It’s a problem of a pressing nature. In some horses with upright, contracted and sheared heels, I’ve seen first hand how the lateral cartilage can painfully impinge the back of the pastern. Sometimes this leads to a gait anomaly and in some horses, this has looked an awful lot like lameness.

Full disclosure here: I’m a bodyworker, not a hoof care practitioner. But everything I’m going to mention I gleaned from the horses’ reactions to focused palpation. My take is that I’m working above the hairline, so I’m OK to offer my observations…

Full disclosure here: I’m a bodyworker, not a hoof care practitioner. But everything I’m going to mention I gleaned from the horses’ reactions to focused palpation. My take is that I’m working above the hairline, so I’m OK to offer my observations…

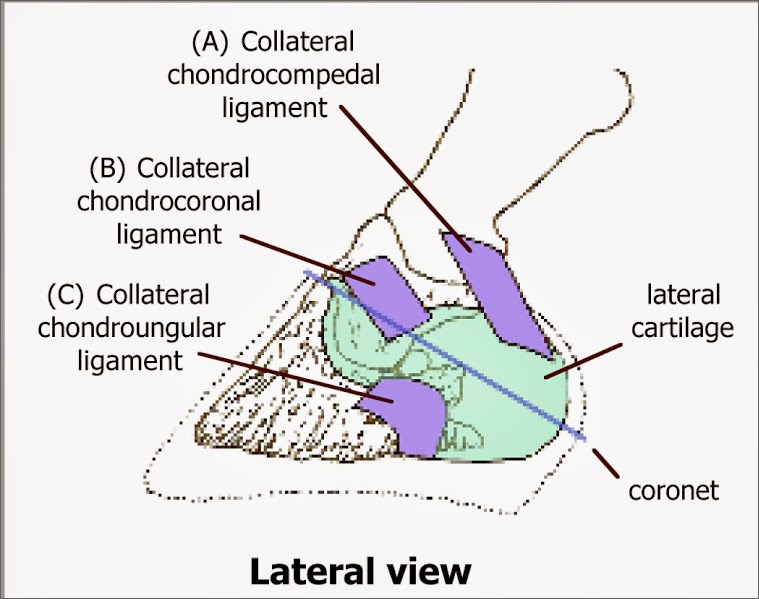

But first, a point about language. Different countries favor different anatomical terms and depending on your part of the world, the lateral cartilages may variously be called collateral, ungual or ungular cartilages.

Anatomy’s just like that. In this article, I’ll be sticking with lateral.

My thanks to go Paige Poss, Anatomy of the Equine, who wrote this interesting article in The Horse about the heel structures of the foot, and to Megan Matters of Hoofmatters for their help discussing this post with me.

Ed. OK, it seems I need to say this: I am not saying this is the only source of caudal hoof pain. There are obviously many and hoofcare is a huge topic. What I’m saying is that there’s a specific location for pain that bodyworkers, and anyone for that matter, can palpate for, and it’s often very useful to know about it, so you can start to do something about it.

What and where are the lateral cartilages?

The lateral cartilages of the hoof are interesting in that they are attached to the pedal bone (third phalanx), extending up and above the hoof capsule.

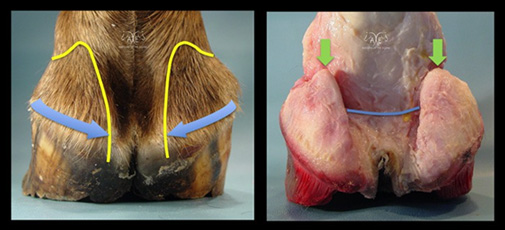

Here’s an image showing where they can be easily palpated in the living horse. The red line shows the palpable edges, where they rise above the heel bulbs at the back of the foot. Each cartilage then extends about two thirds of the way forwards on either side, still above the coronary band.

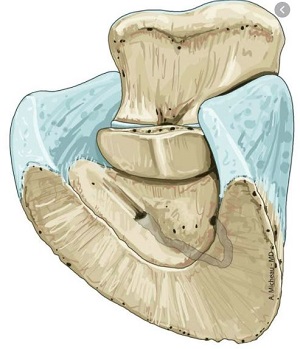

Now, here’s a wonderful illustration showing where they’re located in relation the skeletal structures. This shows the short pastern bone, the navicular and the pedal bone.

What’s their function? This I’ll leave to the experts. Here’s a quote from a paper by Sue Dyson and Annamaria Nagy, who in turn reference Prof Robert Bowker in describing how many other structures connect to the cartilages:

“The cartilages of the foot are connected to surrounding structures, such as the digital cushion, proximal, middle and distal phalanges and navicular bone by small ligaments… The cartilages of the foot are thought to reduce concussion to structures within the foot (Bowker et al. 1998) and to assist blood flow by compression of the venous plexuses of the foot during loading”. [1]

How high heels can affect the lateral cartilages

Now, I’m coming at this from the direction of one particular issue. To sum it up: when there’s a high heel or mediolateral imbalance in the lower limb and hoof, the lateral cartilage can be pressed against the short pastern bone.

Sometimes, this can be painful. When we press the cartilage, the horse pulls the foot away.

Let’s take a quick look at how the hoof balance and in particular high heels can create these pressure points.

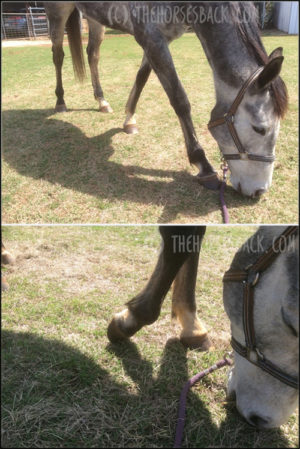

In this next photo, the foot on the right is clearly higher and the heels are more contracted.

As you can see, this has an effect on the position of the lateral cartilages, bringing them higher and closer into the pastern.

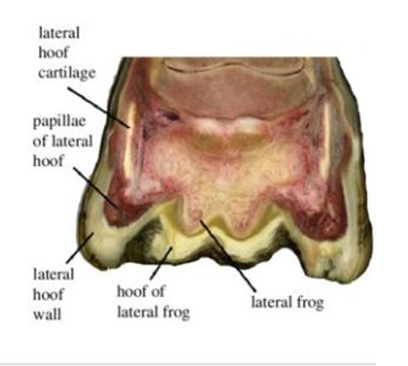

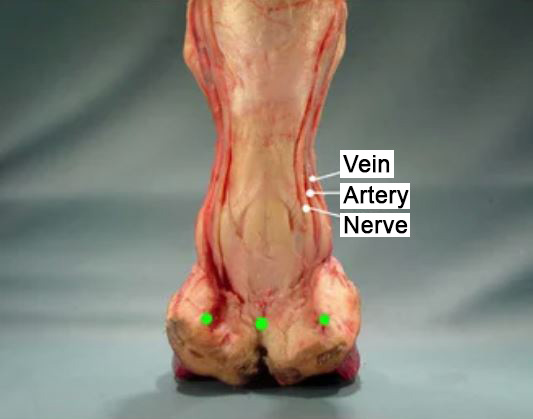

Now for a dissection image from Paige M Poss showing these structures in a flat hoof, both before and after the skin and hoof capsule are removed.

The cartilages are well away from the bone, because with an undeveloped digital cushion, the heels in this horse had collapsed. As you can see, the cartilages are wide of the pastern here.

Next, a companion image showing the same structures in a more contracted hoof. The heels are upright and the cartilages are pushed inwards.

There’s also a mediolateral imbalance, with one side being higher and more contracted than the other. As a result, the left cartilage is flatter and compressed inwards towards the bone.

Now here’s an image of the transverse section of a hoof (ie. sliced vertically, left to right) from a ppaer by Nikos Solounias.

Here we can see that on the right side, which is the more compressed side, the space between the cartilages – the thick, white upright structures – and the short pastern bone is narrower.

Where this leads us now is towards sheared heels, when there’s a dramatic difference in heel height. When this happens, not only is the heel higher, but the mediolateral imbalance causes narrowing of the pastern joints on that side as well. This tilt increases compression further, while the low side heel may become crushed.

Finally, here’s an image of badly sheared heels in a racehorse by Scott E Morrison, DVM, of Rood and Riddle Equine Hospital. I’ve taken the liberty of rotating it too, so you can see how high that heel is. It’s not a pretty foot.

That’s plenty of description for now. What we need to think about next is what the horse might be feeling.

What are the signs of pain?

In bodywork sessions when addressing the forelimb, I often start at the foot and work up. I rotate the pasterns and mobilise the joints, but before that, I check the lateral cartilages.

As part of this, I raise the foot and press inwards on the peaks of the cartilages, shown as red spots on this image. At this point, some horses will attempt to pull the foot sharply away. That’s what happened with the right side of the foot shown in this image.

I also gently lift the cartilages a couple of millimeters outwards, with my thumbs placed on the palpable edge, shown with the white arrows. Again, some horses will snatch the foot away in response to this. They usually do this in relation to one cartilage only.

It’s a clear sign of pain, particularly if the horse does it a second time when either of these actions is repeated.

What’s actually causing this pain?

There are a few candidates for what’s actually hurting when the upper edge of the cartilage is pressed towards the pastern.

1. Could it be the start of sidebone, which is the condition when the cartilage begins to ossify? There is some limited evidence that sidebone can be painful, linked primarily to fracturing ossified cartilage or pedal bone. So generally, this is unlikely.

2. Pain could also be caused by an injury to one of the many ligaments attached to the cartilage. It’s possible that tweaking the lateral cartilages outwards might cause a pain response here.

3. There’s that palmar digital artery. If the cartilage is pressing against it, then there could be restriction. Might that be uncomfortable or painful?

4. The region between the lateral cartilage and the pastern bone is also filled with stabilizing ligament. Constant pressure could potentially create lesions here.

5. There might also be an indirect pressure on the deep digital flexor tendon that runs centrally down the back of the pastern. Might be, but seems less likely in the absence of an obvious lameness suggesting a lesion.

The fact is that we could be looking at one or a combination of these factors when pain is present when we press the upper edge of the cartilage.

This pressure might be creating pressure on the nerve or artery or both.

With potential causes that are so small and focused, it’s impossible to tell without veterinary imaging and diagnosis. As so often, we answer a question with more questions.

Thermal imaging

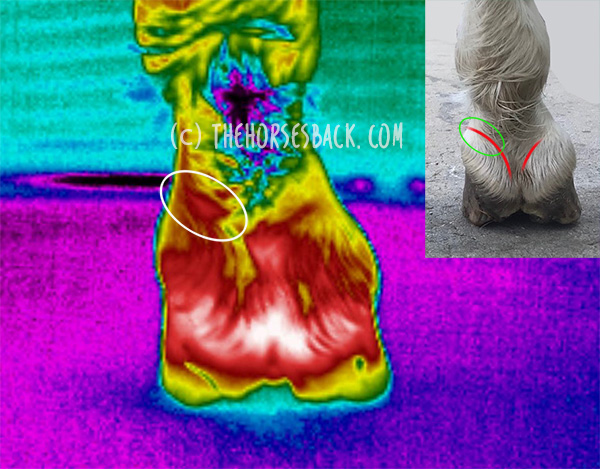

I recently took this infrared thermal image of the rear of an upright foot.

Now, there’s a lot to explain about thermal images, for there are many variables that affect the results. But I’m keeping this simple for now by showing just the one photo.

This hoof was already showing a higher thermal signature than the lower hoof (not shown – like I said, keeping this simple).

Note that it’s normal for the concave area at the back of the pastern and hoof to be warmer (although it shouldn’t be warm so far down the hoof).

What I’m wanting to show you is the spot marked with an oval. We have an obviously warmer spot just above the lateral cartilage here.

Granted, this is in an area where there’s vascular activity, as the palmar digital artery and vein are nearby.

However, it’s not just that, for the thermal reading is 2 °C (35.6 °F) warmer on this upright hoof than in the same spot on the lower hoof. And yes, I compared them within the same image.

This doesn’t provide evidence of the reason for the increased heat. Inflammation within the hoof capsule is always a possibility, although I’d expect both veins to be affected.

I happen to know that this horse didn’t have an abscess.

However, the horse palpated positive for pain over the left lateral cartilage, which was tight against the pastern.

Given that his reluctance to load the hoof disappeared with the tiniest of micro-trims on that wall, it appears that pressure was a likely cause.

So what do we do?

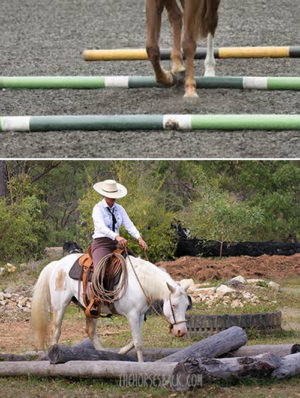

All we can know is that hoofcare needs to be optimized, to ease pressure in every respect.

While I’m unable to say exactly what hurts, the effect of additional caudal hoof pain is clear.

If compression in this area is painful, descending hills and turning on that hoof is also going to be problematic at times. It could be behind some of the hesitations that can’t be otherwise explained.

Meanwhile, any trim that fails to adequately address heel height, sheared heels or mediolateral imbalance is going to potentially contribute to this existing painful situation.

Why? Because it feeds into the ‘unloading spiral’.

When pain or discomfort is present, the horse is less inclined to load that foot, particularly at rest. The less loaded foot will then tend towards remaining upright, or may even become more upright, leading to an intensification of the problem.

As I’ve said, I’m not a hoofcare expert. But manifestations like this help me to advise clients when they should be talking to their farriery expert, and if that doesn’t work, maybe switching to another one.

References

-

-

Dyson, S. and A. Nagy, Injuries associated with the cartilages of the foot, Equine Veterinary Education, 2011, 23, 581-593. doi.10.1111/J.2042-3292.2011.00260

-

Solounias Nikos et al. 2018. The evolution and anatomy of the horse manus with an emphasis on digit reduction R. Soc. open sci. 5171782171782

-

Scott E Morrison, DVM, AAEP proceedings, vol. 59, 2013

-

Onar V et al. Byzantine Horse Skeletons of Theodosius Harbour: 1.Paleopathology, Revue de Médecine Vétérinaire, 2012, 163(3):139-146

-

Lancaster LS, Bowker RM. Acupuncture Points of the Horse’s Distal Thoracic Limb: A Neuroanatomic Approach to the Transposition of Traditional Points. Animals (Basel). 2012 Sep 17;2(3):455-71. doi: 10.3390/ani2030455

-

Tension also builds because the horse is trying – and failing – to balance their weight centrally.

Tension also builds because the horse is trying – and failing – to balance their weight centrally.