Were you around when your horse was born? If so, you’ll know about their neonatal health. If you weren’t, then understandably you don’t.

Your horse could have been a premature or dysmature foal and you might never, ever know.

Why is this a problem?

Well, anyone who’s been around me or reading my posts here over recent years will know that I’ve been researching the developmental issues experienced by premature and dysmature foals – or more specifically, the problems they carry forward into adulthood.

It’s an under-researched area, but I made some headway. Last year I was awarded my PhD for Beyond the Miracle Foal: A Study into the Persistent Effects of Gestational Immaturity In Horses.

It’s an under-researched area, but I made some headway. Last year I was awarded my PhD for Beyond the Miracle Foal: A Study into the Persistent Effects of Gestational Immaturity In Horses.

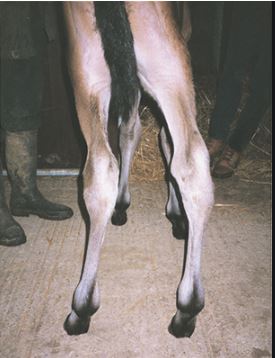

In my thesis, I included studies that showed some of the lasting developmental effects in some (not all) horses with a history of prematurity or dysmaturity at birth. (Many twins are dysmature, by the way. Fascinatingly cute, but frequently devastatingly dysmature.)

You see, a lot of gestationally immature foals don’t just ‘get over it’, catch up and become exactly the same as they would have been had they not had problematic gestations. Some do, but many don’t.

Here’s the lowdown from my own research – which I’m convinced is the tip of the iceberg.

© All text copyright of the author, Jane Clothier, https://thehorsesback.com. No reproduction of partial or entire text without permission. Sharing the link back to this page is fine. Please contact me for more information. Thank you!

Changes Linked to Prematurity and Dysmaturity

Conformation

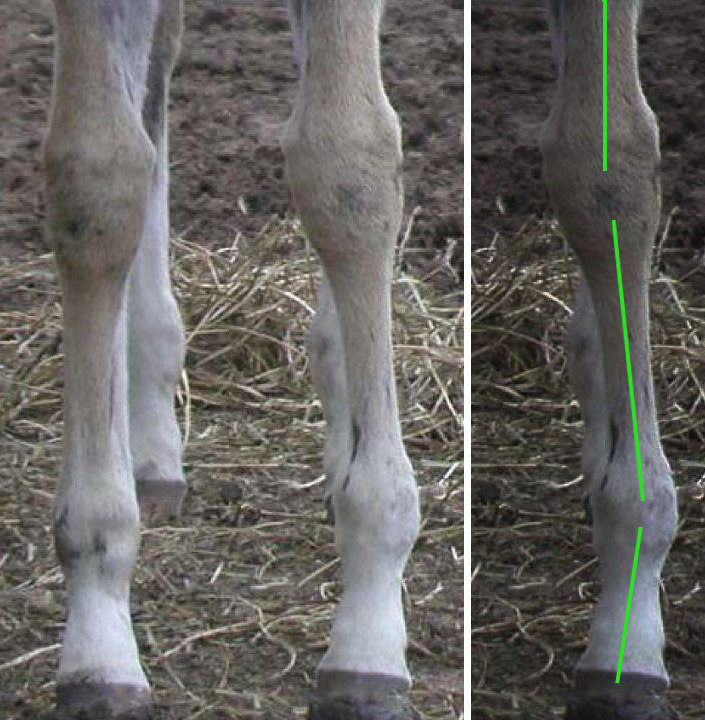

Physically, they tend to have restricted distal limb growth and a more ‘rectangular’ conformation. I’ve published a paper on this in the peer reviewed journal, Journal of Equine Veterinary Science (JEVS).

Behavior

Owners indicated in a survey that affected horses tended to be more aggressive, active, intolerant and untrusting than closely related horses. This was more evident in the so-called ‘hotter’ breeds and in mares (no surprise on two counts there!).

Orthopedic issues

Orthopedic issues

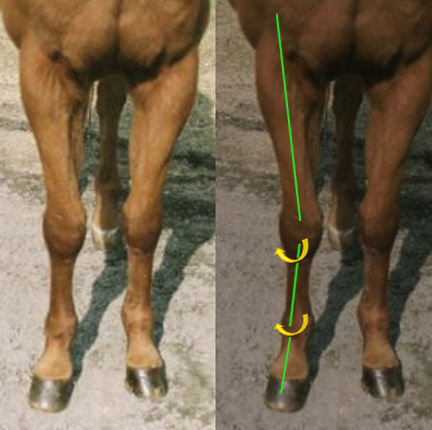

Angular limb deformities, a fairly common orthopaedic issue, can adversely affect these horses’ recumbent rest. This means that they find it harder to rest for the typical 20-30 minute bouts, a fact that could adversely affect valuable REM sleep. Again, I’ve published on this subject in JEVS.

Stress responses

When a low dose ACTH challenge was administered, these horses presented a lowered or heightened salivary cortisol response. In other words, they have a different adrenocortical response to stress to closely related horses. As the adrenalin and cortisol ratios are affected, they may stay stressed for longer after a stress event. Different stress responses can affect health, learning, training, and quality of life.

Developmental Programming

There’s more – a lot more. This is part of what’s known as Developmental Programming, or the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD).

There’s more – a lot more. This is part of what’s known as Developmental Programming, or the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD).

Previous researchers have established disorders including:

- differences in hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function,

- differences in pancreatic beta-cell function, and

- glucose metabolism, plus

- effects due to neonatal stress in pony foals (and clearly, weak or premature foals may experience neonatal stress, whether they are ill or not).

Don’t understand that? It doesn’t matter. All you need to know is that these studies already point towards pathologies such as kidney disease and Equine Metabolic Syndrome, plus a different physiological responses to stressors.

A Syndrome of Gestational Immaturity

In my view, there is definitely a Syndrome of Gestational Immaturity in horses.

By the way, gestation length on its own isn’t a good indicator of how badly a foal is affected, unless they’re extremely premature (here’s my paper on gestation length variability in the Australian Veterinary Journal).

There’s a wide range of possible problems – some horses have some of them, other horses have others, and some have none at all. They’re individuals, while everything else in their experience and care makes a difference too.

There’s a wide range of possible problems – some horses have some of them, other horses have others, and some have none at all. They’re individuals, while everything else in their experience and care makes a difference too.

That’s how it is with syndromes. And right now, it’s all flying completely under the radar.

These are silent problems that are only recognized when they rear their proverbial ugly heads further down the line – if they are recognized at all. My heart aches for these horses and ponies, for many do not find life easy.

(c) Jane Clothier, The Horse’s Back.

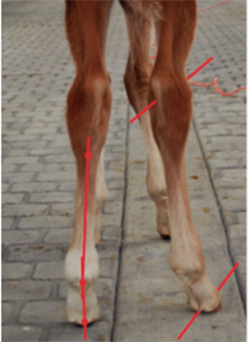

What we’re looking at is a combination of ALDs: carpal valgus and varus in front, and/or a tarsal valgus and varus behind.

What we’re looking at is a combination of ALDs: carpal valgus and varus in front, and/or a tarsal valgus and varus behind.

There’s a basic premise of saddle fitting that hasn’t occurred to a lot of people. It can’t have done, not if the tack they’re riding in is anything to go by.

There’s a basic premise of saddle fitting that hasn’t occurred to a lot of people. It can’t have done, not if the tack they’re riding in is anything to go by. The reason for this statement is simply to highlight the fact that inserting a relatively static piece of equipment between two living organisms in motion is, at best, always going to be fraught with complexity.

The reason for this statement is simply to highlight the fact that inserting a relatively static piece of equipment between two living organisms in motion is, at best, always going to be fraught with complexity.