Did laminitis, trauma, nutrition, disease, or something else cause these hind hoof rings?

Recently I came across hoof rehab specialist Daisy Bicking’s view as to an additional cause of these rings. What she said on the subject made me sit up a little – OK, a lot.

Daisy is an internationally renowned expert of nearly 20 years’ professional standing (see: School of Integrative Hoofcare) who has radiographed hundreds if not thousands of hooves during that time.

Daisy took the picture at the top of this post, and here are her views on what’s happening.

Hind hoof rings and ataxia

Daisy explains that she has seen a correlation between these deep rings and ataxia.

‘Horses that get these repeated deep rings on their back feet (usually not found on the front feet) have been diagnosed or suspected of having some kind of neurological problem which impacts the stability of the hind end.

‘The waves in the hoof come from the horse’s efforts to stabilize.

‘I work on a large population of horses who have neurological issues. Not every one of them gets these rings.

‘But a high level of correlation leads me to believe that if I see these rings (hind feet, deep, symmetrical, predominantly in the quarters) I suspect some instability in the hind end of the horse.

‘It’s not very common but there’s definitely a correlation with neurological problems when I see them like this.

‘When a horse is ataxic, they spend a lot of their time trying to stabilize. This creates a sway pattern that some horses with neurological issues experience more than others.

‘I see it the most with horses who have permanent ataxia from things like EPM, arthritis in the vertebrae, etc.’

Yowzers.

The fact that I’m writing about this here is because within a month, I was able to apply her thinking to two cases I worked with.

Here’s the first.

The horse who convinced me

Take a look at this Australian Stock Horse mare with a very obvious stability issue. At this point, she was recovering from a pelvic fracture.

I can honestly say that in 18 years, I’ve never worked with a horse less stable.

The photo with the hind legs on an angle? Some days, that was the only way she could stand (and yes, she’s lucky to still be here).

In the hoof pictures, the deep and evenly spaced rings are evident.

We might say that these are only caused by trauma, but that doesn’t account for the repeated incidence of these rings, or their spacing.

And just look how there’s a difference in the nature of the front and hind hoof rings. The front hoof rings are raised, but the hind hoof rings are also sunken.

What’s more, trauma and ataxia can go hand-in-hand when associated with the same event.

What’s up with these hind hoof rings?

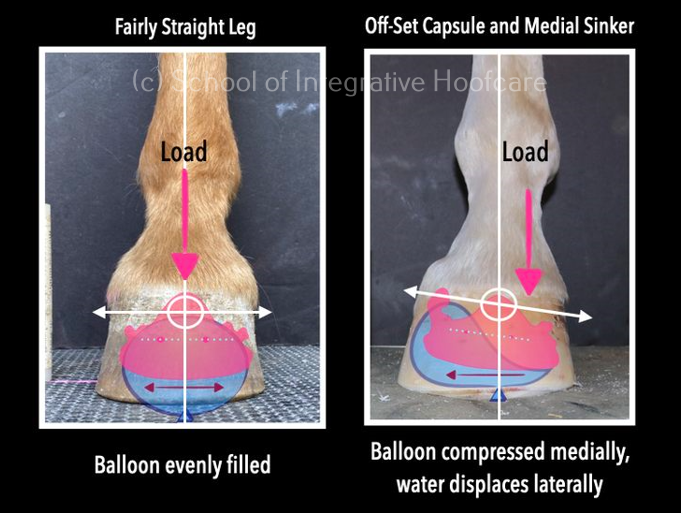

Daisy explains that the mechanism comes down to changes in blood perfusion in the hoof.

‘Think of the blood flow in the foot like a water balloon. How the foot is loaded greatly impacts where/how the fluid perfuses the blood vessels. The more blood flow, the faster growth.

‘The sway creates a variation of load and subsequently blood perfusion that is unique to horses with certain ataxic conditions. Therefore we see these unique rings crop up in the feet.

‘I think where we see them and how long they stay depends on the degree of ataxia the horse is experiencing. If the neurological issues stick around, then they may have them forever.

‘If they are predominantly unsteady on the hind end then we see the rings on the back feet. Versus having ataxia on the front and hind ends, [when] you may see it on all four feet.’

Assessing a horse with hind hoof rings

Now, here’s an interesting 5-yo OTTB mare.

I’d previously seen this mare dropping out and running / trotting behind during canter, which had made me curious.

Upon meeting her, my eyes were soon drawn to her hind hooves.

Upon meeting her, my eyes were soon drawn to her hind hooves.

Clearly they’ve plenty of problems, as is the case with many horses off the track. I was anticipating low heels and potential issues with pedal angles. But what caught my attention more was the series of rings.

These aren’t as pronounced as those in the above photos, and they’re in a tight band, but they’re certainly interesting. And they made me think about hind end sway.

In fact, they encouraged me to do a simple test: placing her right hind foot across the midline to rest in front of the other.

Well, that revealed something: this girl didn’t replace her right foot for a long time. And she didn’t do that twice, because I repeated the test.

The horse not noticing foot placement in this way is a sign of possible neurological issues. They will usually replace it immediately.

Next, I lifted the right hind leg up and found it to be super stiff and heavy. It look real effort to lift it. Same with the left.

That’s not at all what I’d expect with a healthy young TB. And in case you’re wondering, her lumbosacral area was definitely weak – yet with sacroiliac pain, I’d expect a hind foot to be quickly lifted high, either medially or with a lateral ‘be careful’ flick. She did neither of those things.

What about the location of those rings?

By their position and general speed of hoof growth, the rings could be backdated to an event about 6 months ago.

This doesn’t change an assessment of instability – quite the opposite, as a fall might have caused ataxia OR it might have resulted from existing ataxia.

And looking closely, it does appear that the some parallel spaced rings are emerging (red arrows). Could this be a developing issue?

And could she be ataxic in front too?

More circumstantial evidence: the mare was unable to place her foot on a ramp while walking freely forwards.

The final images shows what kept happening when she tried placing the foot, without success, before stepping back.

This she did several times, getting it wrong each time, despite having loaded on this vehicle before. You’d expect her to quickly figure it out after learning where the slope was.

It appears to be a proprioceptive issue, as her timing and spatial awareness are somewhat off.

If Daisy is right here, we can speculate that the hoof rings are reflecting ataxia that currently affects hindlimbs, but is also affecting the forelimbs to a degree. And there’s more than one known pathology that could be causing this.

Where to next?

I’m finding this exploration interesting and will keep making my own observations. I really believe that it’s worth checking in with a new idea by looking at how it plays out with your own cases. Even then, it’s important to test the idea and consider it as a possibility rather than gospel truth.

That said, one thing I’ve learned through research is that fresh scientific findings frequently begin not only with published literature, but also with strong anecdotal evidence gathered by experienced observers over a period of time. Sometimes, solely so.

As these professionals then research the literature, further context is provided by previous studies – if they exist, that is.

I truly hope that the data Daisy has generated and the insight she has developed through hoof rehabilitation does find its way into the equine scientific literature.

Horses can only benefit from new findings that bring greater understanding to hoof-body relationships in the domestic horse.

More about Daisy

Daisy Bicking DEP, APF-I, CFGP, CLS, CE/CI is passionate about helping horses and the people who care for them.

Through Daisy Haven Farm, she supports the equine community by providing whole horse hoof care and rehabilitation services, designed to promote physical, mental and emotional well being.

She also spearheads the School of Integrative Hoofcare which provides education about the hoof and horse via in-person workshops, one-on-one mentorships, and virtual educational courses.