This Diploma is open to experienced equine therapists, physiotherapists and chiropractors and animal care professionals such as trainers, vet techs, breeders, trainers, and farriers.

The past decade has seen an explosion in hands-on equine therapies, with an unprecedented number of courses in musculoskeletal therapies appearing.

There are surely more equine bodyworkers than ever before. It’s a competitive world out there for therapists!

Perhaps, like many, you’ve found there’s a ceiling on the level of training you can access.

You may be adept at working with the soft tissue structures of the horse’s body, yet when it comes to addressing deeper structural concerns, you’re sometimes at the limits of your skills.

Thankfully, there’s now an opportunity to dramatically raise your knowledge and skills, while gaining the professional edge in your mission to help horses.

Introducing The International Diploma in Equine Osteopathy

Receive 45-50 % OFF by using the links on this page and clicking the Horse’s Back when you apply!

International leader in animal osteopathic education, the London College of Animal Osteopathy (LCAO), has recently launched one of the highest levels of training currently available outside universities.

The International Diploma in Equine Osteopathy (Int’l DipEO) is led by LCAO founder and renowned osteopath Professor Stuart McGregror, D.O., who shares the knowledge and techniques he has taught internationally since 1998.

OFFER: 40% Off All Programs

Equine program regular fee: US $3,800 With 40% off: US $2,280

Unlock another 5-10% discount by mentioning The Horse’s Back when you apply.

The Osteopathic Knowledge You’ll Gain

It’s the perfect balance of theory and practice

Drawing on 30 years’ experience of teaching equine osteopathy, Stuart will instruct in the following areas, building your capacity as a therapist.

- Understand the systemic and functional anatomy, physiology, and biomechanics of the horse.

- Learn how to perform performing a physical examination using observation, palpation skills, and clinical reasoning skills.

- Be able to deliver an effective treatment using appropriate osteopathic techniques.

- Recognize indications and contraindications to osteopathic treatment.

- Understand your role as an osteopath within today’s animal health care model.

- Understand the osteopathic philosophy and principles as applied to horses.

- Understand the osteopathic approach to health and disease based on structure-function models.

OFFER: 40% Off All Programs

Unlock another 5-10% discount by mentioning The Horse’s Back when you apply.

Helping Horses with Equine Osteopathy

How you can become a more effective practitioner

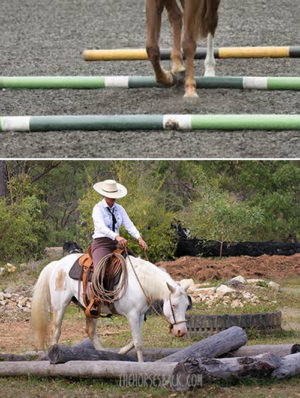

Stuart will teach you a general osteopathic treatment with its roots deep in classical osteopathy. Called Osteopathic Articular Balancing (OAB), it improves the horse’s function by relieving pain, maximizing movement, and increasing performance.

As a gentle manipulation of the whole body, OAB removes tensions and restrictions, restoring health through the assessment and treatment of muscles, joints, tendons, and ligaments.

“One of the main principles in osteopathic medicine is that treatment should restore health to the local tissues. This involves the restoration of blood supply, nerve supply, and lymphatic drainage. Where any of these are absent, the tissues can only be in poor health.” – Stuart McGregor

Unlock another 5-10% discount by mentioning The Horse’s Back when you apply.

Learn Better Assessment and Treatment of Horses

Treat with more effective skills

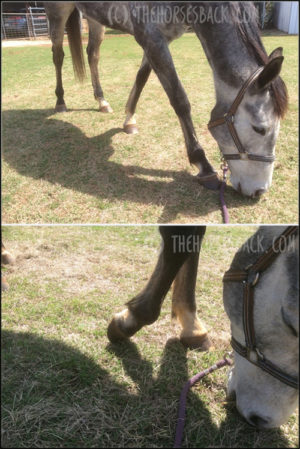

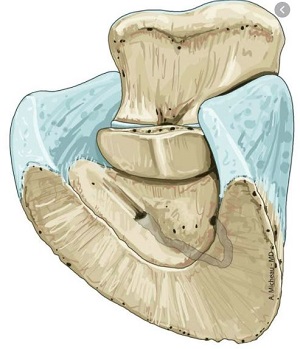

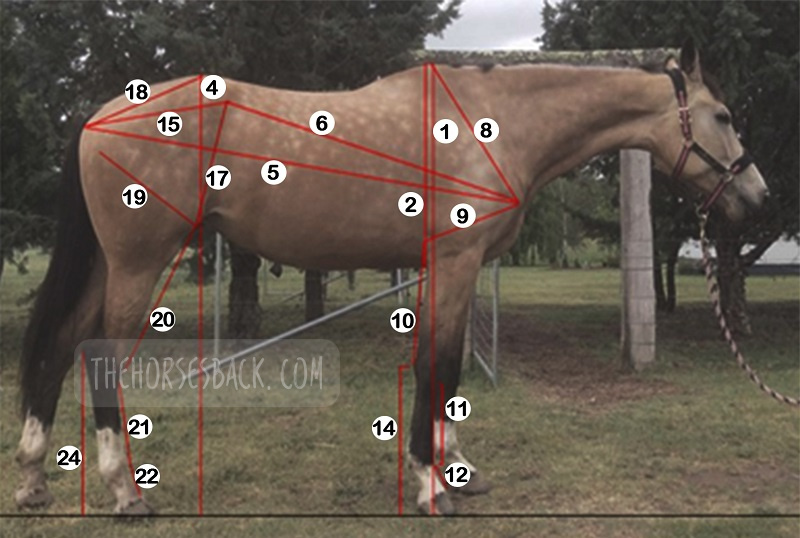

Putting OAB into practice with the horse, you’ll examine the functional anatomy of each joint and its accompanying structures.

You’ll also consider the direct and indirect relationships that extend through the skeletal system, taking in posture, gait assessment, and palpation.

Next, you’ll mobilize associated bones using the ‘functional’ osteopathic techniques taught by Stuart. These are gentle, slow and small controlled movements, as opposed to high velocity, short lever thrusts.

OFFER: 40% Off All Programs

Unlock another 5-10% discount by mentioning The Horse’s Back when you apply.

Learn a Truly Holistic Approach…

Explore the many factors affecting horses’ bodies

Besides treating the horse’s whole body with equine osteopathy, you’ll learn how to bring other considerations and assessments into your treatment approach. You’ll be learning about:

- The effect of gravity and rider weight on the vertebral column and pelvis.

- Pathologies associated with specific sports.

- The differences in the functions of hindlimbs and forelimbs.

- A range of congenital and developmental conditions.

- Various health issues.

- Incorrect riding.

- Poorly fitting tack.

- Inferior hoof balance.

- Dental issues.

- Behavior.

My Personal Experience

I only write posts on this blog about subjects I believe in. I have personal experience of Prof McGregor’s equine osteopathy training, having organised his first course for equine therapists in Australia – this program includes techniques that I use with every horse I see.

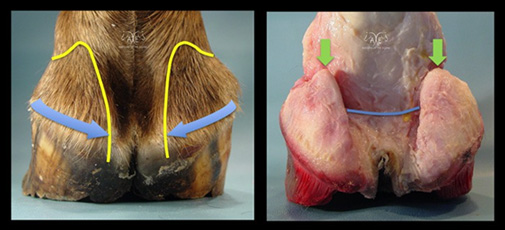

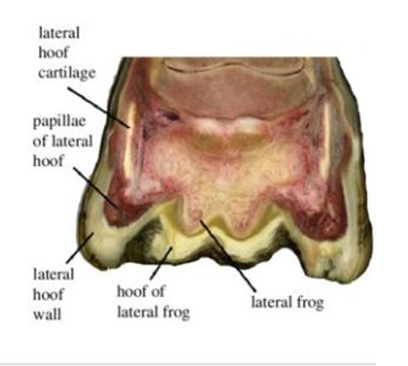

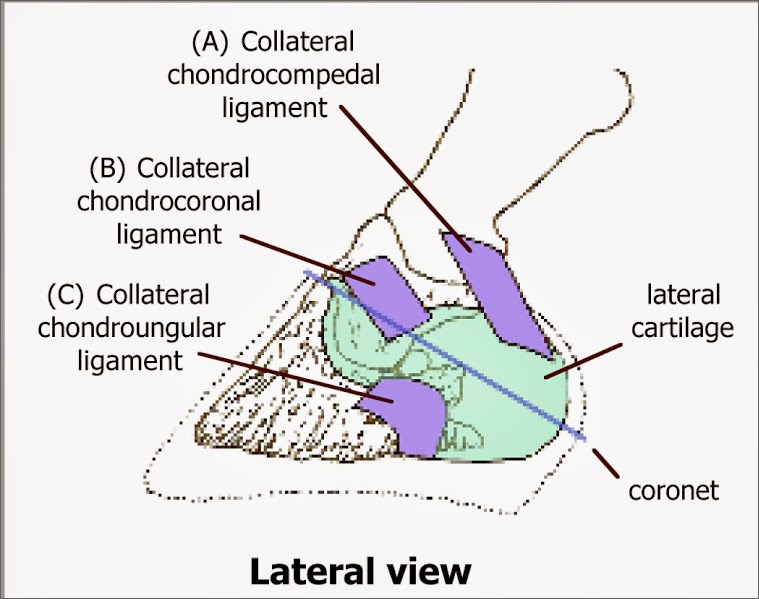

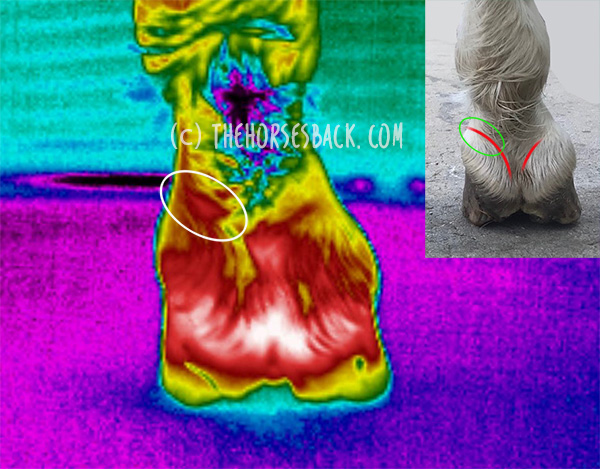

In fact, I used these techniques when first assessing the lateral cartilages explored in this article: Beyond Sidebone: Pastern Pain and the Lateral Cartilage.

Prof McGregor is also very supportive of this blog. For these reasons, we’re offering an extremely generous discount to anyone who books via this page.

These links will save you up to 50% (seriously!), while this blog receives a benefit that helps to cover my considerable writing time and publication costs.

Are You Ready for 1,000 Hours of Equine Osteopathy Training?

It’s fascinating and deeply rewarding!

This training will help you to develop as an effective practitioner with the knowledge and skills to truly help horses.

To qualify, you’ll need to complete at least 1,000 hours of core knowledge and clinical learning. You’ll submit written and video asssessments, and a thesis, and take an elective class in advanced clinical skills – available in Europe, the US or Australia.

As an equine professional, you’ll expand your practice and develop treatment styles relevant to your current practice, through:

- Pre-clinical studies to build your core knowledge (500 hours).

- Clinical studies, guiding you through osteopathic research (500 hours).

- Advanced masterclass, with hands-on clinical training in advanced modalities such as cranial osteopathy, short lever and functional techniques.

- Individual tutoring sessions.

- Open group discussions.

OFFER: 40% Off All Programs

Unlock another 5-10% discount by mentioning The Horse’s Back when you apply.

Education That Suits Your Lifestyle

Benefit from this flexible program

You can study for the International Diploma in Equine Osteopathy in a way that suits you.

Most of the content is delivered through recorded lectures, video tutorials, downloadable presentations, digital textbooks, and additional readings.

This means you can work at your own pace, at times of the day that work for you.

But you’re never alone with your study, for you can constantly connect with your course instructor and student forum.

This means that you can complete in your own time and, best of all, benefit from lifetime access to the online resources.

The LCAO uses a best practice model derived from the academic programs of higher education institutes, with an eLearning platform powered by Moodle software.

Who Can Apply?

The International Diploma of Equine Osteopathy is open only to approved therapists and animal care professionals

As not everyone can take this qualification, you need to apply to be admitted. The LCAO will consider applications from:

- DVMs, VMDs, animal physiotherapists and chiropractors

- Osteopaths and osteoapthic manual therapists (OMTs)

- Registered MSK practitioners, ie massage therapists, osteopathic manual therapists

- Veterinary technicians, nurses and assistants

- Equine bodywork therapists with 7+ years of experience

- Equine professionals with 7+ years of experience, eg trainers, breeders, farriers, equine massage therapists and bodyworkers, yard managers

- Graduates and students of animal science degree programs

Download the prospectus to learn more, or apply straightaway.

More About Prof Stuart McGregor, D.O.

Stuart McGregor has taught hundreds of animal osteopaths over a period of some 30 years.

He graduated from the UK’s European School of Osteopathy in 1984, having completed his dissertation on The Principles of Osteopathy Applied to the Horse. This was the first known work about osteopathy for horses.

He soon began treating horses and dogs, and it was not long before he set up the Osteopathy Centre for Animals in Oxfordshire, England.

Other osteopaths and veterinarians soon came across his work and were keen to learn more, so in 1998 he began to teach. Since that time he has refined his methods and instruction, leading to the training that he practices and teaches today.

“In our treatment, there is something we call ‘intent’. This is where we apply the techniques intending to enable healing. We imagine ourselves inside the tissues being treated and then bring about positive change.” – Stuart McGregor

OFFER: 40% Off All Programs

Equine program regular fee: US $3,800 With 40% off: US $2,280

Unlock another 5-10% discount by mentioning The Horse’s Back when you apply.

Treat Horses and Dogs with the LCAO

If you’re keen to expand your practice to include both horses and dogs, you may be interested in the Animal Osteopathy qualifications, which address both species.

- International Diploma in Equine Osteopathy (Int’l DipEO)

- International Diploma in Animal Osteopathy (Int’l DipAO)

- International Diploma in Canine Osteopathy (Int’l DipCO)

For licensed veterinarians (DVM/VMD) and final year students of veterinary programs, LCAO also offers the following postgrad programs:

- Postgraduate Diploma in Equine Osteopathy (PGDipEO)

- Postgraduate Diploma in Animal Osteopathy (PGDipAO)

- Postgraduate Diploma in Canine Osteopathy (PGDipCO)

Here are abstracts, downloads and links for my research into the ongoing effects or premature or dysmature birth in horses.

Here are abstracts, downloads and links for my research into the ongoing effects or premature or dysmature birth in horses. Breeding horses can be a financially and emotionally expensive undertaking, particularly when a foal is born prematurely, or full term but dysmature, showing signs normally associated with prematurity. In humans, a syndrome of gestational immaturity is now emerging, with associated long-term sequelae, including metabolic syndrome, growth abnormalities and behavioural problems.

Breeding horses can be a financially and emotionally expensive undertaking, particularly when a foal is born prematurely, or full term but dysmature, showing signs normally associated with prematurity. In humans, a syndrome of gestational immaturity is now emerging, with associated long-term sequelae, including metabolic syndrome, growth abnormalities and behavioural problems. Clear definitions of ‘normal’ equine gestation length (GL) are elusive, with GL being subject to a considerable number of internal and external variables that have confounded interpretation and estimation of GL for over 50 years. Consequently, the mean GL of 340 days first established by Rossdale in 1967 for Thoroughbred horses in northern Europe continues to be the benchmark value referenced by veterinarians, breeders and researchers worldwide. Application of a 95% confidence limit to reported GL range values indicates a possible connection between geographic location and GL.

Clear definitions of ‘normal’ equine gestation length (GL) are elusive, with GL being subject to a considerable number of internal and external variables that have confounded interpretation and estimation of GL for over 50 years. Consequently, the mean GL of 340 days first established by Rossdale in 1967 for Thoroughbred horses in northern Europe continues to be the benchmark value referenced by veterinarians, breeders and researchers worldwide. Application of a 95% confidence limit to reported GL range values indicates a possible connection between geographic location and GL. Chronic musculoskeletal pathologies are common in horses, however, identifying related effects can be challenging. This study tested the hypothesis that movement sensors and analgesics could be used in combination to confirm the presence of restrictive pathologies by assessing lying time. Four horses presenting a range of angular limb deformities (ALDs) and four non-affected controls were used.

Chronic musculoskeletal pathologies are common in horses, however, identifying related effects can be challenging. This study tested the hypothesis that movement sensors and analgesics could be used in combination to confirm the presence of restrictive pathologies by assessing lying time. Four horses presenting a range of angular limb deformities (ALDs) and four non-affected controls were used. The long-term effects of gestational immaturity in the premature (defined as < 320 days gestation) and dysmature (normal term but showing some signs of prematurity) foal have not been thoroughly investigated. Studies have reported that a high percentage of gestationally immature foals with related orthopedic issues such as incomplete ossification may fail to fulfill their intended athletic purpose, particularly in Thoroughbred racing. In humans, premature birth is associated with shorter stature at maturity and variations in anatomical ratios, linked to alterations in metabolism and timing of physeal closure in the long bones.

The long-term effects of gestational immaturity in the premature (defined as < 320 days gestation) and dysmature (normal term but showing some signs of prematurity) foal have not been thoroughly investigated. Studies have reported that a high percentage of gestationally immature foals with related orthopedic issues such as incomplete ossification may fail to fulfill their intended athletic purpose, particularly in Thoroughbred racing. In humans, premature birth is associated with shorter stature at maturity and variations in anatomical ratios, linked to alterations in metabolism and timing of physeal closure in the long bones.

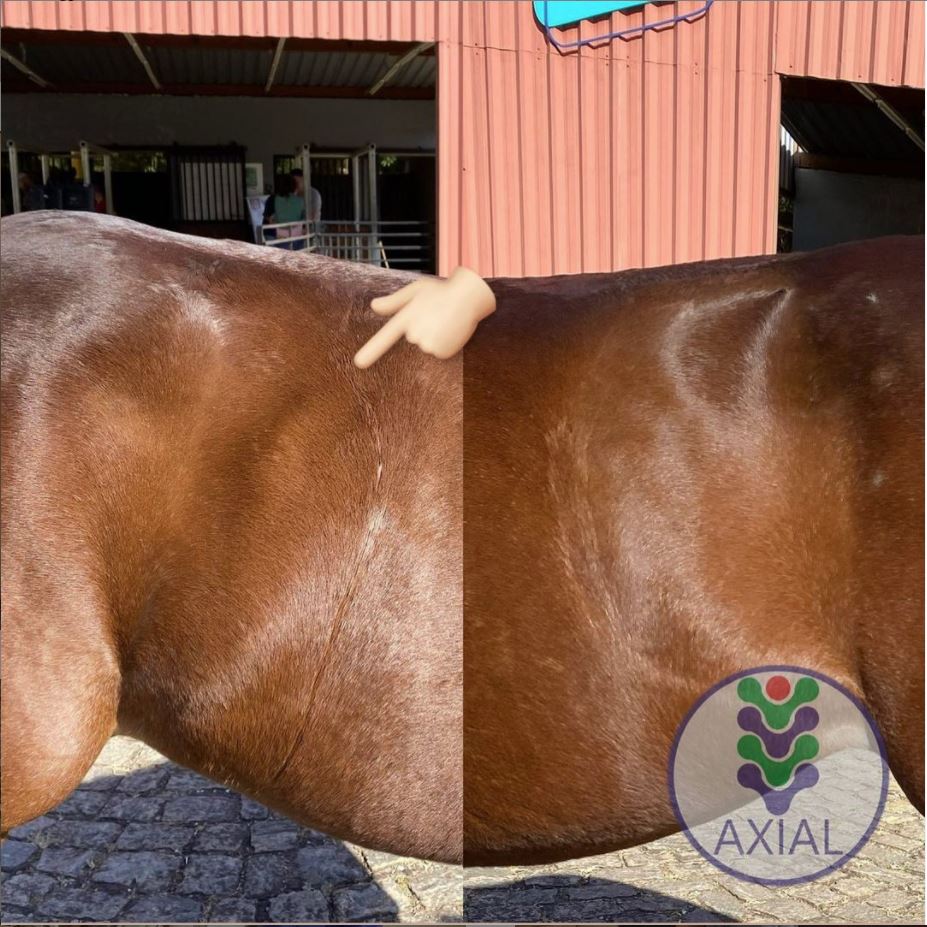

Meet Dr Brunna Fonseca, Associate Professor, educator and specialist in equine orthopedics, focusing on the spine and nervous system. She’s based in S

Meet Dr Brunna Fonseca, Associate Professor, educator and specialist in equine orthopedics, focusing on the spine and nervous system. She’s based in S

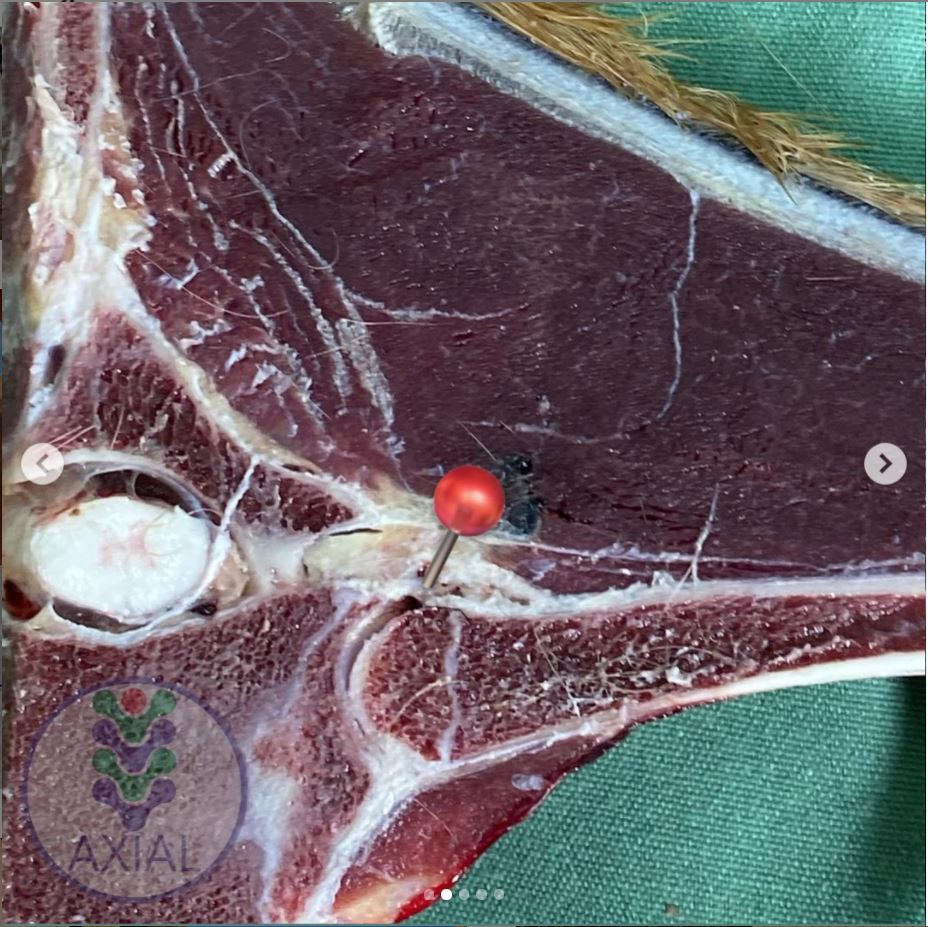

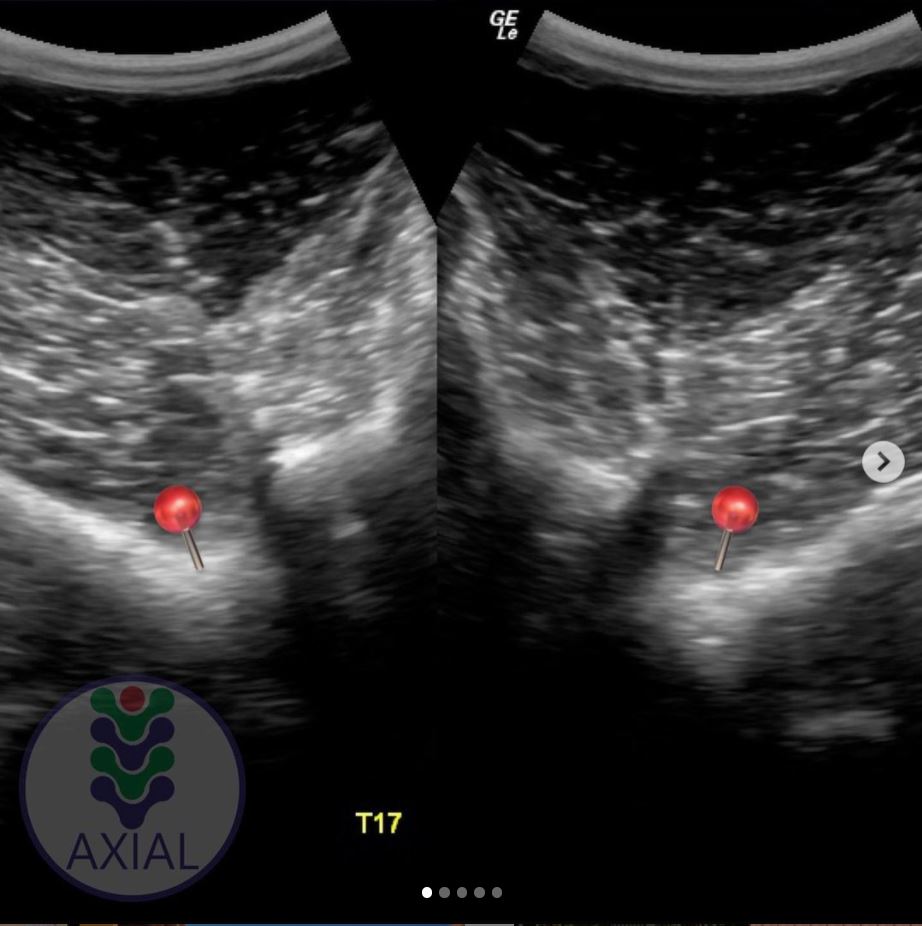

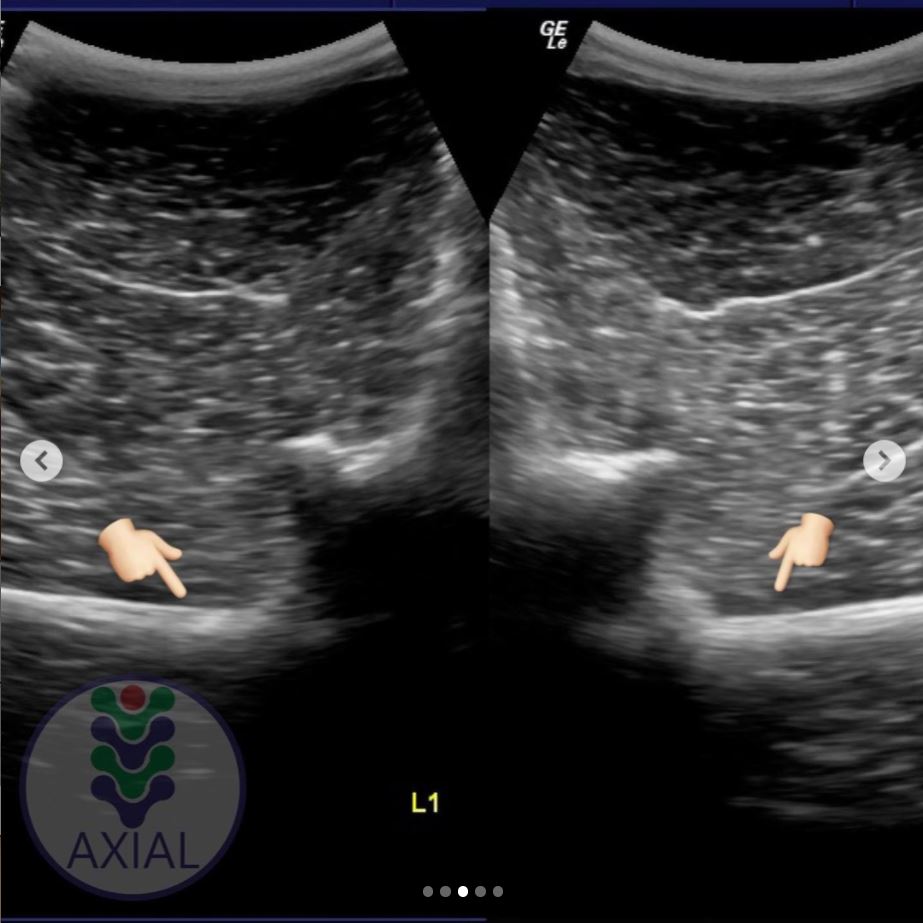

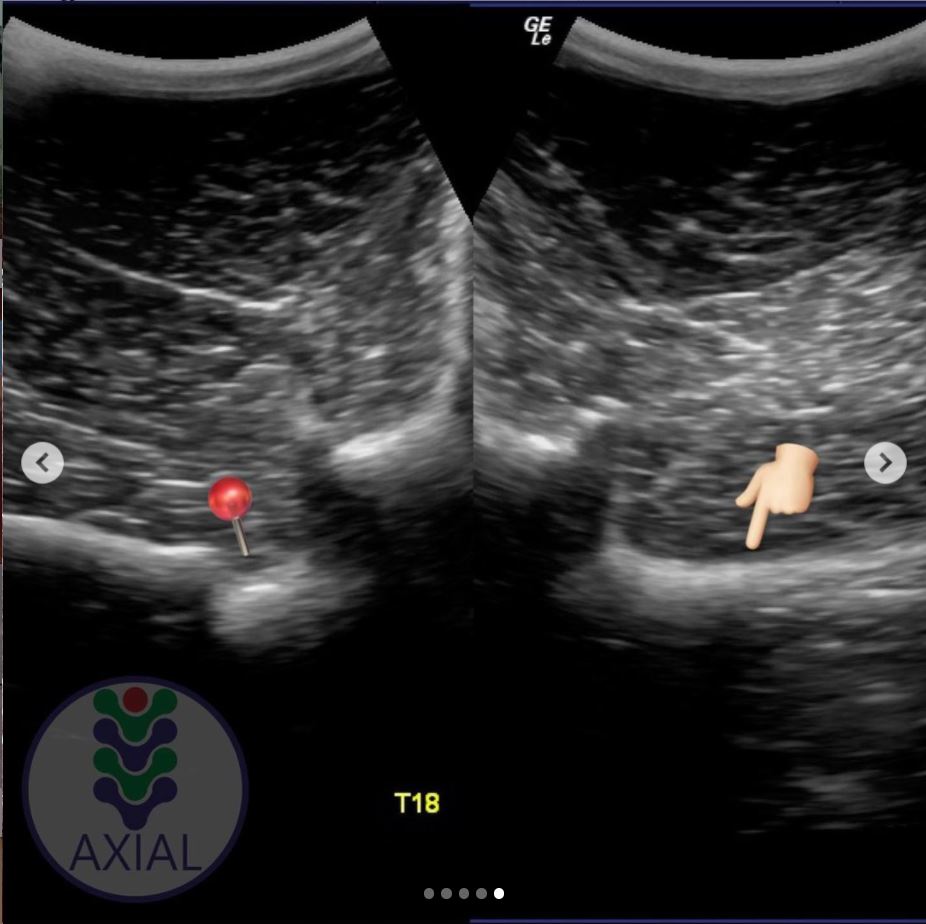

6. Imaging transitional vertebrae

6. Imaging transitional vertebrae You can follow her

You can follow her

Tension also builds because the horse is trying – and failing – to balance their weight centrally.

Tension also builds because the horse is trying – and failing – to balance their weight centrally.