It’s barely mentioned in saddle fit or anatomy books, yet the muscle Spinalis cervicis can hugely impact on the spinal health and movement of the horse, particularly with poor tack fit.

Meet muscle Spinalis cervicis et thoracis, a far more important muscle than is generally realized. As a deep muscle, it’s influential in mobilizing and stabilizing that hidden area of the spine at the base of the neck, the cervico-thoracic junction, deep between the scapulae.

Where to Find this Muscle

As part of the deeper musculature, Spinalis is as hidden in books as it is in life. Usually, it’s a single entry in the index.

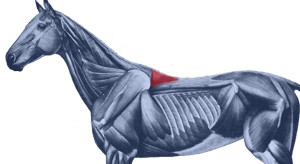

At best, it has no more than a bit part in anatomical illustrations, usually as a small triangular area at the base of the withers. This is also where we can palpate it.

At best, it has no more than a bit part in anatomical illustrations, usually as a small triangular area at the base of the withers. This is also where we can palpate it.

The reality is quite a bit more interesting. It’s actually a muscle of three parts – dorsalis, thoracis and cervicis. These names denote its many insertions, for it links the spinous processes of the lumbar, thoracic and cervical vertebrae.

Further back along the spine, it lies medially to Longissimus dorsi, and in fact integrates with this larger, better known muscle, attaching to the processes of the lumbar and thoracic vertebrae.

Further back along the spine, it lies medially to Longissimus dorsi, and in fact integrates with this larger, better known muscle, attaching to the processes of the lumbar and thoracic vertebrae.

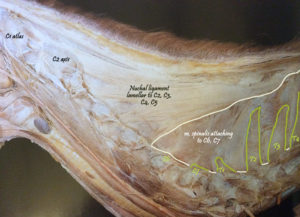

- When it reaches the withers, it becomes more independent, attaching to the processes of the first half dozen thoracic vertebrae (T1-T6). Here, the cervical and thoracic portions overlap and integrate to share a common attachment. (The part we palpate, at the base of the withers, is the thoracic section.)

- Heading into the neck, as Spinalis cervicis, it attches to the last 4 or 5 cervical vertebrae (C3/C4-C7). Only the lamellar portion of the nuchal ligament runs deeper than this muscle.

Its integration with other muscles is complex, and its close relationship with Longissimus dorsi partially explains why it doesn’t get much consideration as a muscle in its own right.

Its integration with other muscles is complex, and its close relationship with Longissimus dorsi partially explains why it doesn’t get much consideration as a muscle in its own right.

It is the more independent section, Spinalis cervicis, between withers and neck, that we are interested in, although its influence is present along the entire spine.

© All text copyright of the author, Jane Clothier, https://thehorsesback.com.

What Does Spinalis Do?

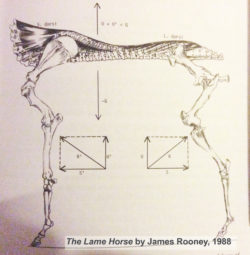

In his 1980s’ Guide to Lameness videos, Dr. James Rooney, first director of the Gluck Equine Research Center, University of Kentucky, referred to Spinalis as part of the suspension bridge of muscles supporting the spine (Longissimus dorsi achoring from the lumbosacral vertebrae, Spinalis thoracis et dorsalis from the upper thoracics). He also refers to this extensively in The Lame Horse (1988).

In his 1980s’ Guide to Lameness videos, Dr. James Rooney, first director of the Gluck Equine Research Center, University of Kentucky, referred to Spinalis as part of the suspension bridge of muscles supporting the spine (Longissimus dorsi achoring from the lumbosacral vertebrae, Spinalis thoracis et dorsalis from the upper thoracics). He also refers to this extensively in The Lame Horse (1988).

In fact, the suspension bridge analogy only really makes sense if Spinalis dorsi is considered.

Spinalis cervicis is usually credited with a role in turning the head to left to right, and raising the head.

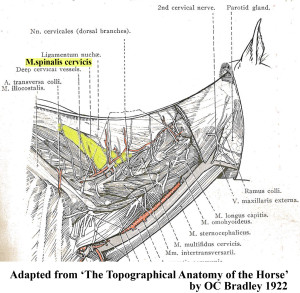

Older texts, such as Bradley’s 1922 veterinary dissection guide, Topographical Anatomy of the Horse, mention its role in stabilizing the spine.

Older texts, such as Bradley’s 1922 veterinary dissection guide, Topographical Anatomy of the Horse, mention its role in stabilizing the spine.

This creates a point of interest. Given that the nuchal ligament (lamellar portion) doesn’t attach to C6 and frequently only weakly with C5 (see the findings of anatomist Sharon May-Davis, in this earlier article ), Spinalis cervicis suddenly appears pretty important in stabilizing and lifting the base of the neck, particularly as it does so at the point of greatest lateral bending.

Spinalis and Poor Saddle Fit

Anyone who has been involved in close examination of the horse’s back will recognize Spinalis thoracis where it surfaces close to the skin, on either side of the withers.

When a horse has been ridden in an overly tight saddle, this small area of muscle can become pretty hypertrophic – raised and hardened. Typically, the neighbouring muscles are atrophied. When Spinalis is palpated, the horse often gives an intense pain response, flinching down and raising the head.

What often happens is this. An overtight saddle fits over the base of the withers like a clothes peg, pinching Trapezius thoracis and Longissimus dorsi. However, it frequently misses Spinalis thoracis where it surfaces, wholly or partially within the gullet space. Often, the muscle is partially affected.

What often happens is this. An overtight saddle fits over the base of the withers like a clothes peg, pinching Trapezius thoracis and Longissimus dorsi. However, it frequently misses Spinalis thoracis where it surfaces, wholly or partially within the gullet space. Often, the muscle is partially affected.

It’s as if the neighbouring muscles are under lockdown. Free movement of the shoulder is restricted and the horse’s ability to bear weight efficiently while moving is impeded. In response to the surrounding restriction and its own limitation, this muscle starts to overwork.

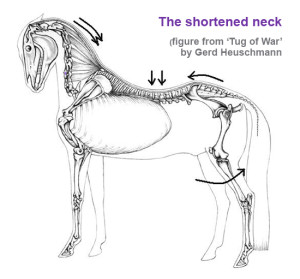

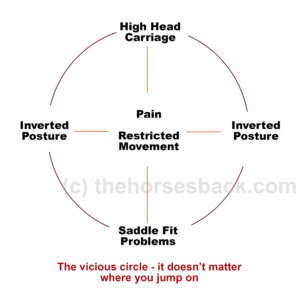

Result? The horse, which was probably already moving with an incorrect posture, hollows its back even further, shortening the neck and raising its head. As this becomes even more of a biomechanical necessity, all the muscles work even harder to maintain this ability to move, despite the compromised biomechanics.

Working harder and compensating for its neighbours, Spinalis becomes hypertrophic. It is doing what it was designed to do, but it’s now overdoing it and failing to release. We now have a rather nasty vicious circle.

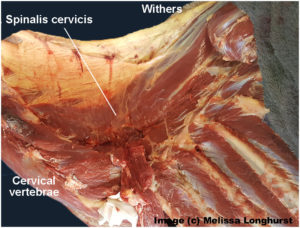

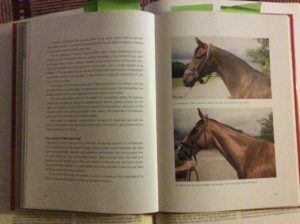

Here, Spinalis thoracis stands out due to atrophy of the surrounding musculature. In this TB, a clearly audible adjustment occurred in the C4-C5 area after the muscle was addressed.

The Inverted Posture and Asymmetry

The Inverted Posture and Asymmetry

Of course, saddle fit is not the only cause of an inverted posture. However, any horse that holds its head and neck high for natural or unnatural reasons is more vulnerable to saddle fit issues, thus starting a cascade effect of problems.

Are there further effects of this hypertrophy? Consider the connections.

- When saddles are too tight, they’re often tighter on one side than the other. This can be due to existing asymmetry in the horse, such as uneven shoulders, uneven hindquarters, scoliosis, etc.

- On the side with greater restriction, the muscle becomes more more hypertrophic.

- With its attachment to the spinous processes of the lower cervical vertebrae, there is an unequal muscular tension affecting the spine.

- Without inherent stability, the neck and head are constantly being pulled more to one side than the other, with the lower curve of the spine also affected.

- Base of neck asymmetry affects the rest of the spine in both directions and compromises the horses ability to work with straightness or elevation.

- There is also asymmetric loading into the forefeet.

- We haven’t even started looking at neurological effects…

This isn’t speculation. I have seen this pattern in horses I’ve worked on, many times over.

So, How Do We Help?

In working with saddle fit problems, the saddle refit may be enough to help the horse, if the riding is appropriate to restoring correct carriage and movement. Obviously, the horse’s musculoskeletal system is complex and no muscle can be considered in isolation. As other muscles are addressed through therapeutic training approaches, with correct lateral and vertical flexion achieved, M. spinalis will be lengthened along with the surrounding musculature.

I hold with a restorative approach:

- Refit the saddle, preferably with the help of a trained professional,

- Remedial bodywork, to support recovery from the physical damage,

- Rest the horse, to enable healing of damaged tissue and lowering of inflammation, and

- Rehabilitate the horse, through the appropriate correct training that elevates the upper thoracics while improving lateral mobility.

This is particularly important where saddle fit has been a major contributor to the problem. I have frequently found that in these cases,correction will take longer to achieve, as the debilitating effects of poor saddle fit (especially long-standing issues) can long outlast the change to a new, better-fitting saddle. In bodywork terms, the hypertrophic M. spinalis cervicis is often the last affected muscle to let go.

It’s as if Spinalis cervicis is the emergency worker who will not leave until everyone else is safe.

Bodywork Notes

I am fortunate, in that my modalities enable the gentle release of joints through a non-invasive, neuromuscular approach. The responses I’ve had from horses when M. spinalis cervicis et thoracis has been addressed in isolation have been hugely informative.

** Questions, thoughts or comments? Join us at The Horse’s Back Facebook Group.

Appendix: Spinalis in the Textbooks

I’m going to add Spinalis references to this post on a regular basis, as I come across them. It’s interesting to see how much, or how little, the muscle is referenced in various textbooks.

This image, from Equine Back Pathology, ed. F Henson 2009, shows acute atrophy of Longissimus dorsi due to neurological damage. It’s still possible to see the raised attachment/origin of Spinalis cervicis et thoracis – the highlighting is mine. Spinalis does not appear in the book’s index. (added 23 Dec 2016)

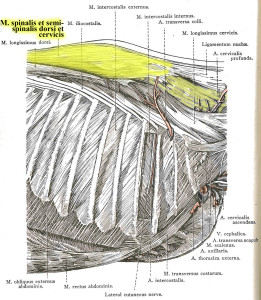

I have also altered this image, in order to show M. spinalis cervicis more clearly. This is Fig 2.16 from Colour Atlas of Veterinary Anatomy Vol 2, The Horse, R Ashdown and S Done. Spinalis cervicis is within the bounded area and it’s possible to see how it overlies the lamellar part of the nuchal ligament, lamellar portion. (added 23 Dec 2016)

I have also altered this image, in order to show M. spinalis cervicis more clearly. This is Fig 2.16 from Colour Atlas of Veterinary Anatomy Vol 2, The Horse, R Ashdown and S Done. Spinalis cervicis is within the bounded area and it’s possible to see how it overlies the lamellar part of the nuchal ligament, lamellar portion. (added 23 Dec 2016)

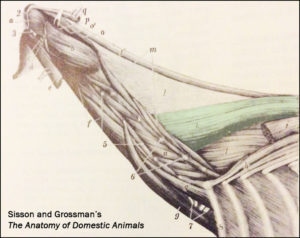

The muscle is tinted green in this image from Sisson and Grossman’s The Anatomy of Domestic Animals, Volume 1, fifth edition 1975. Here, it is labelled Spinalis et semi-spinalis cervicis. This anatomical figure is credited to an earlier text, Ellenberger and Baum, 1908. (added 23 Dec 2016)

The muscle is tinted green in this image from Sisson and Grossman’s The Anatomy of Domestic Animals, Volume 1, fifth edition 1975. Here, it is labelled Spinalis et semi-spinalis cervicis. This anatomical figure is credited to an earlier text, Ellenberger and Baum, 1908. (added 23 Dec 2016)

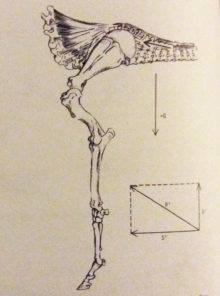

James Roony dedicates two pages to the ‘suspension bridge’ theory of the vertebral column in The Lame Horse (1988). His interest is in Spinalis dorsii section of the muscle and its effect behind the withers, in conjunction with Longissimus dorsii. (added 4 Jan 2017)

James Roony dedicates two pages to the ‘suspension bridge’ theory of the vertebral column in The Lame Horse (1988). His interest is in Spinalis dorsii section of the muscle and its effect behind the withers, in conjunction with Longissimus dorsii. (added 4 Jan 2017)

Master Saddler Jochen Schleese refers to Spinalis dorsi and its function in stabilizing the withers in Suffering in Silence, his passionate book about saddle fitting from 2014. “This muscle area is especially prone to significant development – especially with jumpers – because it is continually contracted to accommodate the shock of landing”. The surface area of the muscle is indicated in the anatomical figure, reproduced here. (added 23 Dec 2016)

Master Saddler Jochen Schleese refers to Spinalis dorsi and its function in stabilizing the withers in Suffering in Silence, his passionate book about saddle fitting from 2014. “This muscle area is especially prone to significant development – especially with jumpers – because it is continually contracted to accommodate the shock of landing”. The surface area of the muscle is indicated in the anatomical figure, reproduced here. (added 23 Dec 2016)

In his seminal text addressing issues of modern dressage training, Tug of War, 2007, Gerd Heuschmann includes Spinalis cervicis in the triangle formed by the rear of the rear of the cervical spine, the withers, and the shoulder blades, “… an extensive connection between the head-neck axis and the truck… it explains how the position and length of the horse’s neck directly affects the biomechanics of the back.” (added 31 Dec 2016)

In his seminal text addressing issues of modern dressage training, Tug of War, 2007, Gerd Heuschmann includes Spinalis cervicis in the triangle formed by the rear of the rear of the cervical spine, the withers, and the shoulder blades, “… an extensive connection between the head-neck axis and the truck… it explains how the position and length of the horse’s neck directly affects the biomechanics of the back.” (added 31 Dec 2016)