The ex-racehorse: a huge heart, a strong work ethic, great athleticism, wonderful sensitivity… and, potentially, a host of physical issues. Are you able to identify the problems so often present in these superb equine athletes?

A sports career can be tough on the body, as any committed athlete will admit. No matter how successful the athlete, the wear and tear and dings and dents will just keep on coming. It’s an inevitable consequence of making the body work at its outer limits of strength, speed and endurance: there are going to be times when the body just can’t make it or just can’t take the pressure. And that doesn’t count the spills and collisions that happen along the way. The same is as true for any top athlete as for any trainee who doesn’t make it past the foothills of success. And the same is definitely as true for racehorses as for any human Olympiad.

All text (c) Jane Clothier, https://thehorsesback.com No reproduction without permission. Thanks!

The damage carried by ex-racehorses

Just how much damage an ex-racehorse displays in its physique depends on several things:

Just how much damage an ex-racehorse displays in its physique depends on several things:

- the methods of training used,

- the speed with which the training was introduced and stepped up,

- the athletic qualities of that horse’s body – conformation, maturity and sheer unquantifiable athleticism,

- the treatment given and recovery time allowed for injuries at the time they occurred – assuming all were recognized (not all are visible or obvious),

- the demands placed on the horse in terms of number of races and recovery time between races,

- the length of time spent in racing, enabling the above to occur,

- the horse’s mental and emotional ability to cope with physical problems (it varies enormously).

As in any sport, there are things that are done well, and things that are not done so well. Informed training and misinformed. Well judged and misjudged. Just as in the rest of the equine world.

As in any sport, there are things that are done well, and things that are not done so well. Informed training and misinformed. Well judged and misjudged. Just as in the rest of the equine world.

Some thoroughbreds come out of the racing industry in fine fettle and have splendid second athletic careers in high end competition. Many have lower level issues that come right with some rehabilitation, leaving them suited to successful but less demanding careers. Others may be more suited to recreational homes, where life is one long pleasurable trail ride.

Unfortunately, many thoroughbreds with moderate problems land up in homes with people who are quite unaware of their horses’ issues.

What would you look for when buying an ex-racehorse?

When working with clients, I see a range of issues that come up again and again in ex-racehorses. I also see plenty of unsuspecting owners who didn’t know what they were buying at the time.

When working with clients, I see a range of issues that come up again and again in ex-racehorses. I also see plenty of unsuspecting owners who didn’t know what they were buying at the time.

There’s a huge amount of love around, but the horse is often showing discomfort or pain, and the owner is only just realizing that (a) their horse may not be able to participate in the activities they’d hoped to experience together, and (b) getting the horse to a point when they can deal with these issues may cost considerably more than the horse did upon purchase.

It’s a sad situation. I believe that when looking at ex-racehorses, even those that have already had a couple of non-racing owners, you could do a lot worse than check for the physical issues listed here. Even better, get a vet to check the horse… but even then, you could run through this checklist before getting the vet in.

Don’t forget to read this guest post: 8 Golden Rules for Helping Your Thoroughbred Get Right Off The Track

There’s functional and not-so-functional when it comes to ex-racehorses

Not all the physical issues are deal-breakers, of course. A horse can have one or two and still be able to function perfectly well (although if it’s straight out of racing, some rehabilitative work is going to be necessary). A big part of your buying decision will come down to:

- the number of issues you can identify,

- the severity of those issues,

- what has already been done to assist the horse with those issues,

- how much they will affect the kind of riding you wish to do, and

- whether YOU are capable of providing the rehabilitation and retraining needed to support the horse through those problems – or if not, whether you can afford to pay somebody else who can.

The list that follows is by no means exhaustive – there are always more problems, especially as a combination of different problems can throw up further secondary issues. And I don’t go into hoofcare, which is worthy of another introductory article in its own right. However, it’s a major issue, so I’d recommend learning more about that too.

What I’ve decided to focus on here are problems that you can identify quickly and relatively easily. Most are visually identifiable. You can then get a more knowledgeable person to help you assess the horse or get a vetting completed before making a decision. Better still, do both.

1. Sacroiliac Damage – Not Whether it’s There, but is it Slight, Bad or Appalling?

1. Sacroiliac Damage – Not Whether it’s There, but is it Slight, Bad or Appalling?

This problem really is the number one, as every ex-racehorse has damage to the ligaments in this area. Depending on severity, there can be lesions that have healed, or lesions that have resulted in lasting weakness.

Frequently, when damage to the ligaments is severe, there’ll be further changes to the pelvis that are also visible. These may may or may not have the same root cause (see 2, below). One general rule, though, is that the horse won’t be symmetrical.

Major damage can rule out a future athletic career, while moderate damage may require rehabilitative work to strengthen the back and prepare the horse for future work. Minor damage isn’t necessarily an issue once the ligaments have healed.

Major damage can rule out a future athletic career, while moderate damage may require rehabilitative work to strengthen the back and prepare the horse for future work. Minor damage isn’t necessarily an issue once the ligaments have healed.

Check for: asymmetry of the tuber sacrales (the two bony ‘pins’ of the croup), with one side being more than 5mm higher than the other. The horse may walk with one side of the pelvis lifting higher than the other – a hip ‘hike’. The muscle development over the glutes on top of the hindquarters may be uneven. These horse are nearly always cagey about picking up a back foot – they’ll swiftly lift it really high and then lower it into position. The horse can also find it hard to stand square, instead standing with hind feet close together – one toe may be angled outwards. Always look for problems with the lumbar spine as well (see 3, below).

2. The Pelvis Can Be Equine Ground Zero

2. The Pelvis Can Be Equine Ground Zero

As well as sacroiliac problems, ex-racehorses can have other structural damage to the pelvis. Some of it you can see, some of it you can’t. The most important thing to do is check the pelvis for overall symmetry. What you’re checking for isn’t just pelvic rotation, ie. one side being higher or further forward than the other, but also distortion.

In horses that have had heavy accidents at a young age, the pubic symphysis (the lower cartilaginous join between the pelvic halves, directly between the legs) hasn’t formed properly. The pelvis may be forced wider due to impact or stress, and this part never joins.

In horses that have had heavy accidents at a young age, the pubic symphysis (the lower cartilaginous join between the pelvic halves, directly between the legs) hasn’t formed properly. The pelvis may be forced wider due to impact or stress, and this part never joins.

What problems does this cause? With a severely distorted pelvis, a horse can’t work equally well on both reins and may not be able to canter at all on one rein. These horses also have a higher risk of having hidden stress fractures – hairline fractures that can worsen after a further fall or trauma later in life.

Indeed, make sure that all the pelvic ‘bony landmarks’ – the point of hip, point of buttock, croup – are actually present. Sometimes fractures lead to ‘knocked down hips’ or one tuber sacral may have dropped due to a fracture of the pelvic wing.

Check for: Pelvic symmetry, by checking the positions of the bony landmarks. If you know the horse and it’s safe, stand on a box a few feet behind to take a look down the back of the squared up horse (if it can square up, that is). Otherwise, hold a mobile phone directly overhead to get a straight-down-the-back photo, ensuring it’s dead center. ALWAYS STAY IN A SAFE POSITION – CLIMB ON A FENCE TO LOOK, WHATEVER. JUST STAY SAFE.

© All text copyright of the author, Jane Clothier, www.thehorsesback.com. No reproduction of partial or entire text without permission. Sharing the link back to this page is fine. Please contact contact me for more information. Thank you!

3. Heading North, South, East or West… the Lumbar Spine

3. Heading North, South, East or West… the Lumbar Spine

If you’ve found any sacroiliac or pelvic issues, you’ll probably find problems in the lumbar spine too. Lateral imbalance in the pelvis will, more often than not, rotate the lumbar spine to one side or the other. Lumbar issues can also be found all on their own.

A long-term rotated lumbar spine will usually have some fusion between the vertebrae, and/or overriding dorsal processes (the part of the vertebrae you can feel). Fused areas are painful for the horse while they’re happening, and OK once the fusion is complete. But if fusion cracks, it can once more be extremely painful. Many horses compete just fine with some fusion, but if it’s severe, there’ll be problems with flexion, both vertical and lateral.

A long-term rotated lumbar spine will usually have some fusion between the vertebrae, and/or overriding dorsal processes (the part of the vertebrae you can feel). Fused areas are painful for the horse while they’re happening, and OK once the fusion is complete. But if fusion cracks, it can once more be extremely painful. Many horses compete just fine with some fusion, but if it’s severe, there’ll be problems with flexion, both vertical and lateral.

Check for: Use your hand to check the lumbar spine for the ‘lumps and bumps’ that can indicate overriding processes. Looking from the side, is the lumbar spine raised – ie, a roached back? This will usually tilt the pelvis back if it’s a longer term problem. If the pelvis is tilted forward, you’ll find there’s often a longer dip in front of the croup – the sacrolumbar gap is larger than normal.

4. Knee Bones: Take a Bag of Chicklets and Shake Them Up

4. Knee Bones: Take a Bag of Chicklets and Shake Them Up

Or so said Tom Ivers, one of the original equine sports therapy experts and a racing trainer to boot. Equine knees are delicate and complex, with many small bones (carpals), and undergo a lot of stress in a racing career.

Problems such as slab fractures and bone chips in the carpal bones happen due to over-extension (when the joint is bent back slightly) at high speed, or from constant loading on the same bend. Then there are more complex fractures, when the carpal bones break into more than two segments.

Check for: Puffiness around the joint, especially in front, due to previous swelling in the joint capsule. Old bone chips and slab fractures may have been dealt with at the time, but there can be lasting damage within the joint that leads to osteoarthritis (carpitis) later on.

5. The Stresses Left by Sore Shins

5. The Stresses Left by Sore Shins

An ex-racehorse may have had an episode of sore shins in its early career. This is stress to the periosteum (the soft surface layer over the bone) caused by concussion – the body’s response is to lay down extra calcium to strengthen the bone. The bone recovers, but anywhere there’s been remodeling, there’s weakness in the bone.

If it’s severe, there may be an undiagnosed stress fracture that can go catastrophic under high pressure at a future date.

Check for: a curvature on the front of the cannon, which indicates that the problem was bad for heavy remodeling to occur.

6. Tendons, Tendons and More Damaged Tendons

6. Tendons, Tendons and More Damaged Tendons

Injuries to flexor tendons are extremely common amongst racehorses, with the deep digital flexor tendon and superficial digital flexor tendon being the most affected. These can be relatively minor lesions, which heal up quite nicely, to more serious ruptures that end a racing career.

There is always a risk of re-injury due to the weakness, and in serious cases, a second rupture could be catastrophic. It often depends on the quality of treatment and length of rest given at the time, as well as re-conditioning before returning to work.

Check for: a thicker area of the tendons indicates an old injury that has healed, while a curvature along the length of the tendon is a classic ‘bowed tendon’, sign of a far more serious injury.

7. Small but Vital: Fractures in the Fetlocks

7. Small but Vital: Fractures in the Fetlocks

Fetlocks are vulnerable due to hyper-extension, when the back of the fetlock comes too close to the ground when all the weight is borne on one foreleg at high speeds. Extremely high forces occur at the back of the fetlock and pastern as the horse lands the forefoot. Poor hoofcare, in the form of ‘low heel, long toe’ imbalance, also plays a significant part in this.

With fractures, the big, big issue is the type and location. A damaged sesamoid (the two small bones at the back of the fetlocks are the sesamoids)can play havoc with the vital suspensory ligament. So if you see signs of a problem, you’ll always need to know more, and that will usually mean involving a vet.

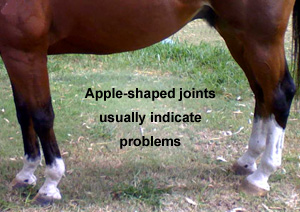

Check for: Sesamoid fractures will show up as ‘over-rounded’ or ‘apple shaped’ fetlocks, where swelling from an old injury has disrupted the joint capsule and/or extra calcium has formed around a restricted joint. Are the fetlocks of the forelegs the same size and shape? If one joint is larger and rounder, or if the ligament at the back of the foot feels thicker, with puffiness above the back of the fetlock, be suspicious.

Original article by Jane Clothier, www.thehorsesback.com posted 9 Feb 2014. All text and photographs (c) Jane Clothier. No reproduction without permission, sorry.

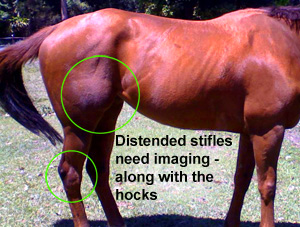

8. The Stifles Cop It, Nearly Every Time

8. The Stifles Cop It, Nearly Every Time

There are numerous causes for stifle issues in ex-racehorses, but you can take the view that if there’s a problem anywhere in the hindquarters, the stifle usually suffers. This includes any pelvic imbalance that leads to unequal loading of the hind limbs, never mind the forces of running on a unilateral bend…

Then there are the rotational twists that can happen in collisions and on bad ground. There are so many ligaments around this complex double joint that it really isn’t hard for it to get compromised.

Check for: A regular click as a hind leg starts to swing forward. This is the patellar momentarily catching, which can happens due to the lateral imbalance (causing misalignment in the femeropatellar joint). Other signs are visual: distension (swelling) of the joint may be visible from the side-on view, or from the front looking back towards the tail, depending on which part of the joint has been affected (femeropatellar or femerotibial).

9. Bringing up the Rear: Hocks Are Vulnerable Too

9. Bringing up the Rear: Hocks Are Vulnerable Too

The hock comes under major stress due to being so involved in providing propulsive power in the gallop. As a major hinge joint, it is central to jumping out of starting gates/barriers, when it’s subject to the load of almost the entire horse. In the gallop, it must alternate between being compressed to absorb concussion, being rigid to build energy, and then extending fully to dispel energy and move the horse forwards.

Frequently, it’s doing this while subject to uneven loading on a bend. Then there are the unplanned twists and traumas. Well-conformed hocks may deal with this pretty well, but over-straight hocks and ‘cow hocks’ mean that the joint is less able to withstand high levels of work. It’s common for DJD to develop in the lower bones of the joint, especially on the side that’s on the inside of the bend the horse raced in.

Check for: look for puffiness on the face of the joint. Also look for bog spavins – these are specific fluid bumps on the front of the joint, which indicate underlying issues. Bone spavins are their bony equivalents, being hard bumps lower on the face of the joint, which indicate the presence of established DJD (arthritis). Also, listen for a crunching noise or a crack when the hind foot is lifted.

10. A Crash and Bang on the Shoulder

10. A Crash and Bang on the Shoulder

Racehorses can experience awkward impacts at the base of the neck, above the point of the shoulder. It can happen when bunched-up horses collide or run against railings, during a fall, or through everyday routine, such as a severe knock against a stable door. One outcome can be damage to the supraspinous nerve, which runs over the face of the shoulder blade (scapula).

When damaged, this can lead to wasting or even paralysis of the muscles over the shoulder blade itself, which is a problem, because these muscles stabilise the shoulder joint. This condition is known as ‘sweeney’. Mild cases usually recover, but more severe cases can be left with permanently wasted muscles. With reduced function in one shoulder and a shortened stride, the horse won’t be suited to demanding sports.

Check for: a lack of muscle over the shoulder blade itself. This is more than just tight muscles – the spine of the shoulder blade will be visually obvious and easy to identify through touch.

And There’s More… There’s Always More

It’s hard to know where to stop with an article like this, but I hope this is a good start when it comes to assessing a horse. You may be thinking that many of the problems are those you should check for in any new horse purchase – and you’d be right. However, anyone who works regularly with ex-racehorses will recognize that there are certain sets of issues that come with these former athletes.

It’s hard to know where to stop with an article like this, but I hope this is a good start when it comes to assessing a horse. You may be thinking that many of the problems are those you should check for in any new horse purchase – and you’d be right. However, anyone who works regularly with ex-racehorses will recognize that there are certain sets of issues that come with these former athletes.

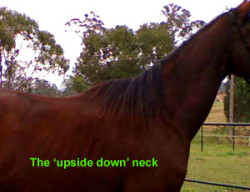

What I haven’t covered: neck issues are common (calcification at the top of the nuchal ligament, misshapen atlas and atlanto-occiptal junction, etc), hidden stress fractures (radius and tibia are most common, but also the scapula… and others), the fractured ribs that come with sideways impacts in a race, misalignment through C6-T4, and quite a few more… but all are harder for the non-professional to assess.

Other information is more of interest to people working in the field. For this reason, I’m adding some links below. Please feel free to mention your own in the Comments…

To finish off, here are two horses that raced in Australia, where it’s common to train horses at the very racetrack where they run most of their races. In the state of NSW, the horses run clockwise (the bay), while in the state of Victoria, they run anti-clockwise (the chestnut). A view straight down the ‘unstraight’ spine can tell you so much!

Has this Article Helped with your Thoroughbred?

If so, you can help me to help horses by making a one-off Paypal donation towards the site’s running costs.

Now check out this article OTTB rehabilitation: 8 Golden Rules For Helping Your Thoroughbred Get Right Off The Track

Questions, thoughts or comments? Join us at The Horse’s Back Facebook Group.