In this guest post, Dr. Sonja Dominik describes equine dwarfism and what the latest tests mean for horse breeders. Sonja is a Research Scientist in Quantitative Genetics at CSIRO, Australia’s national science agency.

In this guest post, Dr. Sonja Dominik describes equine dwarfism and what the latest tests mean for horse breeders. Sonja is a Research Scientist in Quantitative Genetics at CSIRO, Australia’s national science agency.

She is currently a Superstar of STEM, appointed by Science & Technology Australia to increase the public visibility of women in science. To top that off, she was also a competitor in the 2018 series of Australian Ninja Warrior.

Sonja writes :

There’s small and then there’s very small.

There’s cute – and then there’s dwarfism, which isn’t cute at all.

Equine dwarfism is a very complex genetic condition. However, a few facts apply to all dwarf types in horses.

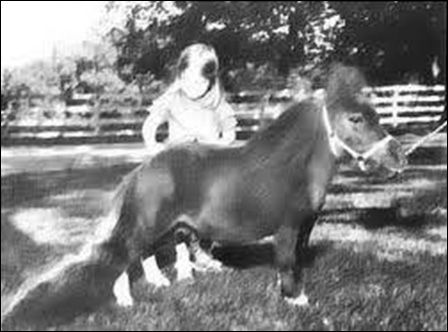

First, dwarfism in horses is caused by a disruption of the structural processes in bone and / or ligament development. It can potentially occur in any horse breed, but is most prevalent in Miniature horses, Shetland ponies and Friesians, but has also been described in Mustangs and donkeys.

All characterized dwarf types in horses are disproportional, meaning that only some parts of their bodies – eg. their limbs – are reduced in size.

Dwarfs can suffer secondary conditions, usually due to their skeletal deformations, and multiple health problems, such as metabolic, digestive or respiratory disorders.

In genetic terms, dwarfism is a recessive condition (more on that below). Not all dwarf types are genetically characterized, but genetics tests are available for some.

Horses with dwarfism aren’t just tiny

Four types of equine dwarfism have been defined, based on their physical characteristics. However, there are a lot of overlaps and there are dwarf horses that are difficult to fit into any of the described types.

1. Short legs, long bodies.

Achondroplasia is the most common form of dwarfism. Affected horses have short-limbs with a normal trunk, although often with an elongated back.

The term achondroplasia actually means ‘without cartilage formation’, although that is not quite correct…. these dwarfs have cartilage, but the problem is that cartilage is not turned into bone while they are gestating.

However, this type of dwarf can lead a relatively normal life.

2. Large heads, distorted features.

Brachycephalic dwarfs have a bulging forehead, with a short and flat nasal bridge, overly large eyes, and nostrils that are higher than what is considered normal.

They also have a short neck and limbs, and often have spine deformations. This type of dwarf often has a shortened life span.

3. Multiple deformities.

Diastrophic dwarfs can have twisted limbs and / or multiple limb deformities and other characteristics such as a domed head and roached back and a pot belly.

Due to the severely deformed limbs, affected animals would require splints or surgery to move properly.

4. No bone.

Hypochondrogenesis is the most severe condition of dwarfism where the bones are not ossified at all. Affected fetuses are normally aborted before birth.

Here’s what we know about dwarfism genetics

Recently, a genetic test for dwarfism in miniature horses was developed at the Gluck Equine Research Center, University of Kentucky.

This tests for achondroplasia-like dwarfism, which is caused by mutations in the so-called ACAN gene.

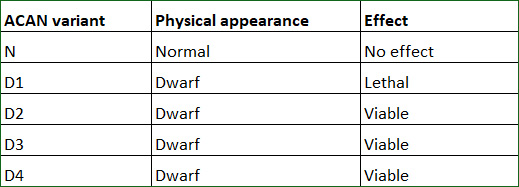

Every horse carries the ACAN gene, which encodes the protein Aggrecan, an integral part of the extracellular matrix in cartilaginous tissue. Four variants of the gene have been identified that cause the above types of dwarfism – there might be even more.

What does a genetic test tell us?

Every horse inherits two copies of the genetic code, one from each parent. This is really important in our understanding of dwarfism and genetic test results, because all known dwarfism types are recessive conditions.

What this means is that only horses carrying two copies of affected genes, ie. one from each parent, will actually be dwarfs. Horses with one affected and one unaffected gene will be a carriers.

Carriers are normal in appearance, but there is a 50% chance that they will pass the affected copy of the gene on to their offspring. This means that if two carriers are bred, there is a 25% chance that the offspring is affected by dwarfism.

And there’s a second gene too

As well as ACAN, another gene has been identified that causes dwarfism if it is mutated. This gene is B4GALT7, which, if mutated, leads to disrupted bone and cartilage formation. (In humans is associated with Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, a group of connective tissue disorders.)

This mutation is prevalent in the Friesian breed – affected horses have also short limbs, deformation of the rib cage, and hyperextension of the fetlock joint5.

Dwarfism in the Friesian horse is also recessive and again, only horses with two copies of affected genes are dwarfs.

Why is dwarfism only present in certain breeds?

There are a number of possibilities.

- Selective breeding may have played its part: horses with favorable features have sometimes been carriers of a defective version of a gene.

- A single copy of the defective gene might have had a favorable effect on small size, so animals with a single copy might have been preferentially selected.

- However, as size in horses is influenced by a large number of genes, the defective version of the genes might be linked to versions of other genes that cause small size. It could have “hitchhiked” during the selection for small stature.

In this way, selection for smaller stature, obviously without genetic testing, has led to a higher frequency of the defect gene in the Miniature horse population.1

It is less clear which favorable feature might have been selected for in the Friesian horse, although we do know that the stallions Paulus 121 (b.1913) and Us Heit 126 (b.1917) each sired 7 dwarf foals.

What is skeletal atavism?

Skeletal atavism has similar physical features to dwarfism, with horses being deformed and with shortened limbs. It also occurs in Miniature horse and Shetland ponies.

The characteristics include abnormal bone growth, which is evident in the upper limb bones, including the ulna in the forelimb and the fibula in the hindlimb.1

In atavistic horses, the ulna extends from the humeroradial to the carpal joint (ie. elbow to knee) and the fibula from the femerotibial to the tarsal joint (ie. stifle to hock).6

This can cause splayed legs and create movement difficulties.6

Atavistic characteristics have been observed in fossil records of earlier ancestors of a species, and have then reappeared quite recently.4 The earliest report in recent times was in Shetland ponies in 1958.7

Genetically speaking, these are not new mutations, but are ones that became dormant, only recently being re-expressed.2

Like dwarfism, atavism is a recessive condition, which means that affected horses need to have inherited an affected copy of the gene defect from each parent.

How can we avoid dwarfism?

The occurrence of dwarf horses is a matter of chance, but the fewer horses in a population that carry the affected genes, the lower the chances that two carrier horses will be bred and produce a dwarf foal.

To avoid dwarfism and reduce the frequency of affected genes in a population, carriers of affected genes should not be bred.

How do we know that a horse is a carrier?

There are only two ways to know if a horse is a carrier:

1. If the horse ever had a dwarf foal, it is clearly a carrier.

2. Genetic testing.

In North America, you can test for dwarfism in Friesians here and for dwarfism in miniature horses here.

What tests are available?

Genetic tests to identify carriers of the variants that cause dwarf appearance are now available for dwarfism in Miniature horses and Friesian horses, and for skeletal atavism in Shetland ponies.

Genetic testing is straight forward. All that is required is a sample of hairs, including hair bulbs, that is sent to a testing laboratory and the test will establish if the sample originates from a carrier of defect genes that cause dwarfism.

If a test is positive, it can be devastating. However, if your horse is a carrier and is only bred with horses that are also tested and shown to be unaffected non-carriers, all offspring will be unaffected.

However, the defect gene will still be passed on to the offspring, with a 50% chance to create a new carrier and dwarfism gene remains in the population.

That means you’re depending on future owners to do the right thing – and they very well may not do so.

Finally, here’s how different versions of the ACAN gene affect the horse (adapted from Eberth et al. 2018)

If you love horses and love your breed, then the truly responsible option is to test every horse you breed from. If you then breed and sell a mare or entire horse colt that’s a carrier, it remains that someone less responsible than yourself may then breed it to an untested stallion.

If you’ve enjoyed Sonja’s writing, do take a look at another of her public posts on The Conversation’s blog, about the giant cow Knickers – yes, THAT giant cow. Read her article: Yes, Knickers the steer is really, really big. But he’s far short of true genetic freak status

References:

- I.J.M. Boegheim, P.A.J. Leegwater, H.A. van Lith, W.Back (2017) Current insights into the molecular genetic basis of dwarfism in livestock. The Veterinary Journal 224: 64.

- J.M.Cantu, C. Ruiz (1985) On atavisms and atavistic genes. Ann Genet 28: 141.

- J.E. Eberth, K.T. Graves, J.N. McLeod (2018) Multiple alleles of ACAN associated with chondrodysplastic dwarfism in Miniature horses. Animal Genetics 49: 413.

- B.K. Hall (1995) Atavisms and atavistic mutations. Nature Genetics 10: 126.

- P.A. Leegwater, M. Vos-Loohuis, B.J. Ducro, I.J. Boegheim, F.G. van Steenbeek, I.J. Nijman, G.R. Monroe, J.W.M. Bastiaansen, B.W. Dibbits, L.H. van de Goor, I. Hellinga, W. Back, A. Schurink (2016) Dwarfism with joint laxity in Friesian horses is associated with a splice site mutation in B4GALT7. BMC Genomics 17:839

- Rafati, L.S. Andersson, S. Mikko, C. Feng, T. Raudsepp, J. Pettersson, J. Janecka, O. Wattle, A. Ameur, G. Thyreen, J. Eberth, J. Huddleston, M. Malig, E. Bailey, E.E. Eichler, G. Dalin, B. Chowdary, L. Andersson, G. Lindgren, C.-J. Rubin (2016) Large Deletions at the SHOX Locus in the Pseudoautosomal Region Are Associated with Skeletal Atavism in Shetland Ponies. G3 Genes Genomes Genetics 6: 2213.

- Tyson, J.P. Graham, P.T. Colahan, C.R.Berry (2004) Skeletal Atavism in a Miniature Horse. Veterinary Radiology and Ultrasound 45 (4): 315

Links:

https://thehorse.com/18222/12-miniature-horse-health-risks

https://www.ofhorse.com/view-post/Equine-Dwarfism-Not-a-Desireable-Trait,

http://www.littlemagicshoes.com/page5.html

https://www.vgl.ucdavis.edu/services/horse/Friesian.php

https://gluck.ca.uky.edu/sites/gluck.ca.uky.edu/files/2022-01/dwarfism_miniatures_submission_form_april_2017.pdf