They can lead to scoliosis, spinal arthritis, flexion and straightness problems, saddle fit issues, secondary lameness, hoof problems and soft tissue trauma. So, what on earth are transitional vertebrae, and why haven’t we heard more about them?

To answer the first part of that question, transitional vertebrae are hybrids that appear where one group of vertebrae changes to another. They show mixed features of each group.

They can be found along the spine, where:

- the cervical (neck) meet the thoracic vertebrae,

- the thoracic meet the lumbar vertebrae,

- the lumbar meet the sacral vertebrae (sacrum),

- where the sacrum meets the caudal vertebrae (tail bones).

As for why we’ve not heard much about them, the answer is probably that they’re rarely identified while a horse is alive.

However, they can lead to some very real problems in the living horse due to the asymmetry they cause along the spine – and they’re far more common than you might think.

The affected process or rib can hurt when the horse bends into it, as the abnormal rib/process is literally ‘stabbing’ into soft tissue.”

© All text copyright of the author, Jane Clothier, https://thehorsesback.com.

Thoracic and lumbar transitional vertebrae

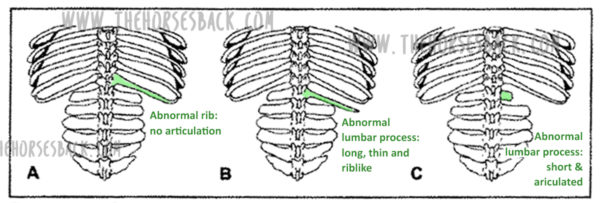

Here are the three main types of variation, as shown in this diagram from one of the few research papers to mention this issue.

Here, we’re going to look at the first two – labeled A and B – which are the most common manifestations.

A ‘process-like rib’ at T18

Labeled ‘A’ in the above diagram, this is a transitional vertebra at T18 (the last thoracic vertebrae) – a rib that thinks it might be a transverse process, lacking an articulation or joint with the vertebral body.

Instead, the process-like rib is solidly attached, meaning there is no independent movement whatsoever. At its end point, it’s joined by costal cartilage to the preceding rib, partially restricting that rib’s movement, too.

This is a problem, as the caudal ribs are not directly attached to the sternum because they need to move more.

The abnormality can be on one or both sides of the vertebra, although single side is most common.

A ‘rib-like process’ at L1

Labeled ‘B’ in the above diagram, this is a transitional vertebra at L1 (the first lumbar vertebrae). Again, it’s usually one-sided, although two sides also occur.

Here, we’re looking at a transverse process that rather than being fairly short, wide and flat, instead extends outwards like a misshapen rib. There’s no articulation with the vertebral body.

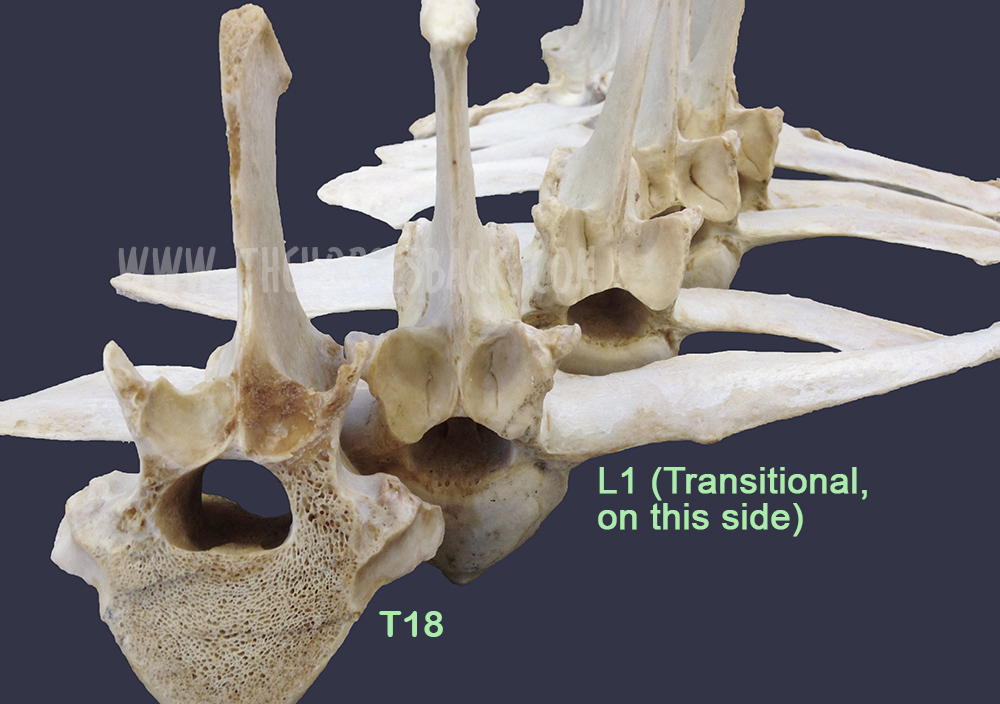

The above image shows an abnormal L1 found in a Quarter Horse mare. This mare was asymmetric throughout her body, and had a history of unsoundness both fore and rear throughout her lifetime.

Effect on the horse

Scoliosis is the major effect of transitional vertebrae. It’s an asymmetry that in these cases can be lifelong and permanent.

I’ve seen it a few times now in skeletons and on horses that have subsequently been euthanized for unrelated reasons – the spine curves in the affected direction, ie. the horse’s ‘short side’ is the same as the abnormal rib/process that is causing restriction.

The above bones were from a TB gelding who was in his late teens. Over his lifetime, the additional pressure on the side of the abnormal L1 had caused greater bone development in the vertebra further forward. In this photo, T18, the last thoracic vertebra, has been cut to show this impact.

Cases are highly individual and the degree of impact depends on how abnormal the vertebra is, plus other factors affecting the horse’s musculoskeletal balance – including tack and riders. However, we can consider the following points.

There can be an obvious localized effect:

- The affected process or rib can hurt when the horse bends into it, as it is literally ‘stabbing’ into soft tissue.

- The attachments of the deep, short muscles involved in segmental stabilization at L1 and T18 are affected, also affecting proprioception and posture.

- The abdominal muscles involved in breathing and flexion during locomotion are restricted over an affected T18.

- The diaphragm inserts onto T18, meaning its function is also affected.

This can affect overall spinal health and biomechanics:

- Scoliosis means that bending to the affected side can be uncomfortable, while bending to the opposite side can be highly limited.

- Achieving straightness may be impossible. Scoliosis can extend through the withers and into the neck.

- Impinging transverse processes and vertebral arthrosis at other vertebral joints further limit movement.

- These restrictions make lifting the back problematic.

And then there can be a host of secondary effects:

- In the heavily pregnant mare, existing discomfort due to a T18 may worsen.

- Achieving saddle fit is difficult on an asymmetric horse with scoliosis.

- Abnormal loading can lead to recurrent lameness and persistent hoof issues.

- Unrelated pathologies can scale up uncontrollably, as the horse cannot compensate effectively.

Take a closer look at the vertebrae featured in this article (Equine Healthworks is my practice page in NSW, Australia – also on Facebook.)

Questions, thoughts or comments? Join us at The Horse’s Back Facebook Group.

Can we spot transitional vertebrae in the living horse?

Yes, sometimes.

As this TB mare (above and below) was unable to maintain weight due to the physical stresses she was experiencing, her rib outline was fairly clear.

In her case, the last rib felt wider and flatter than the other ribs. The space between the rib and the point of hip was also noticeably narrower on the affected side (although this would be true of any horse with scoliosis, it’s a matter of putting the picture together, sign by sign).

There were other reasons for suspicion. Even when all the surrounding tissue was relaxed, there was no ‘spring’ when the rib was palpated with a flat hand. That’s not definitive, but it’s a cause for concern.

Do something that most people never do – stand on a fence or mounting block and take a photo down the horse’s spine, when it’s standing square…”

This veteran grey Arabian, below, is one I’d also consider a suspect. Again, we can see a very obvious protruding last rib on the offside and a lack of straightness. Even with musculoskeletal bodywork and spinal mobilization, the rib remained just as pronounced.

Incidentally, I’ve also worked on this horse’s offspring, and the younger horse has the same profile to the ribs, on the same side, accompanied by a history of inexplicable back pain – and lack of straightness.

Note: It’s important to eliminate other causes first, as horses will often have this appearance at the last rib, without it being caused by a transitional vertebra. What’s happening is that the rib is protruding because the vertebra is immobilised in a rotated position. When chiropractic, osteopathy or bodywork restores mobility to the spine, the rib returns to its normal position.

Ongoing hoof issues

In the bay TB mare, spinal asymmetry (scoliosis, with bend to the right) had led to excessive loading of the near fore. This was no doubt compounded by constantly training and racing in a clockwise direction, plus the classic long toe/low heel frequently found in ex-racehorses.

As a result, her near fore had constant hoof wall separation, bacterial infection (seedy toe / white line disease) and a deep P3 problem that would never come right.

Here’s the hoof capsule and P3. Yes, the poor girl suffered, despite extensive efforts to reconstruct that hoof.

Patreon members can view videos of this mare and further photos. Go to: www.patreon.com/thehorsesback for more details.

The TB gelding mentioned earlier also had chronic issues in the opposing fore hoof, with wall separation, damage to P3 and evidence of earlier laminitis.

How many horses are affected?

Who knows? The study mentioned earlier (Haussler et al, 1997) found that 22% of Thoroughbreds examined at necropsy, having died or been euthanized at the racetrack, had thoracolumbar transitional vertebrae.

To date, I’ve come across 3 in above-ground skeletons (2 x T18, 1 x L1), plus one in a horse later euthanized (1 x T18). These were TBs and Australian Stock Horses.

And as mentioned, I’ve suspected the T18 issue here and there amongst clients’ horses.

Although found mostly in Thoroughbreds, transitional vertebrae are seen across a range of breeds. And certainly, with equine dissection having taken off in quite a big way in the equine care industry, more and more of these anomalies are being observed.

Questions, thoughts or comments? Join us at The Horse’s Back Facebook Group.

Should we be concerned?

The answer is, inevitably, both yes and no.

On the positive side, if the numbers harbouring this problem are as high as it seems, we have to assume that many horses are coping just fine.

For as with any musculoskeletal anomaly, horses can compensate very well.

However, when another problem is added to the mix, things can head south very quickly indeed.

And it can all happen without us ever knowing that a skeletal anomaly is an underlying factor. When this happens, owners often have a lot of unanswered questions about their horses – and often large vets bills.

It’s the TB or TB-derived breed horse that is most likely to present this (although not exclusively). If you’re buying one and you view a horse with an obvious T18 that really stands out, you might want to get that checked.

At the very least, do something that most people never do – stand on a fence or mounting block and take a photo down the horse’s spine, when it’s standing square or close to square.

If there’s a clear scoliosis along the spine, be cautious (this is a good rule of thumb anyway, no matter what the cause is). If you see an overly pronounced rib on the concave side, be doubly cautious.

And if you believe your horse may have one, the answer is the same as always: be aware, take a 360 degree approach in ensuring that hooves, tack, training and riding are as good as they can be, and your horse will have the best possible chance of functioning well without cause for concern.