Here are abstracts, downloads and links for my research into the ongoing effects or premature or dysmature birth in horses.

Here are abstracts, downloads and links for my research into the ongoing effects or premature or dysmature birth in horses.

These are the publicly available details of my thesis (full download) and published, peer-reviewed journal articles. The articles aren’t open access, but if you really want to read something, please contact me.

As always, huge thanks are due to the breeder owners who so very kindly allowed me to study their horses, and who provided such valuable images. Together, you’ve helped me to learn a lot and reach initial findings that I now hope to pass on.

Beyond the Miracle Foal: A Study into the Persistent Effects of Gestational Immaturity in Horses

PhD Thesis, University of New England and CSIRO

Abstract

Breeding horses can be a financially and emotionally expensive undertaking, particularly when a foal is born prematurely, or full term but dysmature, showing signs normally associated with prematurity. In humans, a syndrome of gestational immaturity is now emerging, with associated long-term sequelae, including metabolic syndrome, growth abnormalities and behavioural problems.

Breeding horses can be a financially and emotionally expensive undertaking, particularly when a foal is born prematurely, or full term but dysmature, showing signs normally associated with prematurity. In humans, a syndrome of gestational immaturity is now emerging, with associated long-term sequelae, including metabolic syndrome, growth abnormalities and behavioural problems.

If a similar syndrome exists in the equine and can be characterised, opportunities for early identification of at-risk individuals emerge, and early intervention strategies can be developed. This thesis explores the persistent effects of gestational immaturity manifest as adrenocortical, orthopaedic and behavioural adaptation in the horse.

Basal diurnal cortisol levels do not differ from healthy, term controls, but when subjected to a low dose ACTH challenge, gestationally immature horses presented a depressed or elevated salivary cortisol response, suggesting bilateral adaptation of the adrenocortical response. This may be reflected in behavioural reactivity, but the outcomes from a startle test were inconclusive.

A survey of horse owners indicated that gestationally immature horses tended to be more aggressive and active than controls, aggression being displayed mostly in families of Arabian horses. Case horses also tended to be more active, intolerant, and untrusting.

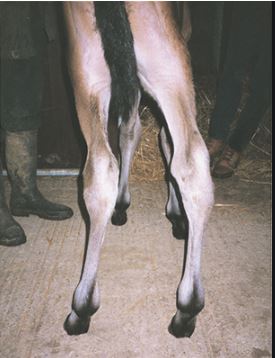

Gestationally immature horses have restricted growth distal to the carpal and tarsal joints, and this results in a more ‘rectangular’ conformation in adulthood compared to controls. They also often present with angular limb deformities that adversely affect lying behaviour and recumbent rest. This, however, can be mitigated using analgesic therapy, suggesting chronic discomfort.

Based on these findings, it is reasonable to postulate that a syndrome of gestational immaturity may persist, both clinically and sub-clinically, in affected adult horses. Further work is required to fully characterise this syndrome and validate the outcomes in larger populations, thereby providing a foundation for interventions applicable in the equine breeding industry.

Here is the downloadable doctoral thesis. This is a 236-page PDF.

Clothier, Jane (author); Brown, Wendy (supervisor); Small, Alison (supervisor); Hinch, Geoff (supervisor)

Equine Gestational Length and Location: Is There More That The Research Could Be Telling Us?

Australian Veterinary Journal

Abstract

Clear definitions of ‘normal’ equine gestation length (GL) are elusive, with GL being subject to a considerable number of internal and external variables that have confounded interpretation and estimation of GL for over 50 years. Consequently, the mean GL of 340 days first established by Rossdale in 1967 for Thoroughbred horses in northern Europe continues to be the benchmark value referenced by veterinarians, breeders and researchers worldwide. Application of a 95% confidence limit to reported GL range values indicates a possible connection between geographic location and GL.

Clear definitions of ‘normal’ equine gestation length (GL) are elusive, with GL being subject to a considerable number of internal and external variables that have confounded interpretation and estimation of GL for over 50 years. Consequently, the mean GL of 340 days first established by Rossdale in 1967 for Thoroughbred horses in northern Europe continues to be the benchmark value referenced by veterinarians, breeders and researchers worldwide. Application of a 95% confidence limit to reported GL range values indicates a possible connection between geographic location and GL.

Improved knowledge of this variable may help in assessing the degree of the neonate’s prematurity and dysmaturity at or soon after birth, and identification of conditions such as incomplete ossification of the carpal and tarsal bones. Associated pathologies such as bone malformation and fracture, angular limb deformity and degenerative joint disease can cause chronic unsoundness, rendering horses unsuitable for athletic purpose and shortening ridden careers.

This review will examine both the factors contributing to GL variation and the published data to determine whether there is potential to refine our understanding of GL by establishing a more accurate and regionally relevant GL range based on a 95% confidence limit. This may benefit both equine industry economics and equine welfare by improving early identification of skeletally immature neonates, so that appropriate intervention may be considered.

The paper can be accessed here.

Clothier, J., Hinch, G., Brown, W. and Small, A. (2017), Equine gestational length and location: is there more that the research could be telling us?. Aust Vet J, 95: 454-461. https://doi.org/10.1111/avj.12653

Using Movement Sensors to Assess Lying Time in Horses With and Without Angular Limb Deformities

Journal of Equine Veterinary Science

Abstract

Chronic musculoskeletal pathologies are common in horses, however, identifying related effects can be challenging. This study tested the hypothesis that movement sensors and analgesics could be used in combination to confirm the presence of restrictive pathologies by assessing lying time. Four horses presenting a range of angular limb deformities (ALDs) and four non-affected controls were used.

Chronic musculoskeletal pathologies are common in horses, however, identifying related effects can be challenging. This study tested the hypothesis that movement sensors and analgesics could be used in combination to confirm the presence of restrictive pathologies by assessing lying time. Four horses presenting a range of angular limb deformities (ALDs) and four non-affected controls were used.

The study comprised two trials at separate paddock locations. Trial A consisted of a 3-day baseline phase and 2 × 3-day treatment phases, during which two analgesics were administered to two ALD horses and two controls in a standard crossover design. Trial B replicated trial A, except that as no difference between analgesics had been evident in trial A, only one analgesic was tested. Movement sensors were used to measure the horses’ lying time and lying bouts.

In trial A, ALD horses’ basal mean lying time was significantly less than controls (means ± SD for ALD horses 213 ± 1.4 minutes and for controls 408 ± 46.7 minutes, P = .007); with analgesic administration, the difference became nonsignificant. In trial B, ALD horses’ basal mean lying time was also significantly less than controls (ALD horses 179 ± 110.3 minutes; controls 422.5 ± 40.3 minutes, P < .001), again becoming nonsignificant with analgesic administration. Given the increases in ALD horses’ lying time with analgesic administration, it is possible that their shorter basal lying time is associated with musculoskeletal discomfort. Despite the small sample size, movement sensors effectively measured this behavior change, indicating that they could be a useful tool to indirectly assess the impact of chronic musculoskeletal pathologies in horses.

The paper can be accessed here.

Clothier J, Small A, Hinch G, Barwick J, Brown WY. Using Movement Sensors to Assess Lying Time in Horses With and Without Angular Limb Deformities. J Equine Vet Sci. 2019; 75:5559. doi: 10.1016/j.jevs.2019.01.011

Prematurity and Dysmaturity Are Associated With Reduced Height and Shorter Distal Limb Length in Horses

Journal of Equine Veterinary Science

Abstract

The long-term effects of gestational immaturity in the premature (defined as < 320 days gestation) and dysmature (normal term but showing some signs of prematurity) foal have not been thoroughly investigated. Studies have reported that a high percentage of gestationally immature foals with related orthopedic issues such as incomplete ossification may fail to fulfill their intended athletic purpose, particularly in Thoroughbred racing. In humans, premature birth is associated with shorter stature at maturity and variations in anatomical ratios, linked to alterations in metabolism and timing of physeal closure in the long bones.

The long-term effects of gestational immaturity in the premature (defined as < 320 days gestation) and dysmature (normal term but showing some signs of prematurity) foal have not been thoroughly investigated. Studies have reported that a high percentage of gestationally immature foals with related orthopedic issues such as incomplete ossification may fail to fulfill their intended athletic purpose, particularly in Thoroughbred racing. In humans, premature birth is associated with shorter stature at maturity and variations in anatomical ratios, linked to alterations in metabolism and timing of physeal closure in the long bones.

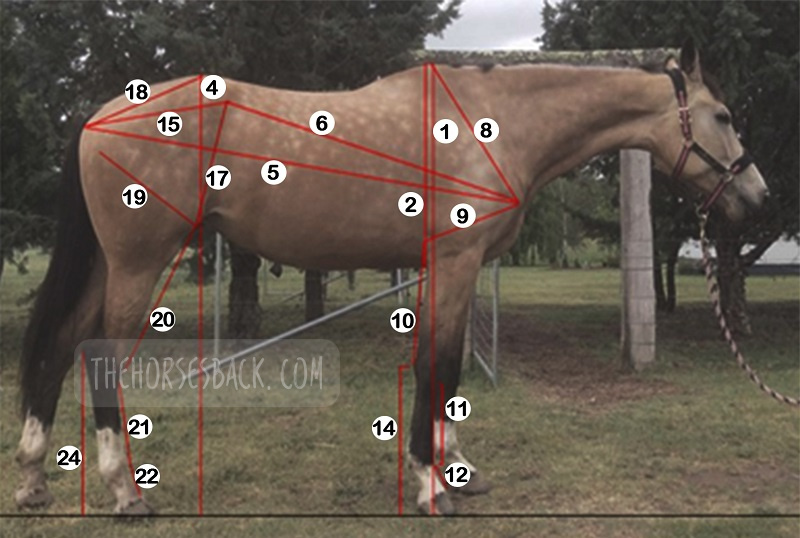

We hypothesized that gestational immaturity in horses might similarly be associated with reduced height and different anatomical ratios at maturity. In this preliminary study, the skeletal ratios of horses with a history of gestational immaturity, identified through veterinary and breeder records, were compared with those of unaffected, closely related horses (i.e., sire, dam, sibling).

External measurements were taken from conformation photographs of cases (n = 19) and related horses (n = 28), and these were then combined into indices to evaluate and compare metric properties of conformation. A principal component analysis showed that the first two principal components account for 43.8% of the total conformational variation of the horses’ external features, separating horses with a rectangular conformation (body length > height at the withers), from those that are more square (body length = height at the withers). Varimax rotation of PC1 and analysis of different gestational groups showed a significant effect of gestational immaturity (P = .001), with the premature group being more affected than the dysmature group (P = .009, P = .012). Mean values for the four dominant indices showed that these groups have significantly lower distal limb to body length relationships than controls. The observed differences suggest that gestational immaturity may affect anatomical ratios at maturity, which, in combination with orthopedic issues arising from incomplete ossification, may have a further impact on long-term athletic potential.

The paper can be accessed here.

Clothier J, Small A, Hinch G, Brown WY. Prematurity and Dysmaturity Are Associated With Reduced Height and Shorter Distal Limb Length in Horses. J Equine Vet Sci. 2020 Aug;91:103129. doi: 10.1016/j.jevs.2020.103129. Epub 2020 May 22. PMID: 32684267.

Perinatal Stress in Immature Foals May Lead to Subclinical Adrenocortical Dysregulation in Adult Horses: Pilot Study

Journal of Equine Veterinary Science

Abstract

The persistent endocrinological effects of perinatal stress due to gestational immaturity in horses are unknown, although effects have been reported in other livestock species. This pilot study tested the hypothesis that persistent adrenocortical dysregulation is present in horses that were gestationally immature at birth by assessing the salivary cortisol response to exogenous ACTH.Case horses (n = 10) were recruited with histories of gestation length < 315 d or dysmaturity observable through neonatal signs. Positive controls (n = 7) and negative controls (n = 5) were recruited where possible from related horses at the same locations.

The persistent endocrinological effects of perinatal stress due to gestational immaturity in horses are unknown, although effects have been reported in other livestock species. This pilot study tested the hypothesis that persistent adrenocortical dysregulation is present in horses that were gestationally immature at birth by assessing the salivary cortisol response to exogenous ACTH.Case horses (n = 10) were recruited with histories of gestation length < 315 d or dysmaturity observable through neonatal signs. Positive controls (n = 7) and negative controls (n = 5) were recruited where possible from related horses at the same locations.

The paper can be accessed here.

It’s an under-researched area, but I made some headway. Last year I was awarded my PhD for

It’s an under-researched area, but I made some headway. Last year I was awarded my PhD for

There’s more – a lot more. This is part of what’s known as Developmental Programming, or the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD).

There’s more – a lot more. This is part of what’s known as Developmental Programming, or the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD). There’s a wide range of possible problems – some horses have some of them, other horses have others, and some have none at all. They’re individuals, while everything else in their experience and care makes a difference too.

There’s a wide range of possible problems – some horses have some of them, other horses have others, and some have none at all. They’re individuals, while everything else in their experience and care makes a difference too.

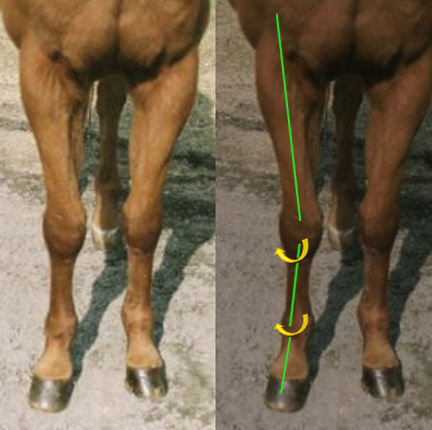

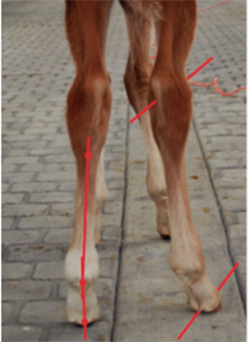

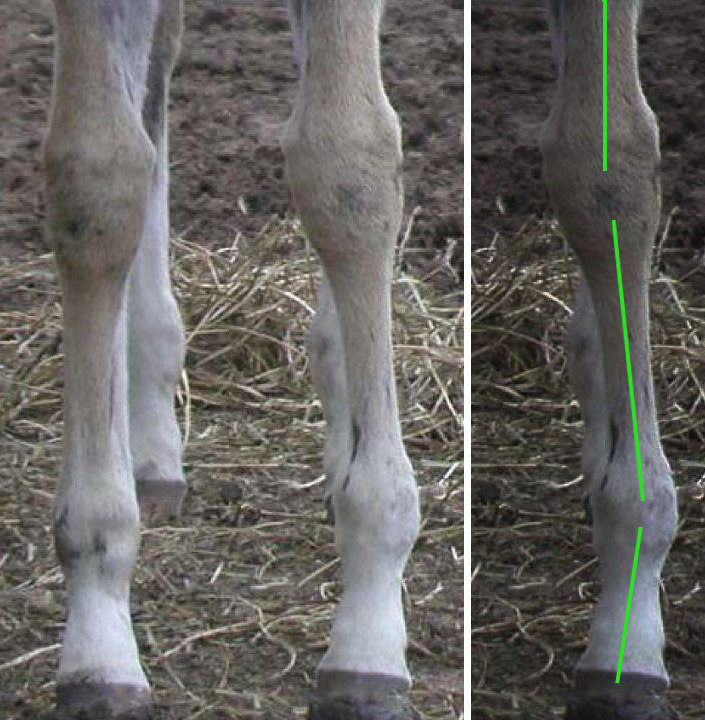

What we’re looking at is a combination of ALDs: carpal valgus and varus in front, and/or a tarsal valgus and varus behind.

What we’re looking at is a combination of ALDs: carpal valgus and varus in front, and/or a tarsal valgus and varus behind.