There seem to be quite a few social media posts about the equine brain of late – and that’s no bad thing.

In some ways, the brain is simply the latest part of the equine anatomy to come under the spot light. It’s being subject to statements about welfare, training and psychology – and that’s definitely a good thing (here’s one from Hippologic.)

However, I want to add something to this equine brain discussion. I just happened to run in to it when I went down a research rabbit hole a couple of years back.

We often hear how brain size is not directly linked to an individual’s intelligence. At the same time, a relatively large brain is said to signify intelligence in humans, while that of the horse, popularly said to be the size of a (large) walnut, is said to account for their lack of intelligence.

This falls down once we look at elephants, which have relatively small brains yet are pretty cluey.

In horses, innovative behaviors without evolutionary basis are often used as a measure of intelligence (read more here about unlatching gates). Leaving behaviour-based measurement methods aside for the moment, let’s ask: how do we figure out if there’s an association between different brain sizes and intelligence levels?

(Note: if you’re a neuroscientist of any description, look away now. What follows is a highly simplistic overview of this incredibly complex subject area.)

© All text copyright of the author, Jane Clothier, www.thehorsesback.com. No reproduction of partial or entire text without permission. Sharing the link back to this page is fine. Please contact me for more information. Thank you!

Measuring Equine Brain Mass and Body Mass

In zoology, the starting point isn’t about brain size, but brain mass compared with body mass or weight.

Even then, it’s not a matter of separating the brain from the body and then weighing both. The most accurate way of measuring this accounts for several anatomical, physiological factors, including the amount of water in the brain.

The result is a single figure that is called the encephalization quotient (EQ). The EQ for a species is arrived at after researchers have performed the calculation for dozens of animals.

So How Does This Look for the Equine Brain?

Only a handful of equine researchers have delved into EQs, as this is mostly an area of zoological neuroanatomy.

In this study by Cozzi et al (2014), the brains of 131 mixed breed adult horses (no ponies) were collected and weighed.[1] Researchers found first that the adult horse’s brain weighs 600 – 700 g. The average brain weight for horses aged 2 years and over was 606 g, while the average bodyweight was 535.22 kg.

This meant the horses in this study had an EQ of 0.78.

Here are the EQs for some of the large mammals: Cow – 0.55, Pig – 0.6, Camel – 0.61, Horse – 0.78, Goat – 0.8, Wolf – 0.9, Domestic Cat – 1.00, African Elephant – 1.67, Gorilla – 1.76, Human – 6.62.

And if you’re really interested, here’s the calculation used in the equine paper. Other scientists use different calculations – there is no standard approach.

EQ = E i / 0.12 P2/3Ea/Ee

So, Are Horses Intelligent – or Not?

A larger brain mass compared with body mass is often associated with better cognitive functioning, but that does not mean it causes it.

Brain size is therefore a very general measure for intelligence. What actually matters are the specific areas of the brain and their relative sizes.

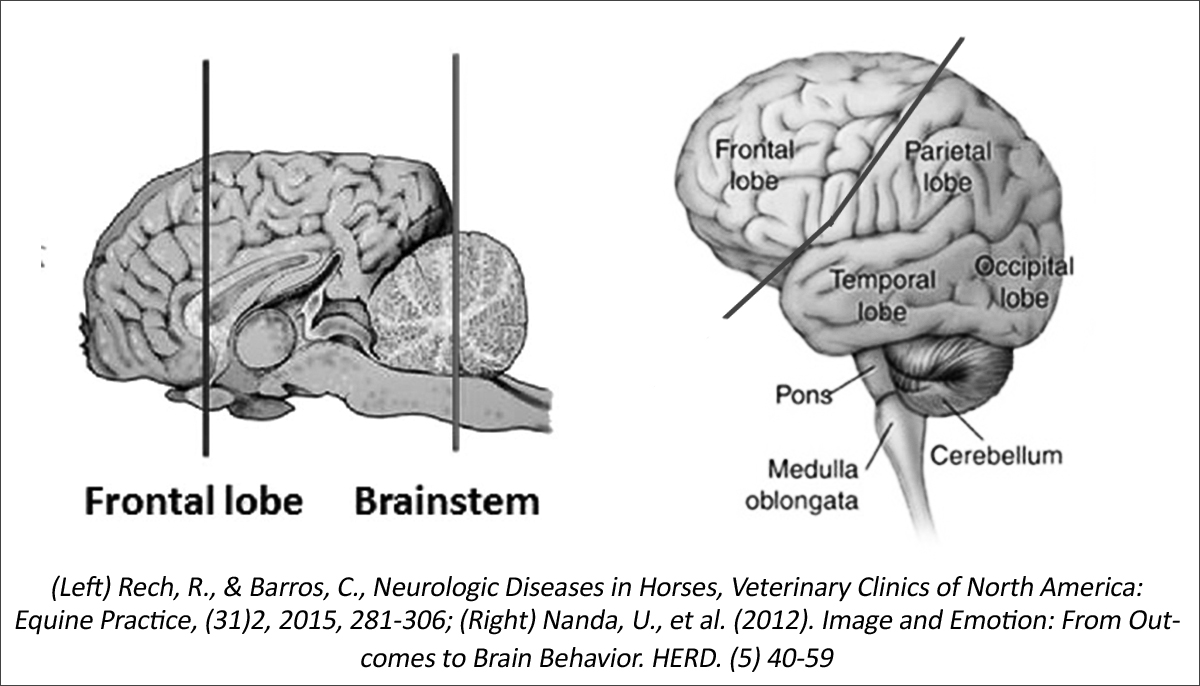

The bigger the frontal lobes, the more capable the species is of ‘goal directed’ behaviors – that is, the ability to analyse information and act accordingly, planning ahead. [2]

Here we hit an issue. The frontal lobes are either relatively small in the horse, or non-existent – and this is a matter of contention. Some published veterinary researchers maintain that they do, as shown below.

However, researcher and author of Horse Brain, Human Brain Janet Jones PhD writes, “Basic anatomy shows that horses have no frontal lobes and no prefrontal cortex. No qualified PhD trained in neuroscience disputes this anatomy.”[3]

Whichever is true, the take home for both is that the horse is more likely to react in the moment. This is not to say that horses lack intelligence, but that they think and respond differently.

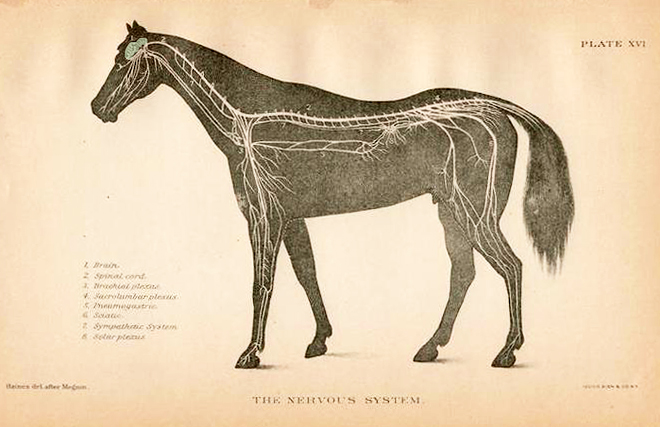

The brain’s fissures are also important. These are the wrinkles and grooves, known as sulci (sunken inwards) and gyri (protrude outwards). They’re standard within species, although the brains of some species have more complex surfaces than others.

Rats, considered to be on the lower end of the intelligence scale of mammals (although rat owners will surely disagree), have smoother brain surfaces than horses. In turn, horses have fewer fissures in their brains than primates.

The area contained within the cranium is the ‘cranial vault’. Its inner surface perfectly matches the outer surface of the brain, as they develop together as the animal grows. If you could look inside this part of the skull, you would see a perfect mould of the fissures.

More recent research also links the organization of neurons (nerve cells) and synapses in the brain to intelligence.

Surely There’s a Difference Between Breeds?

Different breeds of horses certainly have differences in the shapes of their heads.

However, these differences are slight overall. In a study of TBs, STBs and Arabians, the relative proportions of the ‘neurocranium’ – the area above the frontonasal suture, including the cranium – were reasonably similar between breeds.

It was the lower part of the skull, primarily the nasal bones and the maxilla, that varied most and gave the breeds their different looks [4]. The study did not measure the cranium itself.

This suggests that while some breeds may look extremely different – take the Welsh Cob and the TB, for instance – the neurocranium may be nearly square in all, at least when viewed from the front.

And even though some breeds may have proportionately larger heads, all (excluding ponies) will have EQs grouped around the average score of 0.78 mentioned earlier.

Small and wide ponies, incidentally, often have quite large parietal domes (or tuberosities, as they should be known), but the jury is out as to whether this makes them more intelligent… The fact is that we don’t know.

A Little More on Equine Brain Size

There are a few other differences that aren’t documented. Comparing horse skulls, we can see that some have a cranium that is narrower in relation to overall skull width than others. They also vary in shape: some are very full and round, while others are more teardrop shaped.

You can see this when you look at the spaces to either side of the parietal ‘dome’ and temporal bones, where the coronoid processes (tips) of the mandible protrude behind the zygomatic arch.

This may be due to breed or it may be individual. Our own skulls vary from person to person, with some aspects being just how we are, while others may be more developmental.

We can see this in horses too. Dwarf horses can have domed heads, as can horses that have been born prematurely.

This can affect intelligence – researchers have found that in humans, when the brain is smaller due to development delays, the intelligence can be lower. If it is smaller without any developmental delay, it makes no difference at all. [5]

Interestingly, a new study in humans shows that the longer the time Romanian orphans spent in the institutions as babies, the smaller their total brain volume, with these changes being associated with a lower IQ. You can read more about that study here. [6]

Personally, I would love to know more about this, as I’ve been researching the developmental effects of gestational problems in horses, including the effects of premature birth (my PhD thesis lives here). It’s the same old problem though: once a horse is at the stage where we can examine its skull, its early history is usually lost in the mists of time.

Ultimately, as with humans, what is going to make the most difference to us as horse owners is the individual’s learning experiences at different stages of its life. This is also where equine personality comes in, and the methods of training used, but those are different subject areas altogether.

[2] McGreevy, P., Equine Behavior – A Guide for Veterinarians and Equine Scientists, Elsevier, 2012.

[3] Janet Jones – Horse Brains Facebook page

[5] de Bie H. et al. Brain Development, Intelligence and Cognitive Outcome in Children Born Small for Gestational Age. Horm Res Paediatr 2010, (73)6-14.

[6] Mackes, NK. et al., on behalf of the E. Y. A. F. (2020). Early childhood deprivation is associated with alterations in adult brain structure despite subsequent environmental enrichment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.