Look on any ivermectin or moxidectin-based wormer packet and you’ll see a long list of parasites. Tucked in neatly at the end – it’s nearly always at the end – you’ll see the words Onchocerca cervicalis, otherwise known as neck threadworms.

Also known as neck threadworms, these critters vary in length from 6cm to 30cm (think the length of a regular ruler). Astonishingly, they live in the horse’s nuchal ligament.

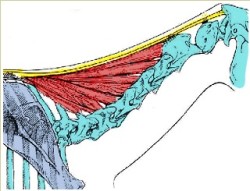

Yes, the nuchal ligament. It runs the full length of the neck, from poll to withers, with a flat ligament part connecting with the cervical vertebrae.

Apparently, most horses have Onchocerca. For many they’re not a problem, but some horses develop a reaction to their microscopic larvae (the microfilariae). This is known as Onchocerciasis. The horses become itchy, mostly around the head, neck, chest, shoulders and underside of the belly. That’s why owners often make the understandable assumption that their horse has Queensland itch or sweet itch.

A quick introduction to neck threadworms

Original article by Jane Clothier, posted on https://thehorsesback.com, June 2013. All text and photographs (c) Jane Clothier. No reproduction without permission. Links to this page are fine.

Onchocerca is what’s known as a parasitic filarial worm (nematode). One reason these worms get relatively little attention is that they never live in the intestines. The microscopic larval form live in the horse’s skin, mostly around the head, neck, shoulders, chest and underside of the belly. It is the adult worm that later makes its home in the nuchal ligament.

The problem is global and horses in most countries have been found to have this parasite. Unfortunately for those of us who keep horses in warmer, humid climates, it’s more frequent here. The biting insect that serves as a carrier is the Culicoides fly, which is also connected to Queensland Itch (aka Sweet Itch, Summer Itch, etc.).

It’s an unfortunate coincidence of environment that leads to many cases of neck threadworms being missed, because they’re assumed to be Itch.

Does your horse have “the itch” – or neck threadworms?

It’s a humdinger of a thought. If your horse is itchy, something different could be happening to what you think is happening.

- Your horse has the ‘regular’ itch (ie, Queensland, sweet, whatever it’s called in your region) and are reacting to midge spit – and nothing else. (The point of this article certainly isn’t to try and say that all itch cases are due to neck threadworms. Just some.)

- Your horse has neck threadworms and its inflammatory reaction to them has increased its sensitivity, so it’s now reacting to fly bites everywhere – in other words, Queensland/sweet itch has been triggered as a secondary response.

- Your horse only has neck threadworms, in which case they’re probably rubbing along the mane and particularly the base of mane, around the neck and face, under the chest and down the ventral line (under the belly), but not on the tail head – or at least, relatively little.

Are you by any chance now thinking other horses you know? If so, they might be suffering from Onchocerciasis. There’s a lot of it about.

So how do we identify neck threadworms?

Neck threadworms have a distinctive life cycle, but as is so often the case, the problem presents in different ways, depending on the individual.

In my brumby Colo, it started with him scratching the underside of his neck on posts. That was about 3 months before I had an inkling it might be neck threadworms. How I wish I’d known what it was at that point, so that I could have nipped the problem in the bud…

I’ve also seen it manifest as a new, previously unseen itchy and scurfy patch on the lower part of the neck of a horse who’d never been itchy. And I’ve heard of a local horse who suddenly started furiously itching his face, bang in the middle of the forehead, to the point that it bled. He had never been itchy before.

These are the classic early signs, usually recognised by the owner only through miserable hindsight. Other signs include small lumps forming along the underside of the horse and on its neck and face, weeping spots, and a scaly crest to an area of the mane through rubbing.

The base of the mane, just in front of the withers, seems to be party central where neck threadworms are concerned.

The real nastiness of neck threadworms

It just gets better: the larvae can travel to the horse’s eyes, where they can cause untold damage. This cheering sentence from Scott and Miller’s Equine Dermatology sums it up: “O. cervicalis microfilariae may also invade ocular tissues, where they may be associated with keratitis, uveitis, peripapillary choroidal sclerosis, and vitiligo of the bulbar conjunctiva of the lateral limbus.”

Oh heck. Nobody’s sure how common this is. All I know is that I don’t want to find out the hard way.

Consider this: in humans, a slightly different strain of Onchocerca infestation is known as River Blindness.

Please remember this detail when you’re deciding whether to worm for neck threadworms or not.

The very strange lifecycle of the neck threadworm

These worms have a complicated existence. They’re among the shapeshifters of the parasitic worm world, developing through several larval stages before reaching adulthood.

The first stage microfilariae live in the horse, close to the skin. Their numbers are highest in the spring and decrease to their lowest point in mid-winter. They live in clusters, which is why you may first notice patches of scurfy skin where the horse has started itching. This is a reaction to the dead or dying larvae.

At this point, our good friends the culicoid flies make a contribution, by biting the horse and ingesting a good number of microfilariae along with blood. Within the fly, the larvae then develop through a further stage (or two). They are then deposited back into a horse when the flies bite. The flies can do this for an impressive 20 to 25 days after first hoovering up the larvae.

Back in a host horse, the larvae then make their way via the bloodstream to the connective tissue of the nuchal ligament, which runs along the crest of the neck. Here they moult and develop into adult worms. The adults live for around 10 years and in this time, the females release thousands of microfilariae (larvae) very year.

Original article by Jane Clothier, posted on www.thehorsesback.com, June 2013. All text and photographs (c) Jane Clothier. No reproduction without permission, sorry. Links to this page are fine.

No matter where the adult worms settle, the itchiness is caused by the microfilariae that aren’t lucky enough to be consumed by a fly and are instead left to die off.

The next part’s really not fair. The more the horse itches and breaks the skin, the more the flies will bite exactly where the microfilariae are located, before transporting them to the same or another horse, to start all over again.

Unsurprisingly, horses with most lesions have higher microfilariae counts – it’s a perfect ascending spiral of parasite-induced discomfort.

The Onchecerca life cycle lasts for 4 to 5 months.

Can we test for neck threadworms?

The microfilariae can be identified in the living horse through a biopsy of the nuchal ligament. Published veterinary research shows you won’t get any indication within 34 days of worming, so the timing is critical.

A dose of ivermectin-based wormer is the quickest way to tell if your horse has them. If the microfilariae are present, the horse usually responds with intense itching – and I mean, manically intense, demented itching – around 48 to 72 hours after worming.

It may develop weeping, gunky spots at the base of the mane. (If you live in a paralysis tick area, it’s similar to the localised reaction you see in response to the ticks.) These are very specific spots around 1cm in diameter, with hair loss after they’ve erupted.

My brumby responded this way, rolling furiously and rubbing vigorously against posts. Unsurprisingly, he was also hard to handle for a few days. He was definitely sore at the base of the neck, where the weeping eruptions came out, and didn’t want to be touched there. I have to say that the scale of his reaction came as a shock to me, so take heed and be prepared with some soothing salves.

What can we do about adult neck threadworms?

Here’s the depressing answer: not much. But we can manage them.

The adults live for 10-12 years and happily inhabit the nuchal ligament. What often happens is that the horse’s body throws down calcification around the adult worms in an attempt to isolate the foreign body. In some horses, you can feel a collection of pea-like bumps in the nuchal ligament. In the ones that I’ve checked, this was just in front of the withers.

The slightly better news it that the worms are so fine and the lumps so small that it doesn’t seem to affect the function of the ligament, which is tough and fundamentally taut anyway. However, I’ve not yet knowingly seen a horse with a long history of neck threadworms – I’d be interested in doing so.

Heavier calcification is usually most prevalent in horses in their late teens. It figures, as the adult wormers are older, and longer. Apparently they intertwine and live in small clumps. Mid-aged horses have mainly shown inflamed tissue around live parasites.

In horses less than 5yo, the parasites can be present but there’s relatively little immunological response. So if your horse has suddenly developed itchiness at the age of 5 or 6, you could be looking at the presence of this parasite.

Original article by Jane Clothier, posted on www.thehorsesback.com, June 2013. All text and photographs (c) Jane Clothier. No reproduction without permission, sorry. Links to this page are fine.

Managing the initial outbreak

Do you worm your horses? Do you want to reduce the itching at the cost of having to worm more? I know I do, but I realise that some people can’t abide the thought of chemical wormers, or their increased use. But here’s what you can do if you want to reduce that dreadful itching and virtually eliminate the possibility of eye damage.

Unfortunately, there’s no single recommended protocol for worming against neck threadworms, so you’re in fairly uncharted territory.

To address the initial outbreak, the advice ‘out in the field’ is to use a regular dosage of an ivermectin-based wormer, multiple times until symptoms subside. The recommended interval I’ve seen is a week, but do check with your *equine* vet first.

To address the initial outbreak, the advice ‘out in the field’ is to use a regular dosage of an ivermectin-based wormer, multiple times until symptoms subside. The recommended interval I’ve seen is a week, but do check with your *equine* vet first.

- I’ve also read forum posts by US horse owners stating that a double dosage at fortnightly intervals is the most effective treatment. It’s usually around three doses, or until symptoms subside. One reason is that lower doses do not kill off enough larvae, allowing resistance to develop amongst those that remain. Wormers are certainly tested as safe at higher dosages, but again, horses are individuals, so always check with your *equine* vet first.

- I’ve read that an injection of ivermectin can be more effective, with off-label use of a product such as Dectomax being recommended as the heavy artillery when all else has failed. Again, do check with your *equine* vet.

Some say that an ivermectin and praziquantel wormer is more effective. One small comfort is that these wormers are available in the lower price ranges. It’s a consideration, because if you’re worming multiple horses, this won’t be a cheap time. It may even be worth looking at the large bottles of liquid wormer used by studs for greater economy.

Published research has shown that moxidectin-based wormers are equally as effective in addressing the microfilariae (but don’t double-dose with this one – only with ivermectin).

Whichever option you follow, it’s worth following this worming protocol with prebiotics, probiotics and ‘buffers’ such as aloe vera to support a healthy gut lining.

Reducing the larval population

After the initial worming, it’s a matter of management. What you’re trying to do is keep the numbers of microfilaraie low, so that the horse’s itching is reduced. Remember, most horses show little reaction, although the parasites are present. The aim has to be to bring them down to levels the horses’ systems can deal with, while taking other measures to boost the horses’ immune system.

- Some vets say a single dose every 6-8 weeks during the fly season.

- Others say every 3 months, timed in accordance with the larval lifecycle, which is 4 to 5 months.

- In humid sub-tropical zones, where all parasite burdens are dramatically higher, I’ve heard of people doing it as frequently as once a month.

Beyond that, you’re back to the barrier treatments – fly rugs, lotions and potions to deflect the flies and to insulate the skin, lotions to soften the skin and heal the lesions, fly screens on shelters during the day, etc. And don’t forget about boosting your horse’s immune system generally through sound nutritional approaches.

And if we do nothing?

If we don’t address the problem one way or another, we have very itchy horses, for their entire lives.

Researchers say that the calcification in the ligaments has no effect, but you’ve got to wonder. There’s no guarantee that those scientists had a highly developed understanding of equine biomechanics. Maybe they did, but… who knows. A lot of the small amount of research available is over 20 years old and the knowledge base has since grown.

There’s a small but serious risk of damage to the eyes.

On the plus side, Onchocerciasis hasn’t been found to have any association with fistulous withers.

How to put together a program of treatment for your horse with neck threadworms (and maybe the Itch) – How to Fight the Big Fight against Neck Threadworms

To recap…

Onchocerciasis is so often masked by the itch that awareness, even in the regions where it’s rife, is low.

And in those same regions, there are so many highly prevalent and deadly parasites – the worms that cause colic, that drag down the horse’s condition, that can kill through spontaneous mass emergence from encysted larval stages – that the neck threadworm larvae simply doesn’t get much of a look-in.

To repeat, I’m not saying that all cases of itch are neck threadworms. Just that these parasites may be involved and can be a contributory factor in a heightened immunological response that leads to Queensland itch (or sweet itch, or whatever you know it as).

However, some horses definitely have neck threadworms. The earlier we can identify and manage it, the better.

We can’t eliminate the neck threadworms, but we can certainly manage the effects and make our horses’ lives more comfortable.

(c) Jane Clothier – no reproduction without permission – jane@thehorsesback.com

Here are some of the links I’ve been accessing for this article.

Equine Onchocerciasis: Lesions in the Nuchal Ligament of Midwestern US Horses. G. M. Schmidt, J. D. Krehbiel, S. C. Coley and R. W. Leid. Vet Pathol 1982 19: 16.

Efficacy of ivermectin against Onchocerca cervicalis microfilarial dermatitis in horses. Herd RP, Donham JC, Am J Vet Res. 1983 Jun;44(6):1102-5. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6688162

Onchocerciasis, Submitted by EquiMed Staff. http://equimed.com/diseases-and-conditions/reference/onchocerciasis

Onchocerciasis, the Neck Thread Worms and Midline Dermatitis in Horses.

The Hypersensitivity of Horses to Culicoides Bites in British Columbia. Gail S. Anderson, Peter Belton and Nicholas Kleider. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1680856/pdf/canvetj00574-0044.pdf

Onchocerca in Horses from Western Canada and the Northwestern United States: An Abattoir Survey of the Prevalence of Infection, L Polley. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1790494/

Research of skin microfilariae on 160 horses from Poland, France and Spain. M.T. FRANCK et al. Am J Vet Res. 1983 Jun;44(6):1102-5. http://www.revmedvet.com/2006/RMV157_323_325.pdf

Efficacy of ivermectin against Onchocerca cervicalis microfilarial dermatitis in horses. Herd RP, Donham JC. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6688162

Equine Dermatology. By Danny W. Scott, William H. Miller Jr. via Google Books [link now unavailable]

Baba Yaga’s Mirror. Personal blog. [link now unavailable]