It’s been a question of mine for a while. Can diagnostic imaging show the presence of transitional vertebrae?

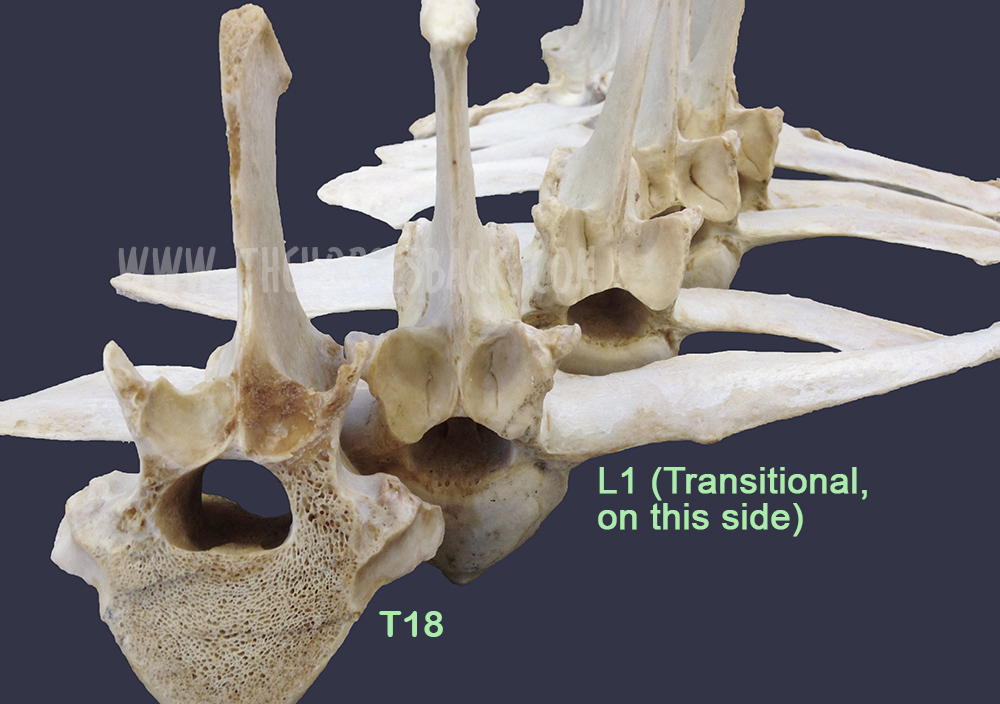

We’re seeing many bone samples from dissections, as shown in my previous article on transitional vertebrae.

But if we’re to help our horses that live with this issue, we need to identify it before they’re dead. (Yes, right?!)

Allow me to introduce a practicing vet and educator who is doing just that.

Imaging for Transitional Vertebrae

Meet Dr Brunna Fonseca, Associate Professor, educator and specialist in equine orthopedics, focusing on the spine and nervous system. She’s based in São Paulo, Brazil.

Meet Dr Brunna Fonseca, Associate Professor, educator and specialist in equine orthopedics, focusing on the spine and nervous system. She’s based in São Paulo, Brazil.

I’ve been following her Instagram for a while, because she posts brilliant videos and photos explaining what she does, and how, and why.

I was delighted to see a recent post on imaging for a transitional vertebra, which included fantastic visuals. Such a great communicator!

Dr Brunna has kindly given me permission to repost her images and descriptions here. So without further ado…

-

All images copyright of Axial Vet

Ultrasonograms

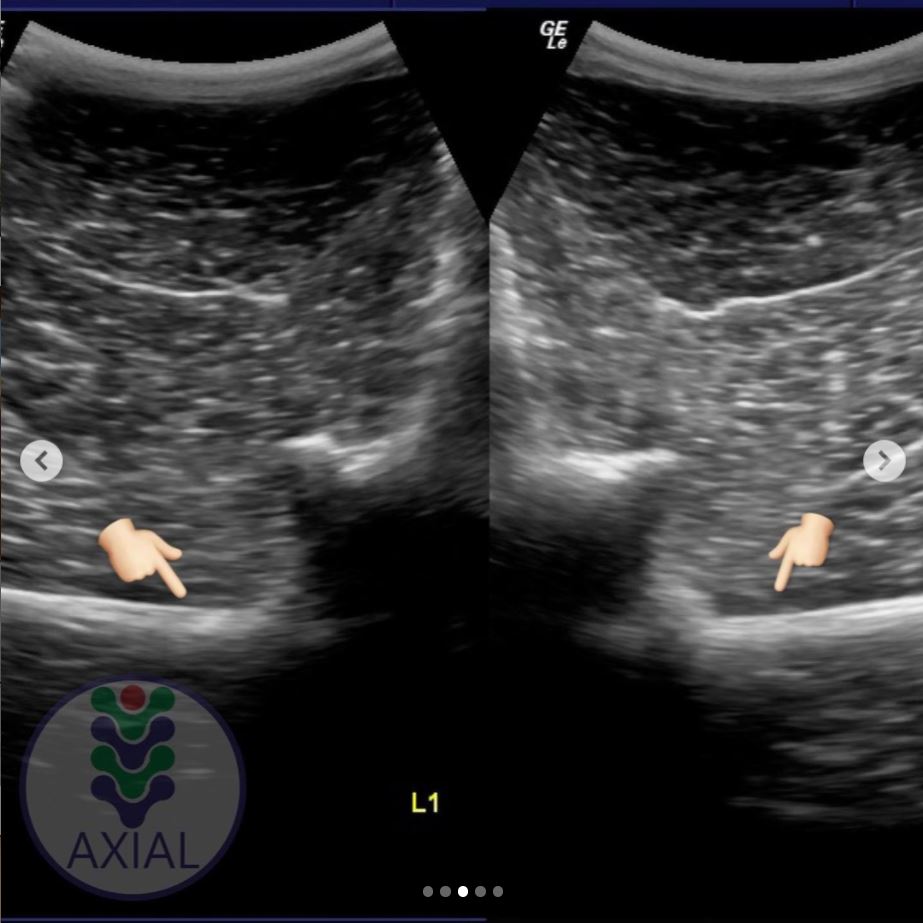

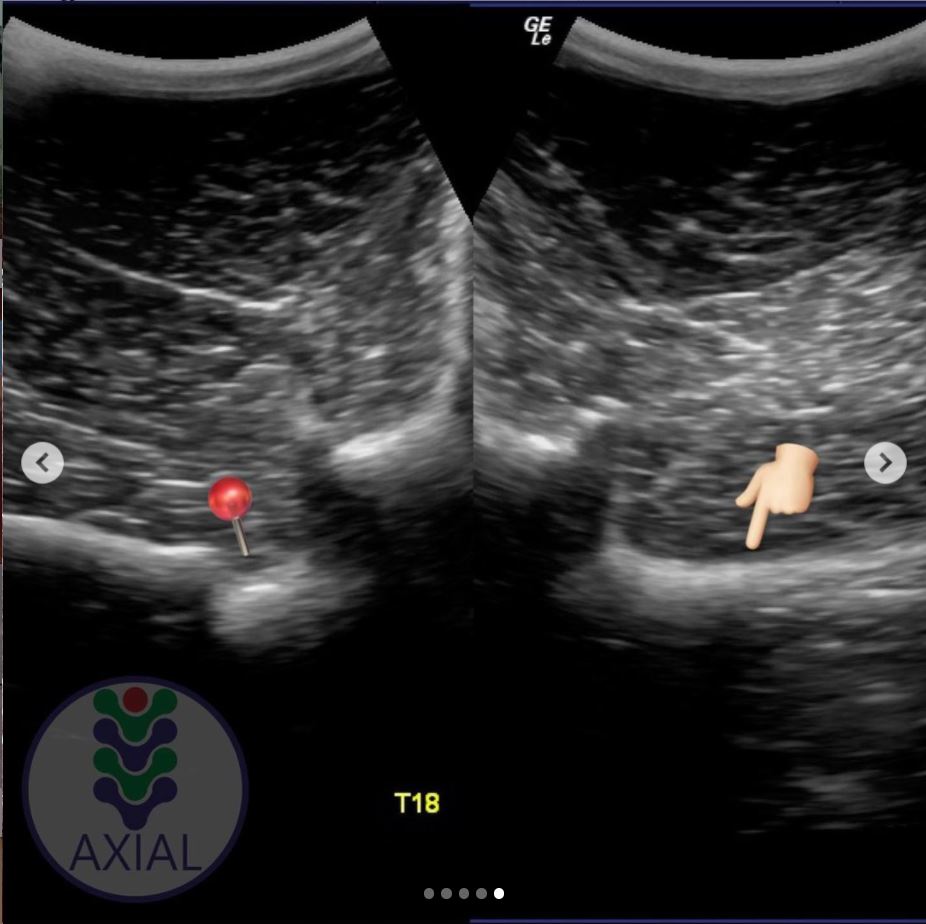

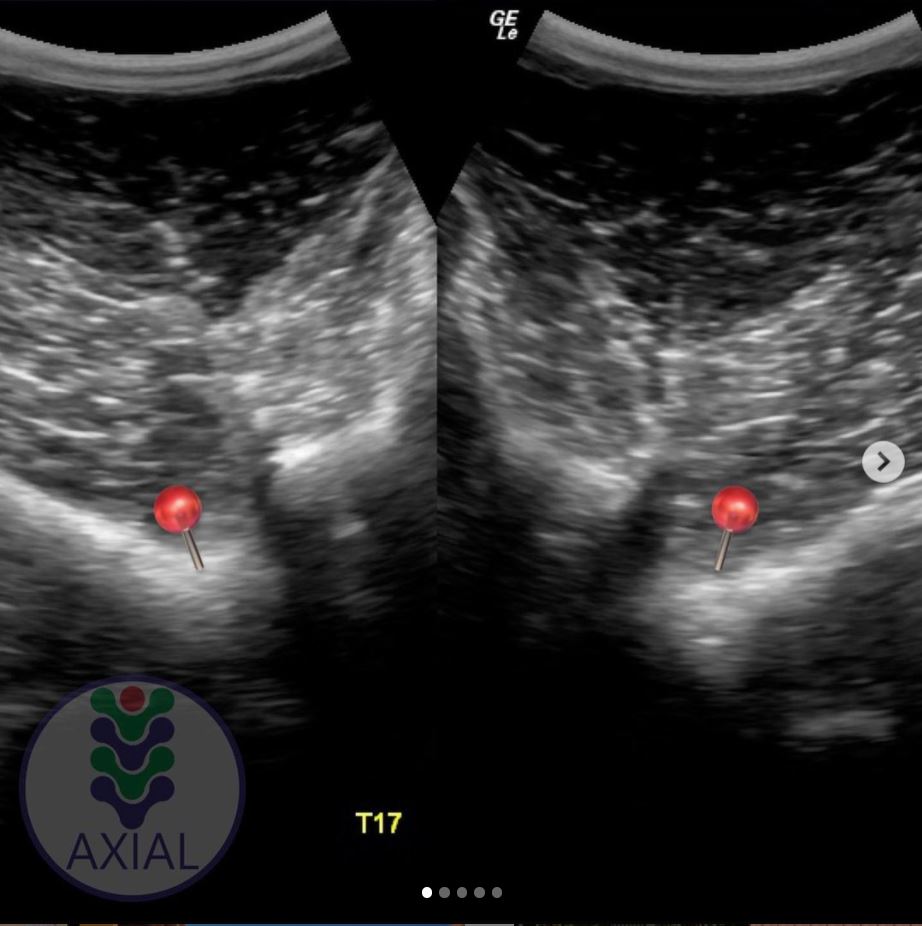

The following ultronographic images are each a composite of two images, one showing the left side and the other the right.

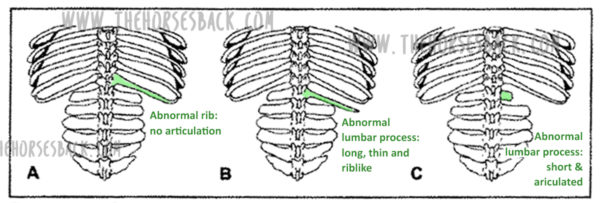

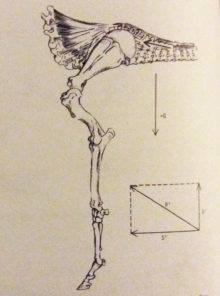

This textbook illustration helps to show the angle the image is taken at. This angle is usually used for imaging the articular facets of the vertebrae.

Additionally, the image at the top of this article shows a transitional vertebra at T18, like the mare being diagnosed by Dr Brunna.

1. Can we recognise transitional vertebrae?

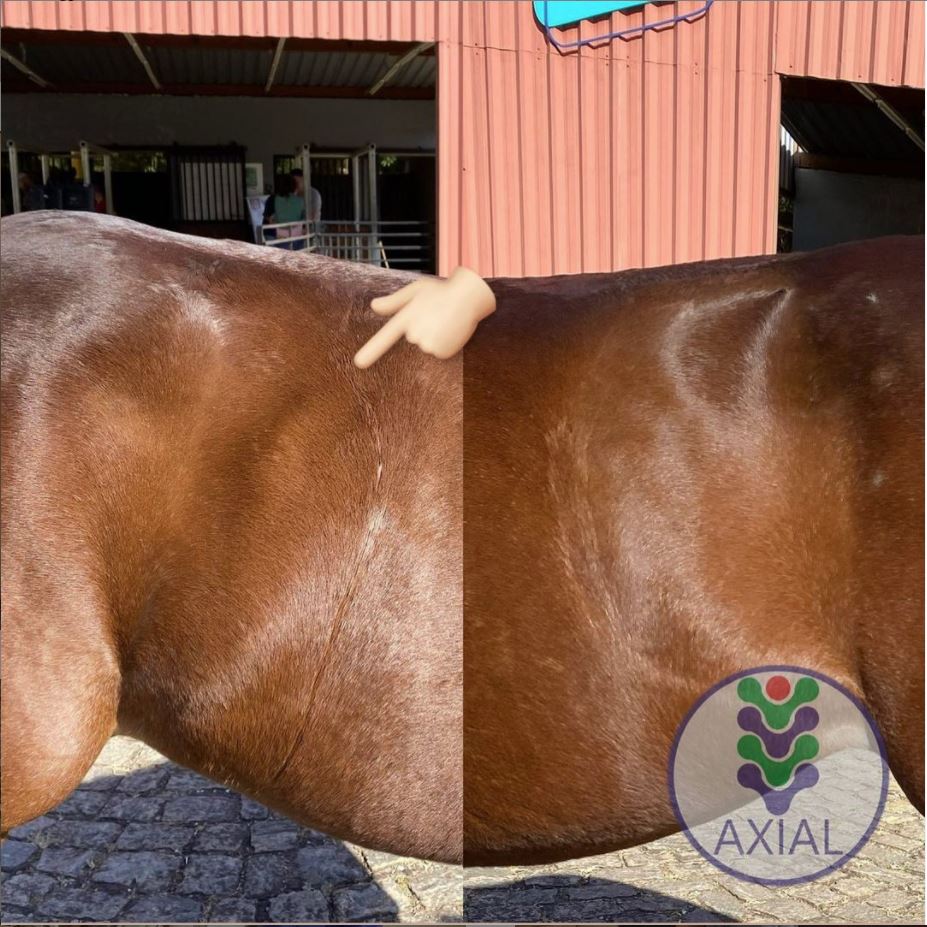

The first image shows two sides of a mare’s body. The hand icon gives us a strong hint of where to look… This appearance is very similar to that of the TB mare in my previous post.

Dr Brunna writes, “This mare has the T18 transitional vertebra, presenting a transverse process similar to the lumbar vertebrae on the right side, which causes the appearance of the horse to have the most visible rib on that side.

The occurrence of transactional vertebrae in the horse is not uncommon, especially in the thoracolumbar transition, which can occur in T18 or L1.”

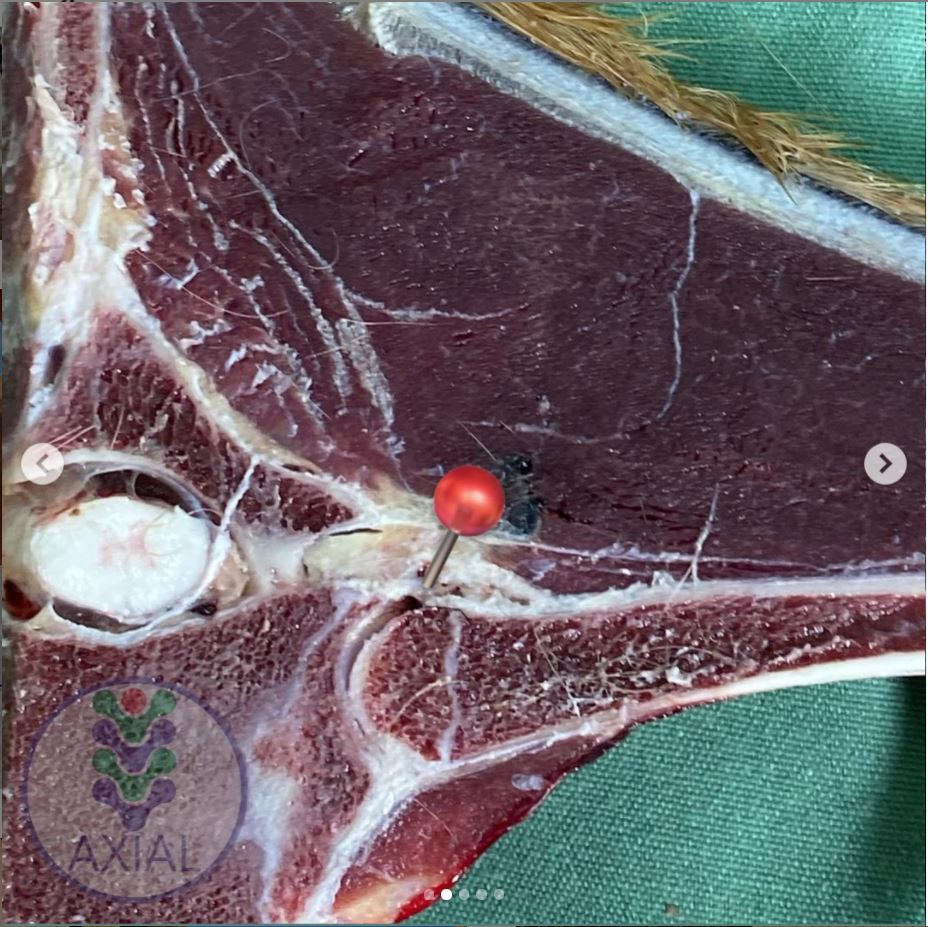

2. Section of a thoracic vertrebra

This image is from a different horse showing a normal rib head and its joint with the vertebra.

Dr Brunna writes, “This is the image of a thoracic vertebra, showing the costotransverse joint.”

3. Image of a normal vertebra

Dr Brunna writes, “This is a T17 ultrasound image, where we can see the image of the normal costotransverse joints.”

This is the bay mare again.

As with the previous cross section, the red pins which show the facet joint between rib head and vertebra.

4. Section of a lumbar vertebra

This is cross section is of a normal lumbar vertebra from a different horse.

As you can see, there is no joint between the transverse process and the vertebral body.

The process is wide and flat, and integral to the vertebra.

5. Image of a lumbar vertebra

5. Image of a lumbar vertebra

Here’s an ultrasound of the first lumbar vertebra (L1) in the bay mare.

As in the above cross section (picture 4), there is no joint between the transverse processes and the vertebral body.

We now have ultrasound images of the normal T17 and normal L1. As we will see, the transitional vertebra mixes elements from both.

6. Imaging transitional vertebrae

6. Imaging transitional vertebrae

“This is an ultrasound image of T18, where we can see the image of the costotransverse joint on the left side (red pin) and image of the transverse process on the right side.”

So here’s the underlying skeletal issue in the bay mare.

The left side is a normal joint, being the same as the T17 thoracic vertebra (picture 3).

The right side is similar to the previous image of the lumbar vertebra (picture 5).

It is not identical, for while the process-like rib is joined to the vertebra, it is not the same shape and does not lie as flat as the lumbar process.

Want to Hear More From Dr Brunna Fonesca?

You can follow her Axial Vet Instagram page to see examples of her equine cases and their assessment, in images and videos.

You can follow her Axial Vet Instagram page to see examples of her equine cases and their assessment, in images and videos.

An increasing number of captions are now translated into English.

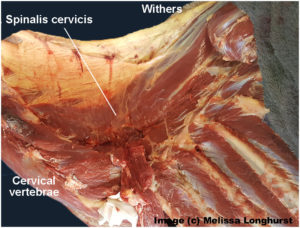

At best, it has no more than a bit part in anatomical illustrations, usually as a small triangular area at the base of the withers. This is also where we can palpate it.

At best, it has no more than a bit part in anatomical illustrations, usually as a small triangular area at the base of the withers. This is also where we can palpate it. Further back along the spine, it lies medially to Longissimus dorsi, and in fact integrates with this larger, better known muscle, attaching to the processes of the lumbar and thoracic vertebrae.

Further back along the spine, it lies medially to Longissimus dorsi, and in fact integrates with this larger, better known muscle, attaching to the processes of the lumbar and thoracic vertebrae. Its integration with other muscles is complex, and its close relationship with Longissimus dorsi partially explains why it doesn’t get much consideration as a muscle in its own right.

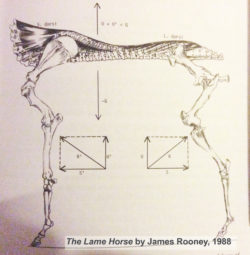

Its integration with other muscles is complex, and its close relationship with Longissimus dorsi partially explains why it doesn’t get much consideration as a muscle in its own right. In his 1980s’ Guide to Lameness videos, Dr. James Rooney, first director of the Gluck Equine Research Center, University of Kentucky, referred to Spinalis as part of the suspension bridge of muscles supporting the spine (Longissimus dorsi achoring from the lumbosacral vertebrae, Spinalis thoracis et dorsalis from the upper thoracics). He also refers to this extensively in The Lame Horse (1988).

In his 1980s’ Guide to Lameness videos, Dr. James Rooney, first director of the Gluck Equine Research Center, University of Kentucky, referred to Spinalis as part of the suspension bridge of muscles supporting the spine (Longissimus dorsi achoring from the lumbosacral vertebrae, Spinalis thoracis et dorsalis from the upper thoracics). He also refers to this extensively in The Lame Horse (1988).

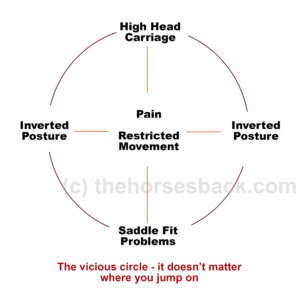

What often happens is this. An overtight saddle fits over the base of the withers like a clothes peg, pinching Trapezius thoracis and Longissimus dorsi. However, it frequently misses Spinalis thoracis where it surfaces, wholly or partially within the gullet space. Often, the muscle is partially affected.

What often happens is this. An overtight saddle fits over the base of the withers like a clothes peg, pinching Trapezius thoracis and Longissimus dorsi. However, it frequently misses Spinalis thoracis where it surfaces, wholly or partially within the gullet space. Often, the muscle is partially affected.

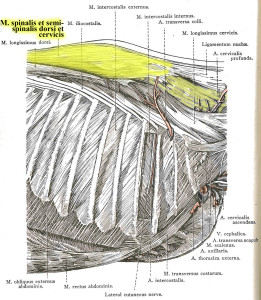

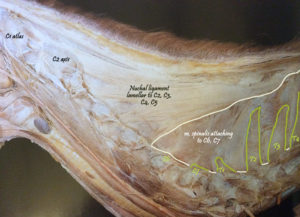

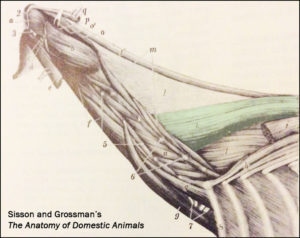

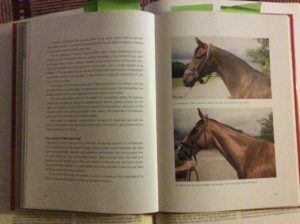

The muscle is tinted green in this image from Sisson and Grossman’s The Anatomy of Domestic Animals, Volume 1, fifth edition 1975. Here, it is labelled Spinalis et semi-spinalis cervicis. This anatomical figure is credited to an earlier text, Ellenberger and Baum, 1908. (added 23 Dec 2016)

The muscle is tinted green in this image from Sisson and Grossman’s The Anatomy of Domestic Animals, Volume 1, fifth edition 1975. Here, it is labelled Spinalis et semi-spinalis cervicis. This anatomical figure is credited to an earlier text, Ellenberger and Baum, 1908. (added 23 Dec 2016)

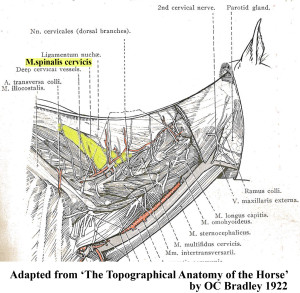

Master Saddler Jochen Schleese refers to Spinalis dorsi and its function in stabilizing the withers in Suffering in Silence, his passionate book about saddle fitting from 2014. “This muscle area is especially prone to significant development – especially with jumpers – because it is continually contracted to accommodate the shock of landing”. The surface area of the muscle is indicated in the anatomical figure, reproduced here. (added 23 Dec 2016)

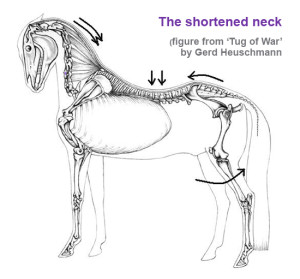

Master Saddler Jochen Schleese refers to Spinalis dorsi and its function in stabilizing the withers in Suffering in Silence, his passionate book about saddle fitting from 2014. “This muscle area is especially prone to significant development – especially with jumpers – because it is continually contracted to accommodate the shock of landing”. The surface area of the muscle is indicated in the anatomical figure, reproduced here. (added 23 Dec 2016) In his seminal text addressing issues of modern dressage training, Tug of War, 2007, Gerd Heuschmann includes Spinalis cervicis in the triangle formed by the rear of the rear of the cervical spine, the withers, and the shoulder blades, “… an extensive connection between the head-neck axis and the truck… it explains how the position and length of the horse’s neck directly affects the biomechanics of the back.” (added 31 Dec 2016)

In his seminal text addressing issues of modern dressage training, Tug of War, 2007, Gerd Heuschmann includes Spinalis cervicis in the triangle formed by the rear of the rear of the cervical spine, the withers, and the shoulder blades, “… an extensive connection between the head-neck axis and the truck… it explains how the position and length of the horse’s neck directly affects the biomechanics of the back.” (added 31 Dec 2016)

![Nuchal ligament, 5yo TB [click to enlarge]](https://thehorsesback.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Nuchal-Ligament-Tb-5yr.jpg)