Achieving good saddle fit with Arabian horses can be challenging on account of some breed-typical features that make their backs somewhat complicated. You can correct one issue and run immediatley into another, for there’s often very little wriggle room when it comes to the Arabian back.

Of course, not all horses in a single breed are the same, as there are many variations in conformation and posture. However, saddle fitters usually agree that Arabians can be the trickiest of customers to fit.

This post introduces some commonly seen issues, so you can look at your Arabian’s body with a clearer understanding of what’s happening with a saddle (mis)fit, and what you need to be looking for as you try to move forwards.

The Arabian Horse and Saddle Fit Problems

Here are the conformational points that feed into many Arabian saddle fit issues. Arabians display some or all of these features:

- Compact and short-coupled

- Wide flat back

- Well sprung ribcage

- Long set back withers

- High croup

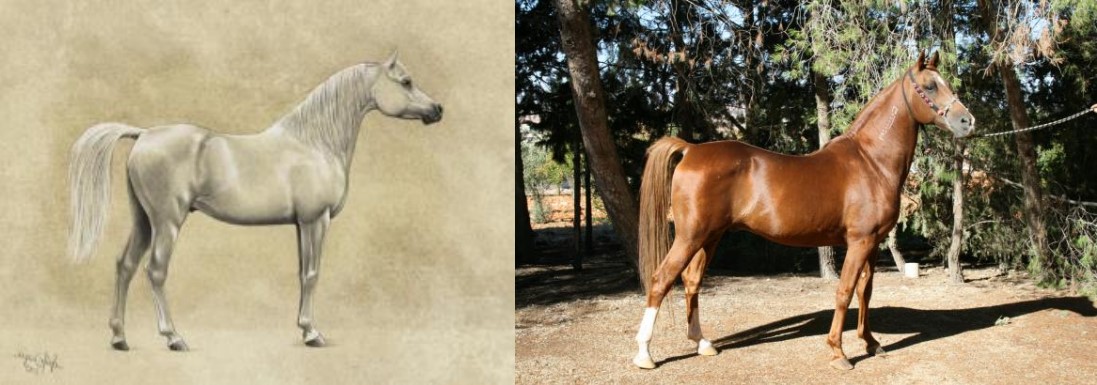

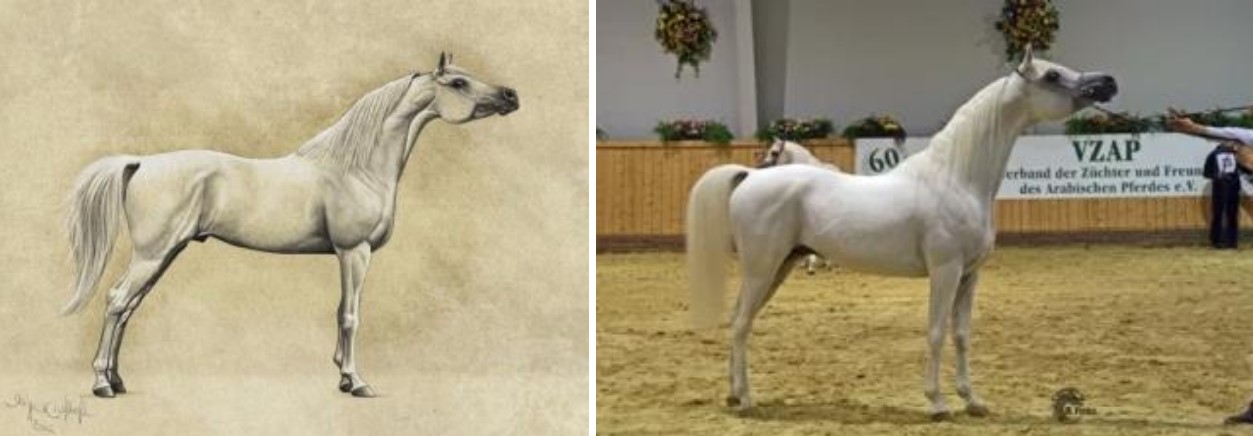

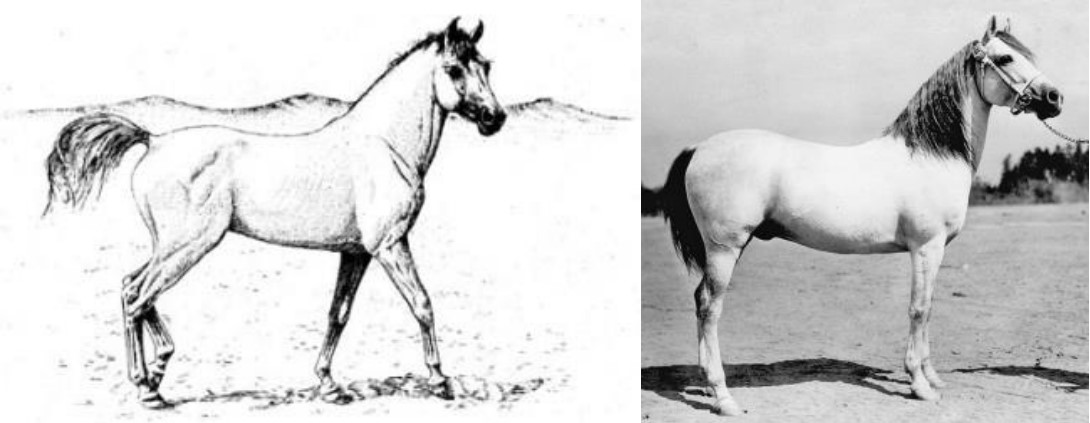

The combination of these features varies between the main strains of Arabians as well as individual breeding lines.

Briefly, strains are breed subgroups, often named after the Sheikhs or tribes that bred them. Each strain has subtle variations in physical features, temperament, and abilities. Some are pictured in this post, purely to help us see the influences on modern conformation more clearly.

To make these features’ interaction in saddle fit easier to understand, I’ve organised these conformation points within three sections in this post.

1. A Short Wide Back

As a breed, Arabians probably come with more legends attached than any other. One of these is usually accepted without question: that the breed has one fewer rib than other breeds.

If you talk to an equine anatomist with decades of experience, you’ll hear that most Arabians have the regular number of thoracic vertebrae (18), but some have fewer lumbar vertebrae (five instead of six).

This does shorten the back overall and brings the last rib closer to the point of hip, creating a short-coupled horse.

How does this affect saddle fit on its own?

First, the round ribcage may lead to the saddle rolling. As it is usually accompanied by a forward girth ‘groove’, choice of girth becomes especially important.

An anatomical girth that clears the elbows and is wider in the centre (for a wide barrelled horse with a flat sternal area) may assist with stabilising the saddle.

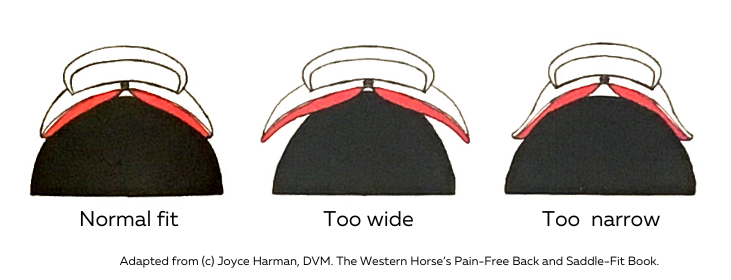

So as well as clearing the wither, the saddle must be wide enough to accommodate the ribcage and well-muscled back in the fit horse.

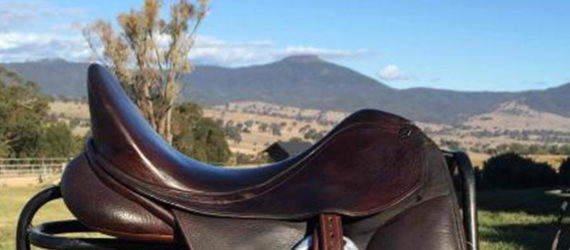

Western trail saddles recommended for Arabians have shorter skirts with wider gullets, and a bit more curve along the length. English style saddles are usually wide, with wider, flatter and thinner panels.

2. Low to Medium Withers

The saddle area is shortened by the long set-back wither, which is an aspect of the deep chest, high set neck, and laid back shoulder.

As well as being long, Arabian withers are frequently low and well-covered, with heavy muscle at their base.

A wide, hoop style tree is often the answer for English style saddles.

Western saddles, as well as being shorter with rounded skirts that won’t impact the point of hip, may have need to have more flare in the bars to accommodate the wide shoulders and scapular movement.

Arabians may also have withers of a more middling height, which also widen out into a rounded ribcage. If the horse’s back is fairly flat along the topline, then the tree and panels need to be straighter too.

With these horses, the saddle gullet needs to be higher, but still have enough width to accomodate the shoulder and rib cage. (Of course, if the horse is a lot finer, then narrow may be what is needed.)

Fitting around the broad muscle at the base of the neck is not achieved by simply widening a synthetic saddle by swapping gullet plates – doing so will make the saddle more curved along its length, which isn’t suitable for a horse with a straight back. On these horses, the saddle may rock.

3. Height of Croup

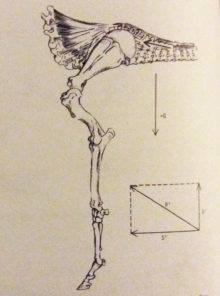

Arabians are known for their relatively long, level croup (top of the hindquarters) and naturally high tail carriage. The height of the pelvis at the sacral tuberosities (the bony peak) may be as high as the withers, or indeed higher. This may be obscured in images where the horse’s hind legs are extended out.

There is already a potential issue because when the lumbar spine is short, it must sweep up to the pelvis at a steeper angle than with a longer lumbar spine.

Add to this a topline built from full curves – the Arabian’s famous flowing lines – and a definite dip in the thoracic spine (saddle area). The upward sweep to the pelvis is now more accentuated.

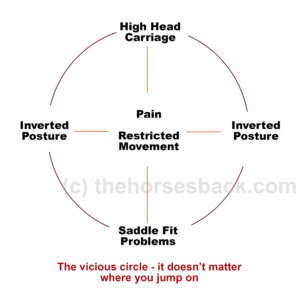

A postural issue also comes into play, as a naturally high head carriage dips the spine further (ie. hollowing the back).

Two things can now be happening.

If low broad withers are accompanied by a higher croup, there may be issues with the saddle sliding forwards. The saddle may be unstable and will roll easily on the horse’s rounded body – more so than if the croup is level with the withers.

The bigger issue is that the saddle may bridge between the lumbar muscles and the set back withers and muscles, creating pressure at these points.

If both of the above are happening at once, the saddle may both press into the shoulders and roll from side to side, creating a very uncomfortable and potentially painful experience for the horse, and little stability for the rider.

In these cases, saddles may need shorter tree and panels to avoid resting on the upswept lumbar spine.

But it can’t be small: it still needs sufficient width to clear the spine and the withers, and to sit across those wide back muscles with a good, even contact.

The Complex Arabian

As we can see, the combined issues that can arise with Arabian conformation require us to think about the shape of the saddle tree along every inch of its length and width.

Only once their complicated conformation is understood, can great saddle fit be achieved.

Thankfully, there are many saddles out therem including Arabian-specific models, which are becoming more and more finely tuned.

It has to be said we must thank the world of endurance riding for many of the more innovative solutions, with special designs created to accomodate the conformation and movement of this remarkable breed.

Useful saddle fitting resources

This article introduces the problems, so what about solutions?

The following resources provide more information on getting your saddle fit right (I’ll add more soon!)

Western Saddle Fit – The Basics 67-minute video on DVD or Vimeo streaming from Rod and Denise Nikkel

Western Saddle Fit: Well Beyond the Basics 6 hours for equine professionals from Rod and Denise Nikkel

The Horse’s Pain-Free Back and Saddle-Fit Book eBook from Joyce Harman DVM

The Western Horse’s Pain-Free Back and Saddle-Fit Book Soundness and comfort with back analysis and correct use of saddles and pads, from Joyce Harman DVM

Saddlefit4Life YouTube channel presents numerous educational videos, from Jochen Schleese of Schleese Saddlery.

There’s a basic premise of saddle fitting that hasn’t occurred to a lot of people. It can’t have done, not if the tack they’re riding in is anything to go by.

There’s a basic premise of saddle fitting that hasn’t occurred to a lot of people. It can’t have done, not if the tack they’re riding in is anything to go by. The reason for this statement is simply to highlight the fact that inserting a relatively static piece of equipment between two living organisms in motion is, at best, always going to be fraught with complexity.

The reason for this statement is simply to highlight the fact that inserting a relatively static piece of equipment between two living organisms in motion is, at best, always going to be fraught with complexity.

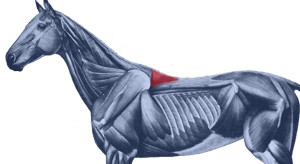

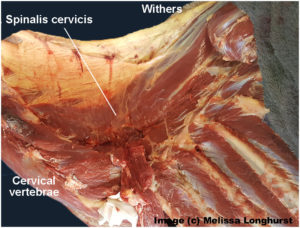

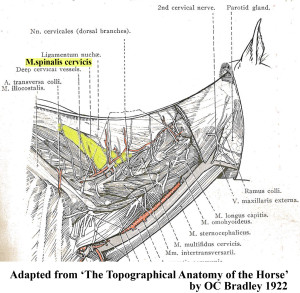

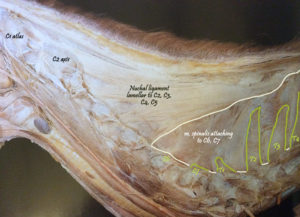

At best, it has no more than a bit part in anatomical illustrations, usually as a small triangular area at the base of the withers. This is also where we can palpate it.

At best, it has no more than a bit part in anatomical illustrations, usually as a small triangular area at the base of the withers. This is also where we can palpate it. Further back along the spine, it lies medially to Longissimus dorsi, and in fact integrates with this larger, better known muscle, attaching to the processes of the lumbar and thoracic vertebrae.

Further back along the spine, it lies medially to Longissimus dorsi, and in fact integrates with this larger, better known muscle, attaching to the processes of the lumbar and thoracic vertebrae. Its integration with other muscles is complex, and its close relationship with Longissimus dorsi partially explains why it doesn’t get much consideration as a muscle in its own right.

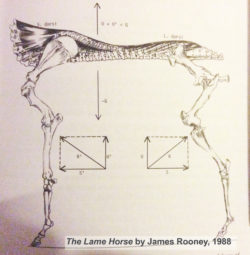

Its integration with other muscles is complex, and its close relationship with Longissimus dorsi partially explains why it doesn’t get much consideration as a muscle in its own right. In his 1980s’ Guide to Lameness videos, Dr. James Rooney, first director of the Gluck Equine Research Center, University of Kentucky, referred to Spinalis as part of the suspension bridge of muscles supporting the spine (Longissimus dorsi achoring from the lumbosacral vertebrae, Spinalis thoracis et dorsalis from the upper thoracics). He also refers to this extensively in The Lame Horse (1988).

In his 1980s’ Guide to Lameness videos, Dr. James Rooney, first director of the Gluck Equine Research Center, University of Kentucky, referred to Spinalis as part of the suspension bridge of muscles supporting the spine (Longissimus dorsi achoring from the lumbosacral vertebrae, Spinalis thoracis et dorsalis from the upper thoracics). He also refers to this extensively in The Lame Horse (1988).

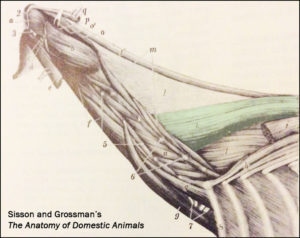

What often happens is this. An overtight saddle fits over the base of the withers like a clothes peg, pinching Trapezius thoracis and Longissimus dorsi. However, it frequently misses Spinalis thoracis where it surfaces, wholly or partially within the gullet space. Often, the muscle is partially affected.

What often happens is this. An overtight saddle fits over the base of the withers like a clothes peg, pinching Trapezius thoracis and Longissimus dorsi. However, it frequently misses Spinalis thoracis where it surfaces, wholly or partially within the gullet space. Often, the muscle is partially affected.

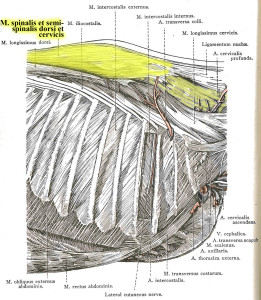

The muscle is tinted green in this image from Sisson and Grossman’s The Anatomy of Domestic Animals, Volume 1, fifth edition 1975. Here, it is labelled Spinalis et semi-spinalis cervicis. This anatomical figure is credited to an earlier text, Ellenberger and Baum, 1908. (added 23 Dec 2016)

The muscle is tinted green in this image from Sisson and Grossman’s The Anatomy of Domestic Animals, Volume 1, fifth edition 1975. Here, it is labelled Spinalis et semi-spinalis cervicis. This anatomical figure is credited to an earlier text, Ellenberger and Baum, 1908. (added 23 Dec 2016)

Master Saddler Jochen Schleese refers to Spinalis dorsi and its function in stabilizing the withers in Suffering in Silence, his passionate book about saddle fitting from 2014. “This muscle area is especially prone to significant development – especially with jumpers – because it is continually contracted to accommodate the shock of landing”. The surface area of the muscle is indicated in the anatomical figure, reproduced here. (added 23 Dec 2016)

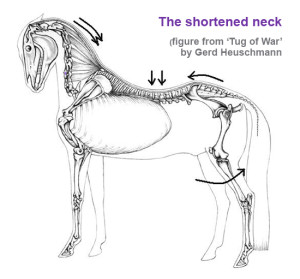

Master Saddler Jochen Schleese refers to Spinalis dorsi and its function in stabilizing the withers in Suffering in Silence, his passionate book about saddle fitting from 2014. “This muscle area is especially prone to significant development – especially with jumpers – because it is continually contracted to accommodate the shock of landing”. The surface area of the muscle is indicated in the anatomical figure, reproduced here. (added 23 Dec 2016) In his seminal text addressing issues of modern dressage training, Tug of War, 2007, Gerd Heuschmann includes Spinalis cervicis in the triangle formed by the rear of the rear of the cervical spine, the withers, and the shoulder blades, “… an extensive connection between the head-neck axis and the truck… it explains how the position and length of the horse’s neck directly affects the biomechanics of the back.” (added 31 Dec 2016)

In his seminal text addressing issues of modern dressage training, Tug of War, 2007, Gerd Heuschmann includes Spinalis cervicis in the triangle formed by the rear of the rear of the cervical spine, the withers, and the shoulder blades, “… an extensive connection between the head-neck axis and the truck… it explains how the position and length of the horse’s neck directly affects the biomechanics of the back.” (added 31 Dec 2016)