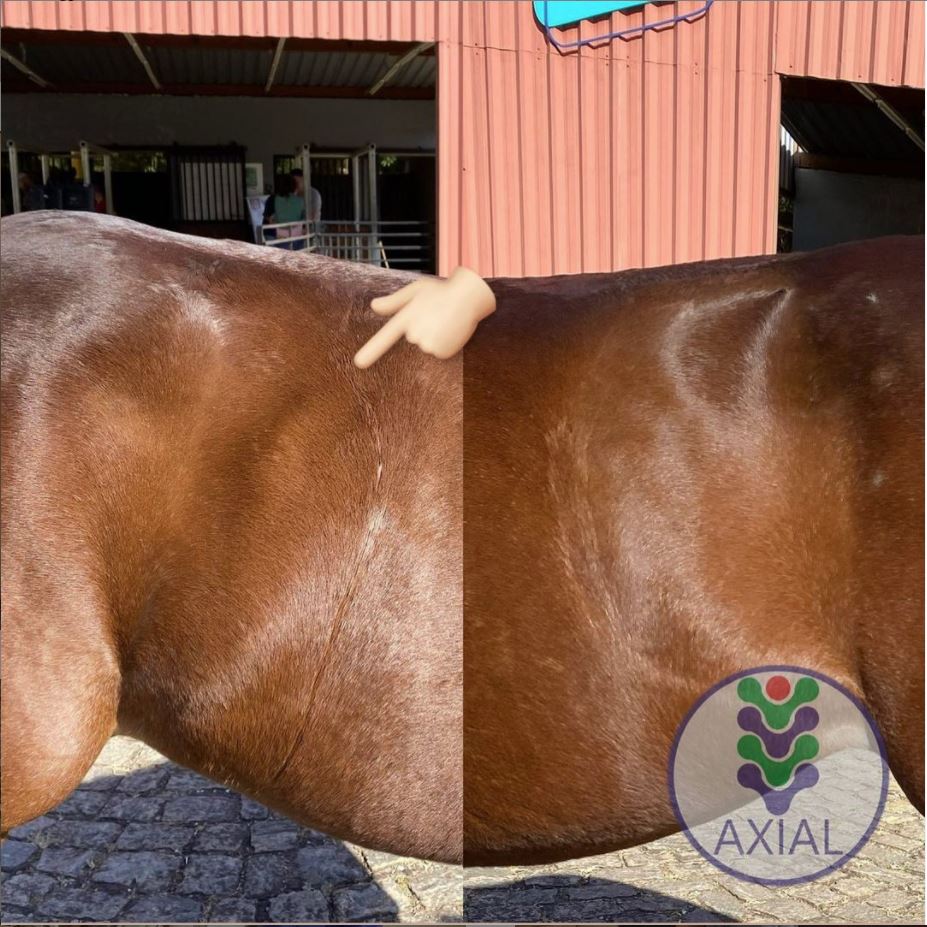

What often happens is that the saddle is large enough to go round the horse, but it doesn’t match the contours of the horse’s back. If too wide at the front, it may fall forward and ‘nosedive’ (that’s not an official saddle fitting term, but hey it’s descriptive). The upper part of the pommel or fork creates pressure, leading to dropped muscle tone and white patches.

If the saddle is too narrow for that broad back and shoulders, it perches on top, and may also be pinching at the lower points of the tree or fork.

Whether because it’s too wide or too narrow, the saddle that creates pressure in the wither pockets can cause hollowing and/or white patches or white flecking.

And when there’s relatively little contact between the tree and the horse, the saddle is also unstable. If perched on top, it can very easily roll to one side or shift around as the horse moves. Likewise if it’s too wide.

2. Large, well-muscled shoulders

Quarter Horse shoulders are often large, deep and powerful. If the saddle is too narrow at the front, such shoulders may lift it during movement. The saddle is rocked backwards and this creates pressure under the rear of the saddle. When ridden, the rider’s weight is now concentrated at the back of the seat, adding to the problem.

The narrow saddle may also bridge. This is when contact under the center of the saddle (lengthwise) is reduced or even entirely absent. As a result, there will then be four areas of pressure: two at the front and two at the back, on either side of the horse.

With restriction at the front, the horse may have raised, overdeveloped muscles in the lumbar region, behind the saddle area. These may be visually obvious if there’s also weak musculature in front.

3. Downhill conformation

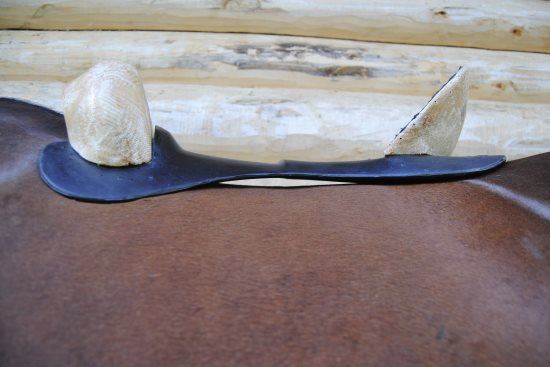

It’s quite common to see Quarter Horses with a downhill conformation. They may be long through the back, with the lumbar spine sweeping up to the croup. The back often also has a deep curve through the saddle area.

This does not mean the horse has the back for a long saddle – it’s often quite the opposite, as these horses may need a shorter saddle to prevent bridging. A saddle may also need a more curved profile along the length of the tree to match contours of the back, while still having sufficient width to go around those shoulders.

The upwards sweep creates strong contact at the back of the saddle. With each hind step, the saddle is shifted forwards, especially if it extends over the lumbar muscles.

Sometimes, the lumbar spine becomes ramrod straight between the back of the saddle and the croup. This is caused by the horse’s efforts to both carry weight and stabilize it by bracing upwards – while moving, as asked.

When ridden, the horse will often step short behind. At halt, it may consistently park the hind feet out behind.

Not surprisingly, in movement, the saddle is pushed forwards due to the high hindquarter action, as well as the forces of gravity. The shoulders can then become restricted, with hollowing in the wither ‘pockets’ and tense muscles across the shoulder itself.

The horse may also drop through the sternum – this brings the line of the chest down, while the pectoral muscles bulge forwards as they work to stabilize the body.

The horse’s neck may be somewhat ‘upside down’ as compensates for the downward pressure while keeping its head elevated. This is compounded if the horse’s neck is already set low. Tight muscles become visible along the upper line of its neck, or there is a general lack of muscle development.

If the rider is also sat well back, even more pressure is created at the back of the saddle.

Useful saddle fitting resources

This article introduces the problems, so what about solutions?

The following resources provide more information on getting your saddle fit right (I’ll add more soon!)

Western Saddle Fit – The Basics 67-minute video on DVD or Vimeo streaming from Rod and Denise Nikkel

Western Saddle Fit: Well Beyond the Basics 6 hours for equine professionals from Rod and Denise Nikkel

The Horse’s Pain-Free Back and Saddle-Fit Book eBook from Joyce Harman DVM

The Western Horse’s Pain-Free Back and Saddle-Fit Book Soundness and comfort with back analysis and correct use of saddles and pads, from Joyce Harman DVM

Saddlefit4Life YouTube channel presents numerous educational videos, from Jochen Schleese of Schleese Saddlery.

Here are abstracts, downloads and links for my research into the ongoing effects or premature or dysmature birth in horses.

Here are abstracts, downloads and links for my research into the ongoing effects or premature or dysmature birth in horses. Breeding horses can be a financially and emotionally expensive undertaking, particularly when a foal is born prematurely, or full term but dysmature, showing signs normally associated with prematurity. In humans, a syndrome of gestational immaturity is now emerging, with associated long-term sequelae, including metabolic syndrome, growth abnormalities and behavioural problems.

Breeding horses can be a financially and emotionally expensive undertaking, particularly when a foal is born prematurely, or full term but dysmature, showing signs normally associated with prematurity. In humans, a syndrome of gestational immaturity is now emerging, with associated long-term sequelae, including metabolic syndrome, growth abnormalities and behavioural problems. Clear definitions of ‘normal’ equine gestation length (GL) are elusive, with GL being subject to a considerable number of internal and external variables that have confounded interpretation and estimation of GL for over 50 years. Consequently, the mean GL of 340 days first established by Rossdale in 1967 for Thoroughbred horses in northern Europe continues to be the benchmark value referenced by veterinarians, breeders and researchers worldwide. Application of a 95% confidence limit to reported GL range values indicates a possible connection between geographic location and GL.

Clear definitions of ‘normal’ equine gestation length (GL) are elusive, with GL being subject to a considerable number of internal and external variables that have confounded interpretation and estimation of GL for over 50 years. Consequently, the mean GL of 340 days first established by Rossdale in 1967 for Thoroughbred horses in northern Europe continues to be the benchmark value referenced by veterinarians, breeders and researchers worldwide. Application of a 95% confidence limit to reported GL range values indicates a possible connection between geographic location and GL. Chronic musculoskeletal pathologies are common in horses, however, identifying related effects can be challenging. This study tested the hypothesis that movement sensors and analgesics could be used in combination to confirm the presence of restrictive pathologies by assessing lying time. Four horses presenting a range of angular limb deformities (ALDs) and four non-affected controls were used.

Chronic musculoskeletal pathologies are common in horses, however, identifying related effects can be challenging. This study tested the hypothesis that movement sensors and analgesics could be used in combination to confirm the presence of restrictive pathologies by assessing lying time. Four horses presenting a range of angular limb deformities (ALDs) and four non-affected controls were used. The long-term effects of gestational immaturity in the premature (defined as < 320 days gestation) and dysmature (normal term but showing some signs of prematurity) foal have not been thoroughly investigated. Studies have reported that a high percentage of gestationally immature foals with related orthopedic issues such as incomplete ossification may fail to fulfill their intended athletic purpose, particularly in Thoroughbred racing. In humans, premature birth is associated with shorter stature at maturity and variations in anatomical ratios, linked to alterations in metabolism and timing of physeal closure in the long bones.

The long-term effects of gestational immaturity in the premature (defined as < 320 days gestation) and dysmature (normal term but showing some signs of prematurity) foal have not been thoroughly investigated. Studies have reported that a high percentage of gestationally immature foals with related orthopedic issues such as incomplete ossification may fail to fulfill their intended athletic purpose, particularly in Thoroughbred racing. In humans, premature birth is associated with shorter stature at maturity and variations in anatomical ratios, linked to alterations in metabolism and timing of physeal closure in the long bones.

Meet Dr Brunna Fonseca, Associate Professor, educator and specialist in equine orthopedics, focusing on the spine and nervous system. She’s based in S

Meet Dr Brunna Fonseca, Associate Professor, educator and specialist in equine orthopedics, focusing on the spine and nervous system. She’s based in S

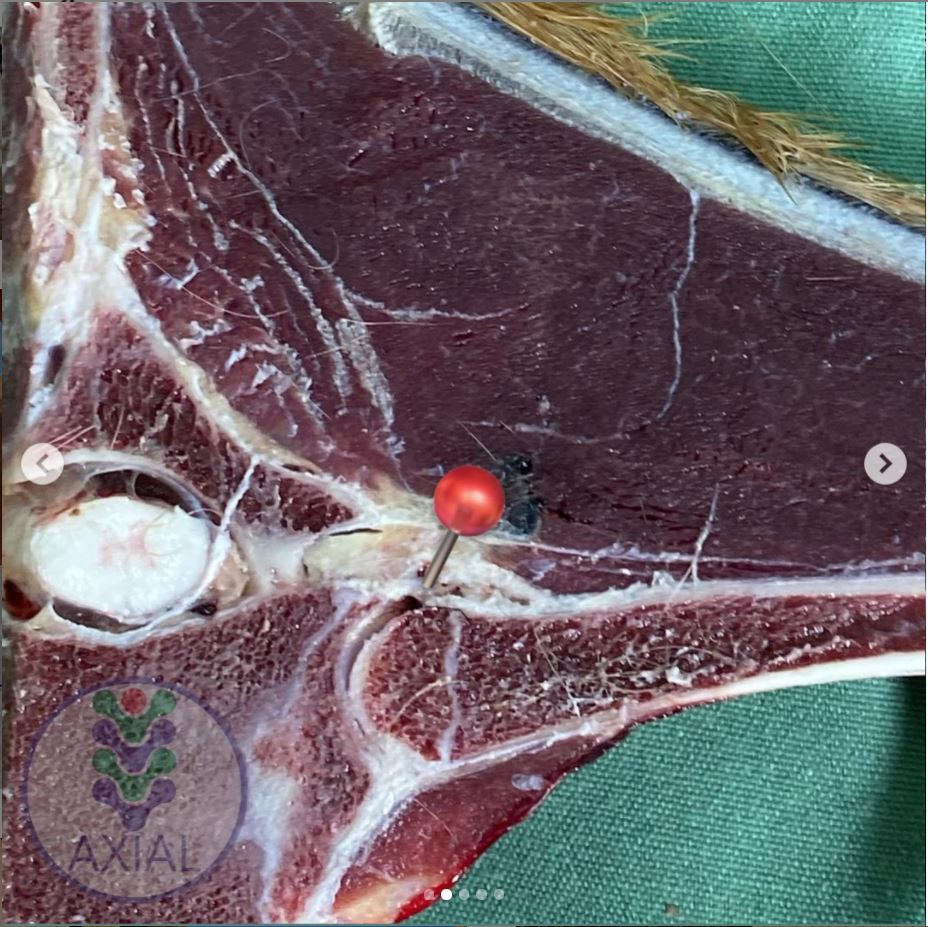

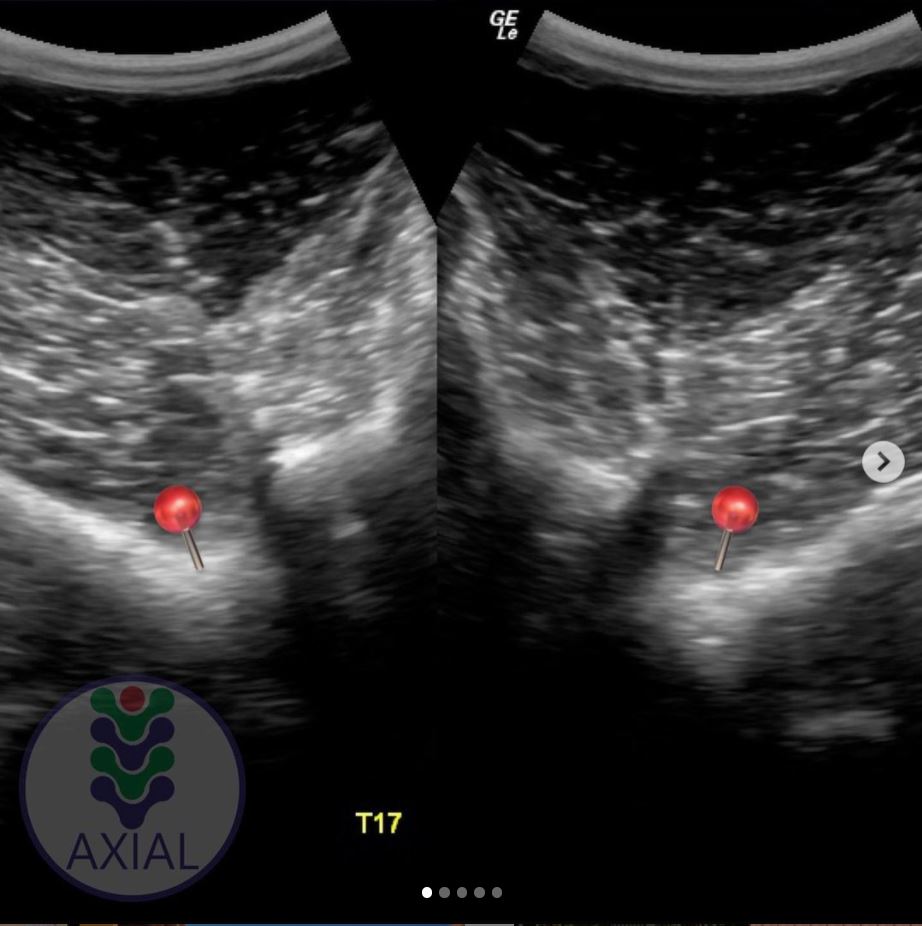

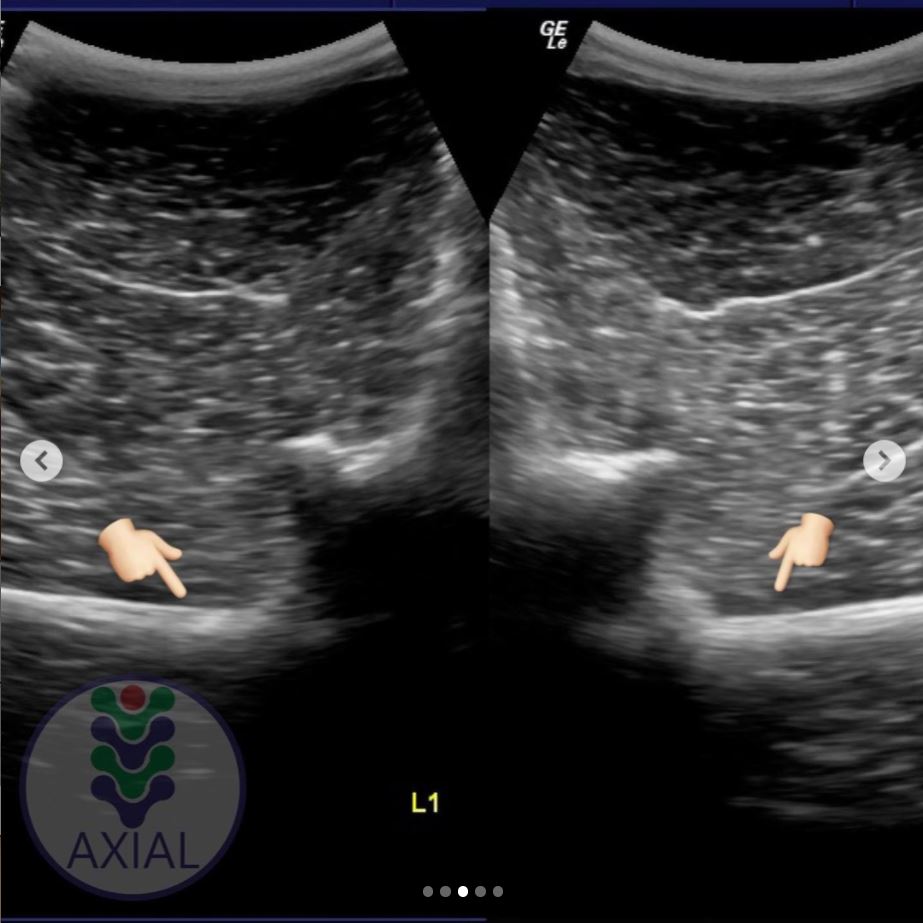

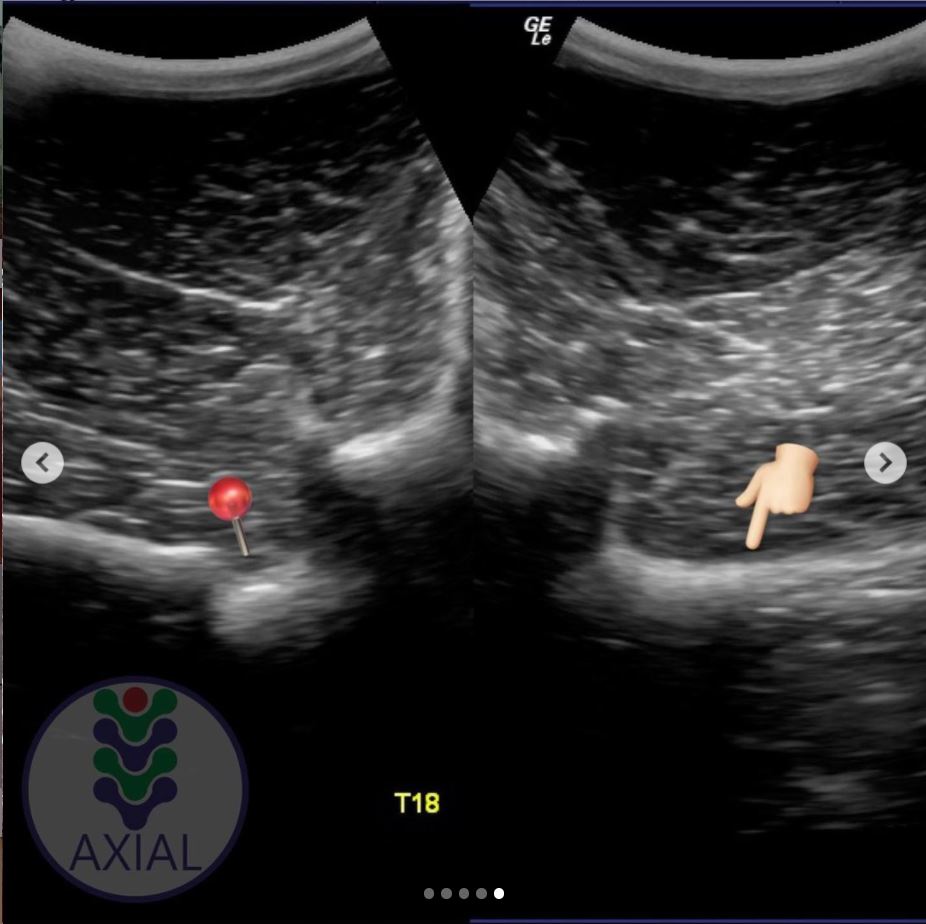

6. Imaging transitional vertebrae

6. Imaging transitional vertebrae You can follow her

You can follow her