Less than 12 months ago, I wrote about neck threadworms and how they might be behind many horses’ frantic itching. The uptake on that article continues to astonish me. It has now had well over 60,000 visitors from all over the world and is still climbing steadily.

All text (c) Jane Clothier, https://thehorsesback.com No reproduction without permission. Thanks!

Itchy horses, it seems, are a perennial worry for thousands if not hundreds of thousands of horse owners (that’s counting the many who haven’t read the article).

At time of writing, it’s Spring in the northern hemisphere, and the reader numbers are building up again. So are the microfilariae levels.

The itchy horses are starting to scratch.

And the more I think about the neck threadworm issue, and read comments under the articles, the more I’m scratching my head.

[Article continues after advert.]

Who am I to write about Neck Threadworms?

Unsurprisingly, there have been a few knock-backs as well. I’m not a vet and, although I read as many papers as possible and discuss my thoughts with research vets before I post my blog articles, my assertions, which are based on observations and backed up with research, have still tickled the inside of a few noses.

To be honest, neck threadworms aren’t exactly an easy subject. Filarial nematode parasites are a complex life form so fundamentally different to those within our normal understanding. They rely on more than one host and undergo several stages in their development – they make the caterpillar to butterfly transformation look unambitious. (What, just two life stages? Onchocerca Cervicalis (neck threadworms) has twice that...)

And we are looking at not two, but three species here. The horse, the neck threadworms, and the biting midge (culicoid fly) that does the middle man part. The microfilariae leave the horse, courtesy of the midge, get flown around, travel through the midge’s body parts and enter different larval stages, and are then returned to the horse when the midge returns to ingest blood.

A lot of people are confused, and I don’t mean just horse owners. There are vets working for manufacturers of worming products who swear that their product can bump off the adult neck threadworms.

This would be welcome news to the World Health Organization, I’m sure, as decades of research have yet to find a chemical that successfully infiltrates the central nervous system of the adult Onchocerca Volvulus (the human version of the parasite, which currently affects an estimated 18 million people throughout Africa, Latin America and the Yemen) and eliminates it.

Moving on…

1. About standard texts on neck threadworms

“Oh, but those are the wrong signs for neck threadworms.” After “we don’t have that problem around here”, a lot of people are hearing this line when asking for professional help with their itchy horse. The problem, apparently, is that their horses don’t have the ‘typical’ itching along the ventral line, ie, the underside of the neck and belly.

I do wish that instead of saying, “it can’t be that, as it’s not described that way in the textbooks”, more people would wonder instead if there were something that could be added to those textbooks.

Textbooks tend to be based on research that other people have done. In the case of neck threadworms, there is relatively little out there. This means that a lot of information that finds its way into books and training is already reasonably dated, and not exactly far ranging.

Here’s how to put together a program of treatment for your horse with neck threadworms (and maybe the Itch) – How to Fight the Big Fight Against Neck Threadworms

2. Neck threadworms may be the same worldwide, but biting midges aren’t

This is something we’re especially aware of here in Australia, where geographical isolation has led to the evolution of some remarkable indigenous species, found nowhere else in the world. Our ticks are different. Our flies are different. We have marsupials.

Most of the research on neck threadworms hails from the US. When findings of research involving vectors – the biting midge ‘middle man’ – are applied worldwide, it’s important to remember that some conditions can be ‘similar but different’.

Indeed, when we look at research on Onchocerca Volvulus, neck threadworms’ well-studied cousin that affects humans, we can come across statements like this one: “Many simuliid species have been incriminated to a greater or lesser degree in the transmission of O. volvulus, their relative vectorial roles contributing to shape diverse transmission patterns across endemic areas.” (Basáñez M-G et al, 2006.)

Say what? Different flies are active in different areas and create different patterns of transmission? I think the point is made well enough.

[Article continues after advert.]

3. The biting midges must be studied too

If we consider the possibility of different culicoides acting as vectors, then other differences come into consideration as well.

European studies into Sweet Itch (Summer Itch, Queensland Itch) have shown that different types of biting midge have a preference for different parts of the horse’s body.

What? But that’s breaking the rules, surely? Yup. That’s what nature does – makes its own rules.

4. More rule breaking

It doesn’t stop there: studies of cattle in Darwin (a hotbed for livestock research due to its tropical climate) have revealed the presence of more than one type of Onchocerca, with at least two species of the parasite being found in the ‘wrong’ animal.

This suggests that one or more species of biting midge are ‘cross-contaminating’ the parasite by moving from one species of mammal to another. Possibly. But the point here is that variation exists – we can’t assume that because a few studies have identified certain conditions, these are replicated globally.

5. Neck threadworm life cycle: what happens and when

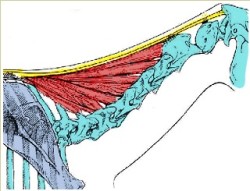

Another point that isn’t clearly answered by existing research is how much the microfilariae travel. If the adult worms are living in the nuchal ligament, that is where they give birth to zillions of microfilariae. Some flies must bite in this area in order to ingest the microfilariae and take off with them. It then follows that there are millions that don’t get ingested, and die off. It’s the die off that causes the itching, both during normal times and after treatment with ivermectin.

So here we have itching that’s not on the ventral midline.

It’s more remarkable that horses do itch on the ventral midline. If adults live in the nuchal ligament, mostly, and microfilariae are dying on the ventral line, either the microfilariae are traveling long distance, subcutaneously, or there are adults living in the ‘white line’ that runs from the the sternum to the umbilical area.

At the very least, we can say that this is problem isn’t confined to the underside of the horse.

If your horse has the Itch, Queensland Itch, Sweet Itch, Summer Itch, Summer Sores… sometimes it’s really neck threadworms. Read the original article, The Disturbing Truth About Neck Threadworms and Your Itchy Horse

6. And look at the behavior of itchy horses

Whatever the country, whatever the culicoid species, the horse that’s going insane with itchiness can only ever scratch the parts that it can reach. Most horses can easily scratch their toplines on branches and fences, whereas far fewer are seen scratching their bellies on the ground. Horses will always break the skin in any area that they scratch in earnest, and consequently the blood attracts the biting midges to that area.

As the immune system goes into stratospheric hypersensitivity, intense itching can become an all-over sensation. Remember having chicken pox, or measles? Or ask any person who has such an uncontrollable immune response.

Let’s not overlook the possibility that horses displaying lesions on their undersides are in the more advanced stages of parasitic infestation, or are rugged (fewer areas are available for the midges to bite), or even – taking the earlier points on board – that they live in areas where local midges prefer that part of the horse’s body.

7. And let’s not forget owner behavior

Who is that calls the vet, and why? Not the horse… An owner who notices their horse scratching its mane and tail head is way less likely to contact a vet than the owner who sees bald, scratched patches on their horse’s underside.

It’s the difference between “dang, my horse has the itch” and “what the heck’s my horse doing, rubbing under there?”

It entirely makes sense that the more advanced cases, with all over itching and rubbed patches, are more likely to be seen by vets, and to make it into veterinary research. (Note: in research, not all horses whose nuchal ligaments were dissected at necropsy displayed ventral lesions, far from it, although many tested positive for Onchocerca Cervicalis.)

[Article continues after advert.]

Where to next, with neck threadworms?

Well, what do you think? I know what I think. I know what I’ve experienced with my horse.

I trust my observations. I trust the research that I’ve read and that fits closely with my observations. And no, I’m not cherry-picking research to prop up my own emotionally driven ideas.

At present, other explanations aren’t available, but lots of questions remain. Looking at the ones here, it’s easy to understand why research is such a long and painstaking process – it’s not possible to go from A to Z or even A to D without covering the intervening steps.

For the horse owner, just one thing is clear, and that is that we have a horse being driven mad by itching. So, please do stick with ivermectin for identifying the initial reactions. Stick with ivermectin or moxidectin/praziquantel wormers for reducing the problem (moxidectin will not cause the itching response post-worming).

And remember, that not every itchy horse has neck threadworms.

© All text copyright of the author, Jane Clothier, www.thehorsesback.com. No reproduction of partial or entire text without permission. Sharing the link back to this page is fine. Please contact me for more information. Thank you!

Questions, thoughts or comments? Join us at The Horse’s Back Facebook group.

Reference

Basáñez M-G, Pion SDS, Churcher TS, Breitling LP, Little MP, et al. (2006) River Blindness: A Success Story under Threat? PLoS Med 3(9): e371. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0030371