In this guest post, Tanja Kraus introduces variable feeding positions, which bring musculoskeletal benefits while also enriching your horse’s day.

As an equine educator from the East Coast of Australia, Tanja’s passion is using kind horsemanship philosophies and connection to develop a partnership horse with the rider.

This extract comes from her latest book, Lessons from Horses: Movement, whch provides insight into why and how our horses should be moving each day, with exercises to contribute to their physical health, mental wellbeing, and longevity.

She writes about variable feeding positions with the support of Dr Sharon May-Davis, who developed this combined feeding approach.

You can find Tanja’s books here.

All text is copyright of the author Tanja Kraus. No reproduction without permission.

The Day I Heard About Variable Feeding Positions and Horse Posture

I first heard about variable feeding positions when attending an Equine Symposium where Dr. Sharon May-Davis was presenting.

Sharon presented on variable feeding positions, and showed many examples of the benefits of variable feeding she had seen, both in wild horses and in domestic horses managed in this way.

This included reduced asymmetry in the body, improved teeth and hooves, a more complete and balanced recovery from injury, and improved performance across multiple disciplines.

Comparing wild herds to domestic horses, she discovered that domestic horses with restricted lifestyles suffer with issues not only in the musculoskeletal system, but also uneven teeth wear. Jaw alignment and foot growth due to the limited postures.

Natural Feeding Behaviors in Horses

As Dr May-Davis was talking, I was imagining my own horses and what I had seen them doing naturally in their paddock, and she was, of course, right.

My own horses who run in a herd of around 10 (give or take) in a paddock of varying terrain of about 40 acres adopt ‘variable feeding positions’ regularly and quite naturally.

And when I say regularly, I mean daily, through all the seasons.

So, they are not driven by lack of resources, which many people will argue ‘horses only eat out of trees when they have no choice’ – this is 100% incorrect.

My horses will happily roam their paddock and graze and browse and everything in between every day.

We’re fortunate that our paddock contains a wonderful variation of pasture, different types of grasses, trees, and weeds that our horses can pick and choose from.

They are regularly seen choosing to eat ‘above the knee’, which is the measurement used to define browsing.

This can involve something as simple as eating the top of long grass around knee height, to completely outstretching their head and neck until their teeth are facing the sky to pull leaves from trees.

When you observe horses doing this, and pay attention to their bodies as they do it, you can see just how significant the range of motion is.

Naysayers are often heard grumbling that horses ‘shouldn’t hollow their backs’ and that ‘high feeding is bad’ for this reason.

However, if you observe other animal species such as dogs and cats, they can all be seen stretching their spines by rounding and then hollowing.

And where would our own Yoga classes be without the classic ‘cat / cow’ pose? Range of motion is healthy, natural and necessary.

Our domestic horses are often denied any type of variable feeding as we feed hay and hard feeds on the ground, and many horses are kept in paddocks that have limited access to appealing trees, shrubs, and long grass to facilitate variable feeding.

So how can we help?

Offer Your Horses Variable Feeding Positions

Provide opportunity for variable feeding, with the following examples:

- High hay fixed

- High hay swinging

- High feeder on rail

- High feeder with ramp

If hay has to go on the ground, you can make use of the natural lie of the land.

- Feed on slope uphill / downhill

- Hay scattered around to encourage movement

- Multiple haynets and feeders to encourage movement

The Benefits of Variable Feeding Positions

Basically, we can try any variation from the usual static grazing position.

Feeding in variable positions can also be a useful ‘passive physio’ technique. They may find it harder at first, but it gets easier as their bodies become more supple and mobile.

It follows that horses being rehabbed from injury or restriction can be fed to encourage beneficial postures that activate or stretch particular muscles or body areas.

It’s important to note here that I have had some equine dentists express concern as they have seen terrible damage to horses’ teeth (namely racehorses) who are fed only in high feeders.

But, those horses are stabled and fed only in up positions, and therefore the grazing position is not a part of their daily routine. A recent study suggests there is no negative dental effect in horses using haynets for a period of one year [1].

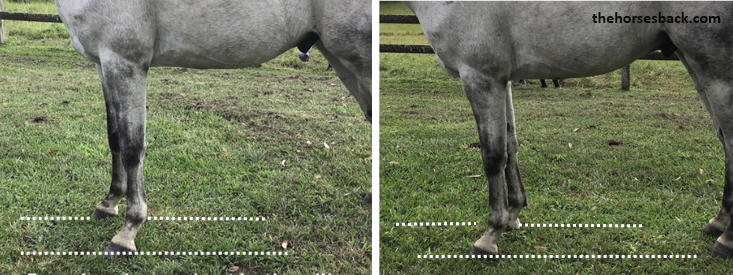

Below, these horses are fully mobilising their necks while eating from a shared large small-hole haynet – and from the ground. Note the near squared position of the grey mare, who suffered a fractured pelvis as a yearling.

We can also reverse engineer this – if your horse has an asymmetry, or difficulty working in one direction, is the way you position their feed having a negative effect?

Horses, when given the freedom to choose, graze approximately 80% of the time, and browse 20% of the time, and this balance should be sought when providing variable feeding positions for their benefit.

I have adopted variable feeding positions for my own horses, student horses, and for horses when they come in for training.

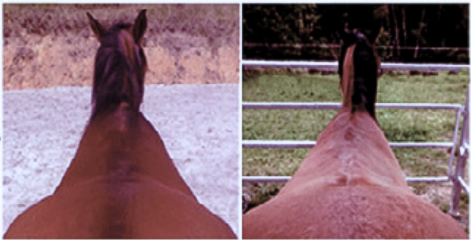

I’ve taken photos and filmed their start of variable feeding, and as they progress, and I have noticed a significant improvement in their posture while eating, along with their resting and grazing stances.

Depending on what you are trying to achieve there are many options, and the best part is the horse is doing their own physio in a gentle way.

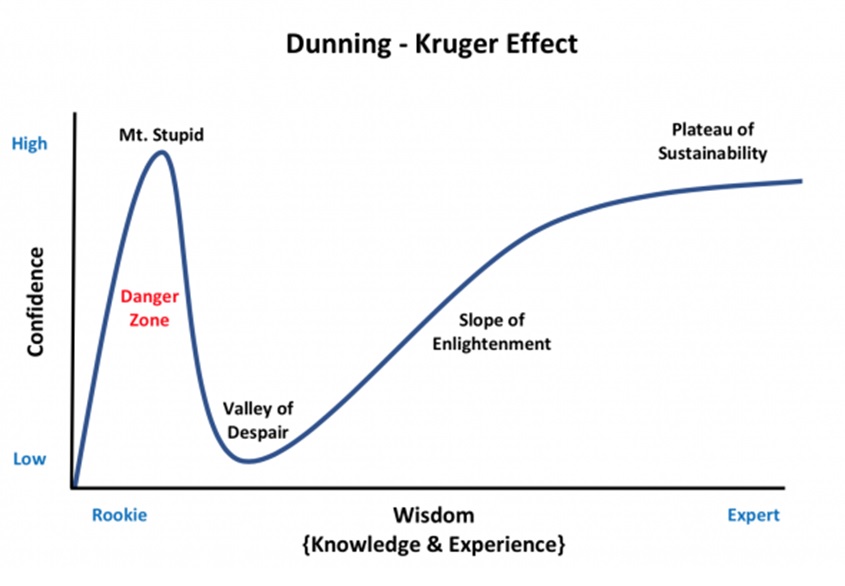

There’s a basic premise of saddle fitting that hasn’t occurred to a lot of people. It can’t have done, not if the tack they’re riding in is anything to go by.

There’s a basic premise of saddle fitting that hasn’t occurred to a lot of people. It can’t have done, not if the tack they’re riding in is anything to go by. The reason for this statement is simply to highlight the fact that inserting a relatively static piece of equipment between two living organisms in motion is, at best, always going to be fraught with complexity.

The reason for this statement is simply to highlight the fact that inserting a relatively static piece of equipment between two living organisms in motion is, at best, always going to be fraught with complexity.