What if you were to learn that your horse is living with a hidden malformation? A skeletal abnormality that could be affecting it every day, changing the way it moves, creating a string of other physical problems, and possibly underlying the hard-to-pinpoint problems you’ve been noticing for months or even years ?

And that might even be causing a level of inherent instability that could be putting the rider in danger?

Sadly, this isn’t a hypothetical question. Instead it’s a reality that is only now being slowly uncovered.

And like the proverbial stone rolling down a mountain, the issue is gathering momentum as the equine industry, owners, breeders and researchers learn about it.

- It’s a skeletal malformation and it can’t be corrected.

- It’s congenital, ie inherited, so is present from birth.

- It has been in some lines of TBs for hundreds of years.

- It creates biomechanical issues due to asymmetry and lack of anchor points for key muscles.

- At its worst, it can contribute to neurological issues such as Wobbler syndrome.

- Some horses are so unstable, they are more prone to falling (not good news for jockeys).

- It can cause constant pain and associated behavioural changes.

- It’s primarily found in Thoroughbreds, Thoroughbred crosses and Warmbloods, but has also been identified in European breeds, Quarter Horses, Arabs and Australian Stock Horses.

Note: in the years since this post was written with direct support from Dr Sharon May-Davis, research has moved on. The body of literature now includes papers from Sharon and also from other researchers who do not reach similar conclusions about the issues caused by this malformation. I have included a list of journal papers and webinars on the topic at the end of the post, for reference if you wish to deepen your knowledge. You can also go view the full list here (opens in a fresh tab).

The problem behind this is ECVM, a congenital malformation of the C6 and C7 cervical vertebrae (ie, base of neck) – and it’s pretty nasty.

I’ve written about the work of Sharon May-Davis on this blog before and here I’m going to do so again. Through her many dissections per year, gross anatomist Sharon has become the first person to comprehensively document and quantify this problem.

In doing so, and publishing her findings in peer-reviewed journals, she has triggered a minor research avalanche as others take up the subject.

Update: since this article was published in July 2017, this malformation has been labelled Equine Complex Vertebral Malformation (ECVM). Some amendments have been made to include this term. To preserve existing links to the page, I’ve not updated the title and URL.

© All text copyright of the author, Jane Clothier, https://thehorsesback.com. No reproduction of partial or entire text without permission. Sharing the link back to this page is fine. Please contact me for more information. Thank you!

Twenty years + of research into ECVM

Sharon May-Davis’s path with this research began some 20 years ago. In February 1996, a Thoroughbred called Presley came down unimpeded in a race in Grafton, NSW, fracturing his pelvis, a hock bone, and right front fetlock.

Three years later, Sharon examined his bones, and saw something strange in his last two cervical vertebrae and his first ribs.

Fast forward to 2014, when Sharon published the first of her four peer-reviewed papers in the Journal of Equine Veterinary Science, concerning a congenital malformation in the sixth and seventh cervical (neck) vertebrae.

Although the problem had been mentioned briefly in papers, this was the first time that a researcher had accurately described and quantified the problem in its various forms.

Sharon’s unique perspective, gained as an anatomist who dissects between 15 and 20 horses per year, had certainly placed her in a position to do so.

The horse’s seven cervical vertebrae – made simple

Horses have seven vertebrae in their necks, labelled C1 to C7. Of these, four have unique shapes. Most horse people are familiar with C1, the first vertebrae known as the atlas, as it can be both seen and felt by hand with its distinctive ‘wing’ at the top of the neck.

Almost as well-known is C2, the second vertebrae, known as the axis.

Both atlas and axis have unique shapes for a special reason: they support the heavy skull and anchor the muscles that control the head’s movement.

Heading down the neck, C3, C4 and C5 are broadly similar in shape, with each being a bit shorter and blockier than the one above.

However, C6 and C7 are both slightly different on the ventral (lower) side, for here they provide insertion points for muscles arising from the chest.

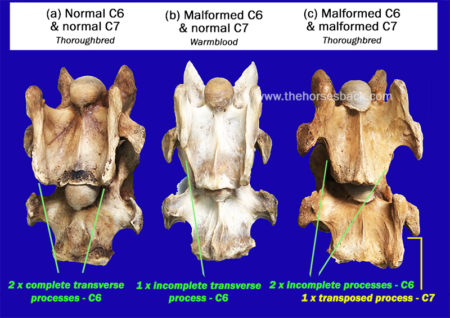

- C6 has transverse processes (the protrusions extending outwards) that are different to those of neighbouring bones, with two distinctive ridges running the vertebrae’s length. C6 also has two large transverse foramen, the openings that the arteries pass through.

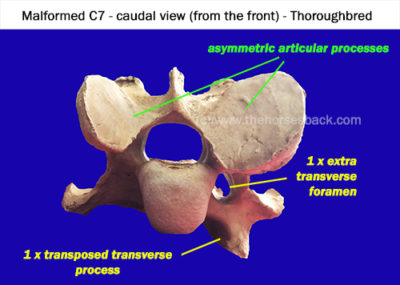

- C7 is the shortest and squattest cervical vertebrae of all. Its transverse processes are shorter, while there are also two facets that articulate with the first ribs. C7 has no transverse foramen.

At least, that’s how the vertebrae should be in a normal horse.

So, what is wrong with the malformed C6 and C7 vertebrae in ECVM?

In certain horses, these last two vertebrae are rather different, being malformed.

Sharon has identified the manifestations of this problem as a congenital (inherited) malformation affecting some Thoroughbred horses, and horses with Thoroughbred blood in their ancestry.

In C6, there is a problem with the two ridges of the transverse processes, as one or both can be partially absent.

When both are partially missing, it is common for one or two ridges (ie, parts of the transverse processes) to appear on C7 instead.

Also, the articular processes (the oval surfaces on the upper side, where each vertebrae links to its neighbours) can be radically different sizes. There can also be an additional arterial foramen or two.

The level of asymmetry can be radical.

The secondary problems the ECVM malformation causes

Being at the base of the neck, the asymmetry of C6 and C7 can cause alignment problems all the way up the vertebral column, leading to osteoarthritis of the articular facets.

It can also contribute to Wobbler Syndrome (Cervical Vertebral Stenotic Myelopathy), due to narrowing and/or malalignment of the vertebral foramen/canal, the opening through which the spinal cord passes. Not all Wobbler cases have this particular malformation, though.

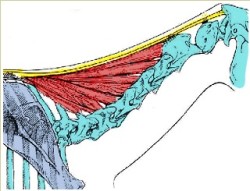

A further problem is that the lower part of the longus colli muscle, which is involved in flexing the neck, would normally insert on the transverse processes of C6 and C7. When these processes are malformed, the normal insertions are not possible.

This means there is a serious symmetry problem in the junction of the thorax and neck, which can have a deeper effect on the horse’s neurology and proprioception, as well as respiration.

In a few cases, horses with both the C6 and C7 problem also have malformations of the first sternal rib, on one or both sides. This can cause problems beneath the scapular and further issues with muscular attachments.

Associated stability problems can have far-reaching consequences for the horse, not to mention some serious safety issues for the rider. The safety issue can’t be stated often enough.

Why isn’t ECVM – the C6-C7 problem – more widely known ?

Why hasn’t this problem been noticed in regular veterinary interventions?

The answer is quite simple. While neurological issues may have been diagnosed, the exact cause has often remained hidden.

Both Thoroughbred horses and Warmbloods are known to have higher incidences of Wobbler Syndrome than other breeds, and while this is certainly not always due to C6-C7 malformation, the malformation has been found in some when dissected.

For example, the following dissection image appears in a veterinary account of large animal spinal cord diseases. It clearly shows a malformed C7 vertebrae, very similar to the one in the above image, but without giving any further categorisation.

The difficulty lies in the deep location of the lower cervical vertebrae. While normal radiographs can show all or some of C6, they are unable to penetrate the deeper tissues beneath the shoulder to image C7.

Nevertheless, the malformation can be identified in radiographs of C6, once you know where to look.

Since Sharon’s first paper appeared, the School of Veterinary Medicine, University of California, Davis, has reviewed its history of radiographs from horses with Wobbler Syndrome.

Researchers found that 24 cases out of 100 (close to 25%) showed malformation of one or both C6 transverse processes. This study also clarified how to identify the problem on standard radiographs of C6.

In another study, the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Utrecht University, completed CT scans on horses’ necks and found the various forms of the malformation in 26 horses out of 78 (33%). Unlike radiographs, the CT scans enabled identification of the C7 and first rib issues, although of course this imaging was conducted post mortem.

Is this rare, or are many horses affected?

While the problem has been identified primarily in TBs, it affects most breeds with TB blood in the ancestry to some degree.

Sharon May-Davis reports that to date, published, peer-reviewed journal papers have tallied 136 out of 471 horses as exhibiting congenital malformation of C6.

These have been in a range of breeds including Thoroughbreds (39%), Thoroughbred crosses (27%), Warmbloods and European breeds (30%), Quarter Horses (11%), and Arabs (11%). Standardbreds have also shown the problem, although the numbers included in studies are very small.

A common question is whether it’s known which TB lines predominantly carry this problem. The answer is: Yes. However, it is now so disseminated amongst the modern equine population beyond TBs, that it is of little help to identify them.

It must be remembered that these horses are those already brought to veterinary attention and/or euthanized for a related or unrelated reason, so the percentages may be higher than those for the general horse population. At the same time, the malformation might have played a major part in the horses’ decline, due to the many locomotory and postural problems it can lead to.

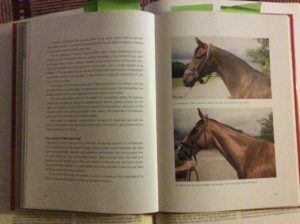

How do we identify these horses in life?

It’s all very well looking at these bones post mortem, you might say. Yet how can I tell if my horse has this problem? Or a horse that I might want to buy?

Some answers are forthcoming. As Sharon has frequently assessed horses before dissecting them – usually from video – she has been able to observe that many of these horses lack stability. (Indeed, in many cases, it is this very instability has directly led to the horse being euthanized, and ending up on the dissection table.)

As her research has progressed, she has also been able to identify many biomechanical and locomotion traits that make these horses ‘suspicious’ or at least ‘of interest’. Unsurprisingly, these problems have been particularly noticeable in horses with both a malformed C6 and C7.

For owners and equine professionals, here are some signs that can raise initial suspicions. All can also be caused by other problems, so a group of signs is more common than an individual indication.

- Some of these horses have a problem with standing square in front, and will always keep one foot further forward. This can persist despite all attempts to improve the horse’s body and to train the horse to halt squarely.

- Horses with the more serious malformations will often stand base-wide. Such horses can become very unbalanced on uneven ground, and sometimes in work. They easily become unbalanced when a hoof practitioner works on a forefoot.

- With such asymmetry in the skeletal structure, these horses have serious lateral flexion issues that can’t be overcome. When required to elevate the forehand, many will experience difficulties, due to the absence of correctly inserted musculature and incorrect articulation through the joints of the lower neck.

- A high level of asymmetry may be seen in the shoulders, with one scapula sometimes positioned very wide, with no improvement after chiro, osteopathy or bodywork. This is particularly so with the C6-C7 problem and associated first sternal rib abnormalities.

- There may be scoliosis along the entire spine.

- There may be an obvious scoliosis to the underside of the neck.

- The problem may lead to heavily asymmetric loading of the forefeet, so may be accompanied by a severe high foot/low foot issue (this is not in itself a sign of the C6-C7 problem).

If you suspect your horse has the C6-C7 issue

First, note that many horses do just fine with a C6 problem. It is those with the bilateral C6 and unilateral/bilateral C7 issue that tend to show the more worrying problems.

If your horse is showing ongoing signs of instability, it’s important to seek veterinary advice, so that neurological issues can be ruled out. (As this a recently recognised problem, it may be worth printing out the abstracts from the journal articles listed at the end of this page and handing them over.)

If the more severe malformations are identified by radiograph, it is important to remember that in some cases this can cause discomfort and pain to the horse, and it is not going to improve over time.

On the contrary, the cervical vertebrae of some older horses with the C6 and C7 malformations often display advanced osteoarthritis of the articular processes, as shown in the header image of a 19-year-old Thoroughbred’s malformed C7.

Where does this knowledge take us?

At the moment, that question is wide open. The findings published by Sharon May-Davis have triggered ongoing research on an international level. There are certainly ramifications for breeders in more than one equine sporting industry.

See Sharon May-Davis’s December 2020 presentation on ECVM here (article continues below):

Connections have been made with a number of falls on the racetrack that have caused injury, and worse, to both horse and jockey, as well as other runners. Similar things can be said for the sport of eventing, where unforced errors can have equally catastrophic effects.

It is entirely possible that at higher levels, pre-purchase examination radiographs will come to include a check on C6. While it’s not possible to radiograph the deeply positioned C7, we do at least know that this will only be present if the C6 anomaly exists.

Vets in some countries are proving faster at picking this up than others. While papers are being published, it clearly takes some time for information to filter down.

And until more is known, this problem is being unknowingly propagated every breeding season.

Of course, many horses harbouring the milder manifestations of this problem at C6 level are functioning very well. All horse owners can do is be aware that this issue exists, make use of this information if a problem arises, and await further research findings.

Literature on the malformation

In no particular order: the following peer reviewed journal articles address ECVM, as it is now known. Please remember when reading papers that no single paper proves one thing – a review of many papers and critical thinking is always essential. Apologies for not having standardized the formatting, but the links should be present.

- The Occurrence of a Congenital Malformation in the Sixth and Seventh Cervical Vertebrae Predominantly Observed in Thoroughbred Horses, May-Davis, Sharon, Journal of Equine Veterinary Science , Volume 34 , Issue 11 , 1313 – 1317

- Variations and implications of the gross morphology in the longus colli muscle in thoroughbred and thoroughbred derivative horses presenting with a congenital malformation of the Sixth and Seventh Cervical Vertebrae May-Davis, S, Walker, C. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science 35 (7), 560-568

- Characterization of the Caudal Ventral Tubercle in the Sixth Cervical Vertebra in Modern Equus ferus caballus. May-Davis, S., Dzingle, D, Saber, E., Blades Eckelbarger, P. Animals 13 (14), 2384

- Morphology of the Ventral Process of the Sixth Cervical Vertebra in Extinct and Extant Equus: Functional Implications, May-Davis, S., Hunter, R, White, R. Animals 13 (10), 1672

- Variations and Implications of the Gross Morphology in the Longus colli Muscle in Thoroughbred and Thoroughbred Derivative Horses Presenting With a Congenital Malformation of the Sixth and Seventh Cervical Vertebrae, May-Davis, Sharon et al., Journal of Equine Veterinary Science , Volume 35 , Issue 7 , 560 – 568

- Congenital Malformations of the First Sternal Rib, May-Davis, Sharon, Journal of Equine Veterinary Science , Volume 49 , 92 – 100

- Ex Vivo Computated Tomographic Evaluation of Morphology Variations in Equine Cervical Vertebrae, Veraa, S. et al, Veterinary Radiology & Ultrasound, Vol. 57, Issue 5

- Prevalence of Anatomical Variation of the Sixth Cervical Vertebra and Association with Vertebral Canal Stenosis and Articular Process Arthritis in the Horse, Spriet, M. and M Aleman, Veterinary Radiology & Ultrasound, Vol. 57, Issue 3

- Anatomical Variation of the Spinous and Transverse Processes in the Caudal Cervical Vertebrae and the First Thoracic Vertebra in Horses, Santinelli, I. et al, Equine Veterinary Journal, Vol. 48, 45–49

- Congenital variants of the ventral laminae of the sixth and seventh cervical vertebrae are not associated with clinical signs or other radiological abnormalities of the cervicothoracic region in Warmblood horses. Dyson S, Phillips K, Zheng S, Aleman M. Equine Veterinary Journal, 2025 Vol.2 :419-430

- Neck pain but not neurologic disease occurs more frequently in horses with transposition of the ventral lamina from C6 to C7. Henderson CS, Story MR, Nout-Lomas YS. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2024 May 29;262(9):1215-1221

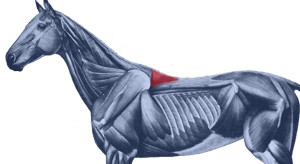

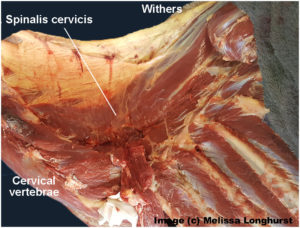

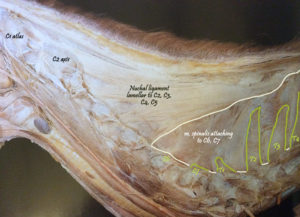

At best, it has no more than a bit part in anatomical illustrations, usually as a small triangular area at the base of the withers. This is also where we can palpate it.

At best, it has no more than a bit part in anatomical illustrations, usually as a small triangular area at the base of the withers. This is also where we can palpate it. Further back along the spine, it lies medially to Longissimus dorsi, and in fact integrates with this larger, better known muscle, attaching to the processes of the lumbar and thoracic vertebrae.

Further back along the spine, it lies medially to Longissimus dorsi, and in fact integrates with this larger, better known muscle, attaching to the processes of the lumbar and thoracic vertebrae. Its integration with other muscles is complex, and its close relationship with Longissimus dorsi partially explains why it doesn’t get much consideration as a muscle in its own right.

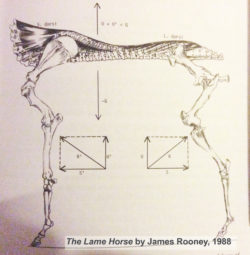

Its integration with other muscles is complex, and its close relationship with Longissimus dorsi partially explains why it doesn’t get much consideration as a muscle in its own right. In his 1980s’ Guide to Lameness videos, Dr. James Rooney, first director of the Gluck Equine Research Center, University of Kentucky, referred to Spinalis as part of the suspension bridge of muscles supporting the spine (Longissimus dorsi achoring from the lumbosacral vertebrae, Spinalis thoracis et dorsalis from the upper thoracics). He also refers to this extensively in The Lame Horse (1988).

In his 1980s’ Guide to Lameness videos, Dr. James Rooney, first director of the Gluck Equine Research Center, University of Kentucky, referred to Spinalis as part of the suspension bridge of muscles supporting the spine (Longissimus dorsi achoring from the lumbosacral vertebrae, Spinalis thoracis et dorsalis from the upper thoracics). He also refers to this extensively in The Lame Horse (1988).

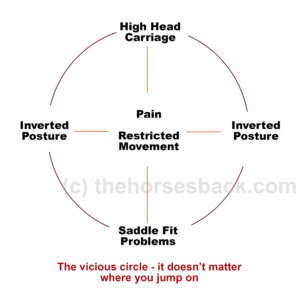

What often happens is this. An overtight saddle fits over the base of the withers like a clothes peg, pinching Trapezius thoracis and Longissimus dorsi. However, it frequently misses Spinalis thoracis where it surfaces, wholly or partially within the gullet space. Often, the muscle is partially affected.

What often happens is this. An overtight saddle fits over the base of the withers like a clothes peg, pinching Trapezius thoracis and Longissimus dorsi. However, it frequently misses Spinalis thoracis where it surfaces, wholly or partially within the gullet space. Often, the muscle is partially affected.

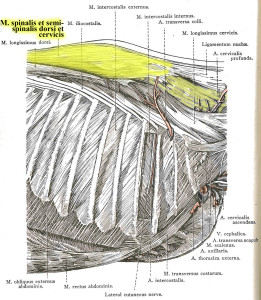

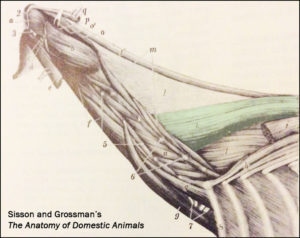

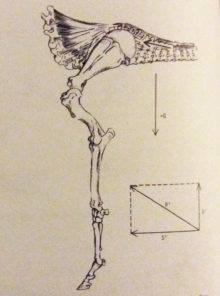

The muscle is tinted green in this image from Sisson and Grossman’s The Anatomy of Domestic Animals, Volume 1, fifth edition 1975. Here, it is labelled Spinalis et semi-spinalis cervicis. This anatomical figure is credited to an earlier text, Ellenberger and Baum, 1908. (added 23 Dec 2016)

The muscle is tinted green in this image from Sisson and Grossman’s The Anatomy of Domestic Animals, Volume 1, fifth edition 1975. Here, it is labelled Spinalis et semi-spinalis cervicis. This anatomical figure is credited to an earlier text, Ellenberger and Baum, 1908. (added 23 Dec 2016)

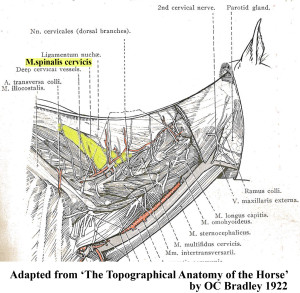

Master Saddler Jochen Schleese refers to Spinalis dorsi and its function in stabilizing the withers in Suffering in Silence, his passionate book about saddle fitting from 2014. “This muscle area is especially prone to significant development – especially with jumpers – because it is continually contracted to accommodate the shock of landing”. The surface area of the muscle is indicated in the anatomical figure, reproduced here. (added 23 Dec 2016)

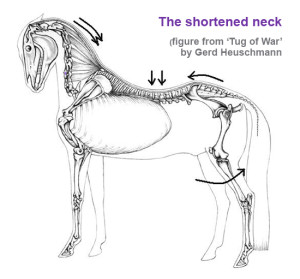

Master Saddler Jochen Schleese refers to Spinalis dorsi and its function in stabilizing the withers in Suffering in Silence, his passionate book about saddle fitting from 2014. “This muscle area is especially prone to significant development – especially with jumpers – because it is continually contracted to accommodate the shock of landing”. The surface area of the muscle is indicated in the anatomical figure, reproduced here. (added 23 Dec 2016) In his seminal text addressing issues of modern dressage training, Tug of War, 2007, Gerd Heuschmann includes Spinalis cervicis in the triangle formed by the rear of the rear of the cervical spine, the withers, and the shoulder blades, “… an extensive connection between the head-neck axis and the truck… it explains how the position and length of the horse’s neck directly affects the biomechanics of the back.” (added 31 Dec 2016)

In his seminal text addressing issues of modern dressage training, Tug of War, 2007, Gerd Heuschmann includes Spinalis cervicis in the triangle formed by the rear of the rear of the cervical spine, the withers, and the shoulder blades, “… an extensive connection between the head-neck axis and the truck… it explains how the position and length of the horse’s neck directly affects the biomechanics of the back.” (added 31 Dec 2016)